Daniel Tong

My closest, most long-standing musical relationship is with Beethoven. The essential joy of life as an interpreter is, to me at least, in making friends with these extraordinary composers through their music; I know his moods, his rough humour, his tenderness and his anger. But above all, I remain in awe of his single-mindedness, both as man and artist, a perfectionism that never compromised either in artistic vision, or its absolute refinement and craftsmanship.

This relationship has been nurtured over a period of nearly forty years, since my childhood piano teacher gave me one of Beethoven’s Bagatelles when I was not yet in double figures. Captivated, I learned another, and then a third. It was around this age that my mum taped a recording of the Archduke Trio for me from a performance given by Cortot, Thibaut and Casals, broadcast on the radio. I was hooked, and played this tape again and again, until it finally gave up and broke.

As a teenager I was drawn to Beethoven’s most dramatic, stormy side, and played the Pathétique, Op. 13 and Appassionata, Op. 57. In the sixth form, I played the Pastoral, Op. 28 when I reached the piano final of the BBC Young Musicians competition, and the exquisite Sonata Quasi una Fantasia, Op. 27 No. 2 in my last recital at school. During the same period, I performed my first concerto with orchestra – Beethoven of course, No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 37 – and also began playing chamber music with his Spring Sonata, Op. 24 for Violin and Piano, and G Minor Sonata, Op. 5 No. 2 for Cello and Piano. At music conservatoire in London, hungry for more, I worked on two of the last Sonatas, Op. 109 and Op. 110, performing the latter in my final recital.

Fortepiano

And so it went on. And goes on.

As my relationship with Beethoven deepened, it resulted in a more personal way of interpreting his music. The reality, of course, is that no one can ‘know’ a composer’s music in the sense that they will reproduce it as the composer would have played it. This is why we can admire András Schiff, Arthur Schnabel, Ronald Brautigam and Alfred Brendel equally in this repertoire or, perhaps more enjoyably, disagree over whose performance most beguiles us. And with recordings of all thirty-two Beethoven Piano Sonatas by these icons and hundreds more, who needs another?

In 2015, Krysia Osostowicz and I decided to bring our cycle of Beethoven’s ten Violin Sonatas into the twenty-first century, by commissioning ten new pieces, one to partner each of them. The fascinating and inspiring results of this project can be heard on SOMM Recordings, Gramophone Magazine commenting that our performance was “hard to beat amongst contemporary versions”.

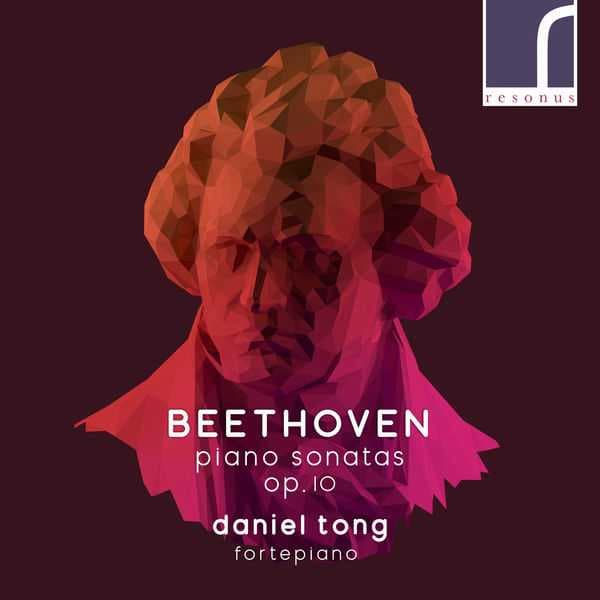

When cellist Robin Michael, a great friend with whom I had played the cello and piano works several times, approached me about a recording to celebrate Beethoven’s 250th anniversary in 2020, we also wanted our cycle to stand out from the crowd. We tried several fortepianos, either originals or modern copies, trying to find the right fit for my fingers and Robin’s gut-strung cello, finally alighting on a fabulous McNulty copy of an 1815 Walter instrument. This project was one of the most enlightening of my life, the results of which can be heard on Resonus Classics.

Beethoven: 12 Variations on “See the Conquering Hero Comes”, WoO 45: II. Variation I

“Michael and Tong take on this key repertory in a spirit of fresh, fearless égalité, stylistic certainty and all-round technical brilliance” (International Piano Magazine)

Beethoven: Sonata No. 1 in F Major, Op. 5 No. 1: II. Allegro

My relationship with this McNulty/Walter finally gave me the courage, at the age when Beethoven was beginning his late period, to finally record his Piano Sonatas, encouraged by the brilliant producer at Resonus Classics, Adam Binks. The McNulty is a superb instrument that really deserves to be heard in this repertoire, and seems to complement my interpretations ideally. Op. 10, with it’s combination of storm and drama (No. 1), wit and invention (No. 2) and symphonic grandeur, as well as confessional introspection (No. 3) seemed like the ideal place to start. The whole of the young Beethoven, but something heard a little less often than the Pathétique or Moonlight.

My first solo disc, recorded several years ago, was of music by Schubert, another composer with whom I feel a close affinity, despite his personality being very different to that of Beethoven. In this movement, the specific brand of poignant melancholy is something that perhaps only Schubert could touch.

Schubert: Piano Sonata No. 20 in A Major, D. 959: II. Andantino

The only issue with a project such as this is money! Good fortepianos are expensive to hire, and a fine technician must be on hand throughout the sessions to look after these sensitive instruments. I am immensely heartened by the generosity that has meant a really encouraging start to my Kickstarter campaign, but I still have nearly half the funds to find. All details, including rewards are here, and all pledges are hugely valued!

Daniel Tong is a pianist and teacher, founder of the Wye Valley Chamber Music Festival, pianist of the London Bridge Trio and Head of Piano in Chamber Music at the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire.

www.danieltong.com

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter