The name Johannes Brahms, born on 7 May 1833 in Hamburg, is generally known around the world. And while some of his melodies and compositions have gained international and popular currency, the psychological depths of his character have remained a mystery. He was a shy and awkward boy, and this awkwardness never entirely left him. On one hand, he was fantastically loyal and generous, but he could also be highly unpleasant, secretive, mean spirited, and full of irony and reserve. And let’s not forget his highly ambivalent, some would say, misogynist attitude towards women.

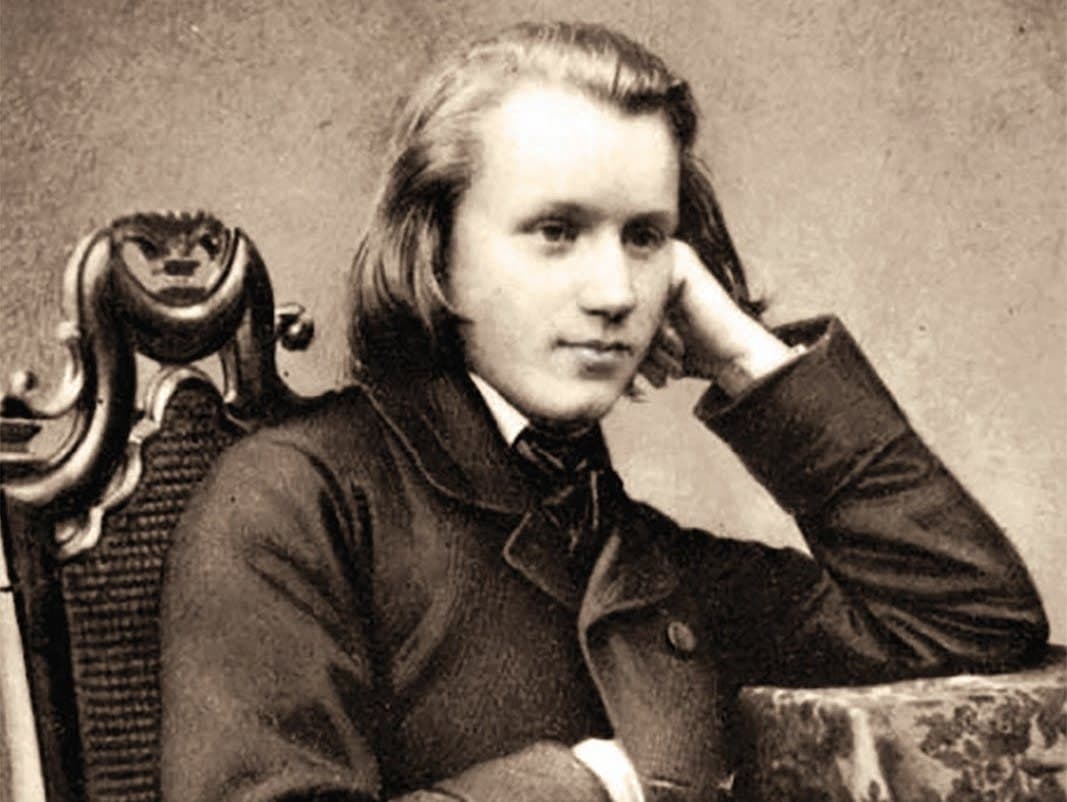

Johannes Brahms, 1853

His conflicted and often contradictory personality, however, found an anchor in his compositions. As a scholar writes, “Brahms deftly crouched his romantic, melodious, emotional music in the classical form, creating a protective boundary that contained the emotionalism of his compositions in an articulated form and structure.” When it came to music, Brahms was an uncompromising perfectionist, full of abrasive and closely guarded privacy. As the Brahms scholar Walter Frisch writes, “the kind of contentment and romanticized perfection that eluded him in his personal life found a clear and sublime outlet in his music.”

Johannes Brahms: Scherzo, Op. 4

Here and elsewhere, Brahms’ childhood has been described in much detail, but his musical life really started in earnest in 1853. Brahms was barely 20 when he visited the Rhineland and arrived unannounced at the Schumann residence. He did carry a letter of introduction from Joseph Joachim, but Schumann was not at home, and his eldest daughter Marie told him to come back the next day. When Brahms returned on 1 October 1853, Schumann was apparently still in his dressing gown, and after some awkward moments, Brahms sat down to play. Supposedly, Brahms played his first C-major Sonata, with its references to Beethoven’s “Hammerklavier” and “Waldstein” on the first page.

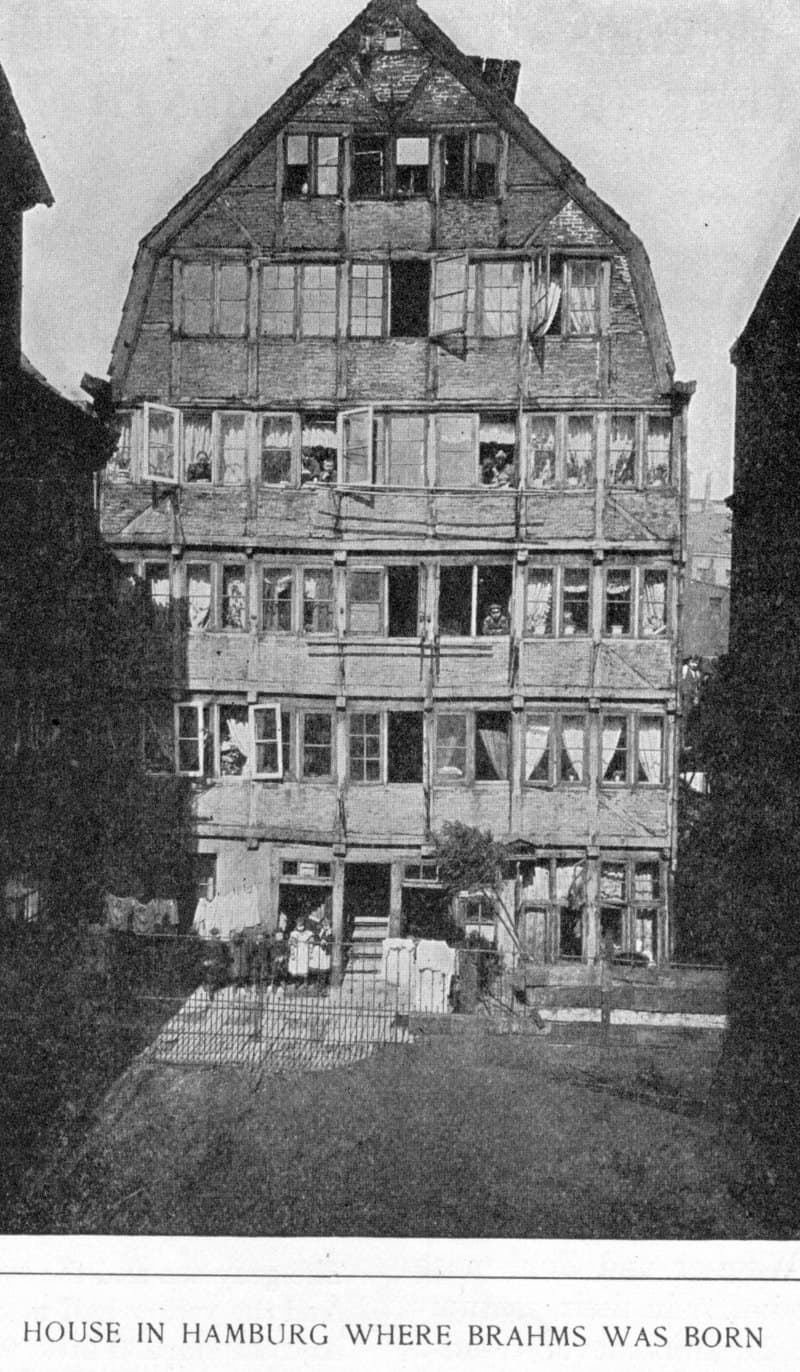

House in Hamburg where Brahms was born

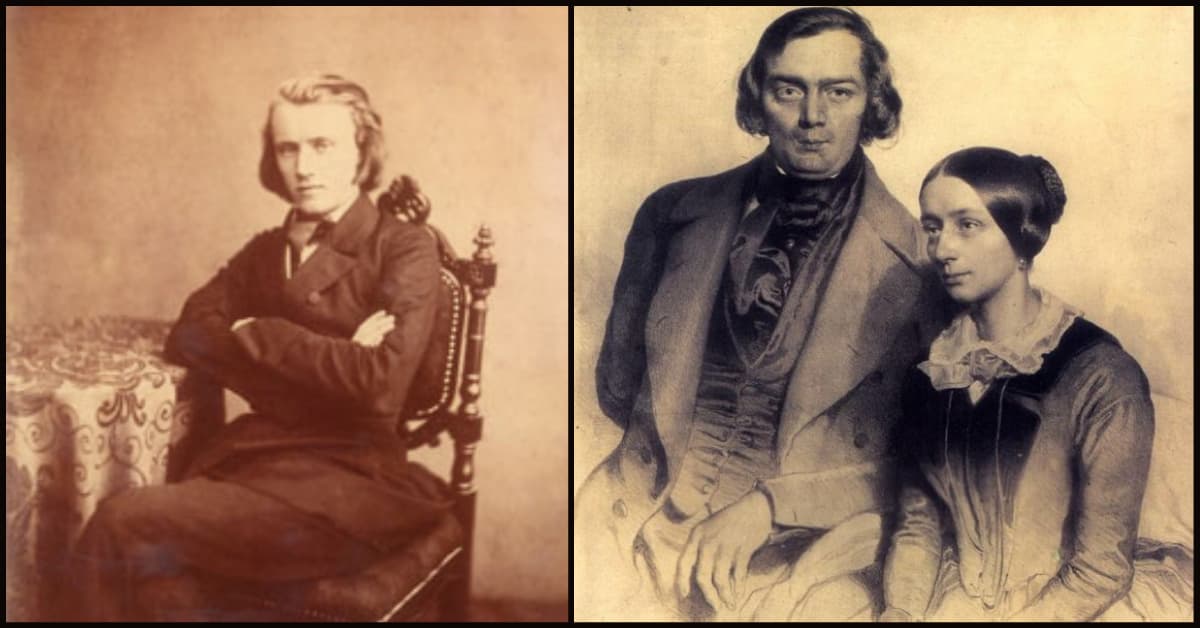

The story goes that Brahms had barely finished the first page when Schumann stopped him and called out for Clara to join them. Both listened intently, and they invited Brahms to come back for lunch the next day. Robert simply wrote in his diary, “Brahms from Hamburg—a genius.” Clara, on the other hand, provided a much more detailed report.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Sonata No. 1 in C Major, Op. 1

She writes, “This month introduced us to a wonderful person. Brahms, a composer from Hamburg, 20 years old. Here again, is one who comes as if sent from God. He played us sonatas, scherzos, etc, of his own, all of them showing exuberant imagination, depth of feeling, and mastery of form. Robert says that there was nothing that he could tell him to take away or add… It is really moving to see him sitting at the piano with his interesting young face which becomes transfigured when he plays, his beautiful hands which overcome the greatest difficulties with ease (his things are very difficult), and in addition to these remarkable compositions. …What he played to us is so masterly that one cannot but think that the good God sent him into the world ready-made. He has a great future before him, for he will first find the true field for his genius when he begins to write for the orchestra. Robert says there is nothing to wish except that heaven may preserve his health.”

The young Johannes Brahms and the Schumanns

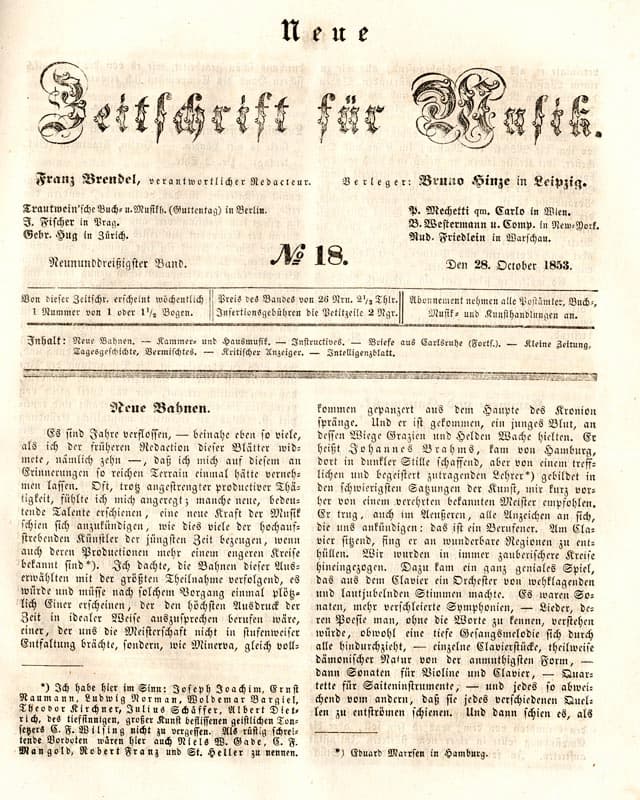

In the event, Brahms stayed with the Schumanns for several weeks and became a close family friend. Clara gave him piano lessons, and she mentioned him daily in her diary. That encounter had far-reaching personal and musical consequences, specifically after Robert went public with a lengthy article in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik on 28 October 1853.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Sonata No. 2 in F-sharp minor, Op. 2

Titled “Neue Bahnen,” (New Paths), Schumann writes. “Many years have passed, almost as many as I had earlier dedicated to the editorship of these pages, and in those years are memories of such rich terrain, which once made itself heard to me… I thought, that it would and that it must be, that someone would suddenly come along whose very calling would be that which needed to be expressed according to the spirit of the times and in the most suitable manner possible, one whose mastery would not gradually unfold but, like Minerva, would spring fully armed from the head of Jupiter. And now he has arrived, a young blood, at whose cradle graces and heroes kept watch. His name is Johannes Brahms, and he hails from Hamburg, where he has worked in quiet seclusion… Sitting at the piano, he began to explore the most wonderful regions. We were drawn into more and more magical circles by his playing. There were sonatas, or rather veiled symphonies; songs whose poetry might be understood without words; piano pieces both of a demoniac nature and of the most graceful form; sonatas for piano and violin; string quartets, each so different from every other that they seemed to flow from many different sources. Whenever he bends his magic wand, there, when the powers of the orchestra and chorus lend him their aid, further glimpses of the magic world will be revealed to us. May the highest genius strengthen him!”

Johannes Brahms: 6 Gesänge, Op. 3 (Jessye Norman, soprano; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Daniel Barenboim, piano)

Schumann’s “Neue Bahnen” (New Paths)

Schumann’s announcement of the “New Messiah” must have justifiably horrified the painfully shy Brahms. He immediately began to censor his intended publications. Only three weeks after Schumann’s article, Brahms writes, “Above all, it obliges me to exercise the greatest care in my choice of works to be published. I am contemplating not to publish any of my trios…” Schumann’s announcement was apparently the start of Brahms’ life-long obsession with destroying manuscripts of compositions, sketches, and drafts that he considered unworthy. Brahms said that prior to publishing his first string quartet, he had already composed 20 string quartets that have now disappeared. And the manuscript of the Sonata for Piano No. 1, published as Opus 1, is titled “Sonata No. 4.” This path of destructive self-censorship continued well into his maturity, and scholars have suggested that only about one-third of Brahms’ compositional output has survived.

So what happened to the trios Brahms mentioned in the letter? We do know that he published his first trio in B Major as his Op. 8 in 1854, and there might well have been a companion piece. Brahms was in the habit of writing works in pairs, and a manuscript in the hand of an unknown copyist was found amongst the papers of Dr. Erich Prieger. Prieger was a renowned music collector in Bonn, and we know that Brahms spent part of the summer of 1853 in that city. A musicologist attributed the work to Brahms, and it was first published as the Piano Trio in A Major in 1938. It certainly is plausible that this is one of the trios Brahms mentioned in his letter.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Trio in A Major (Guarneri Trio Prague)

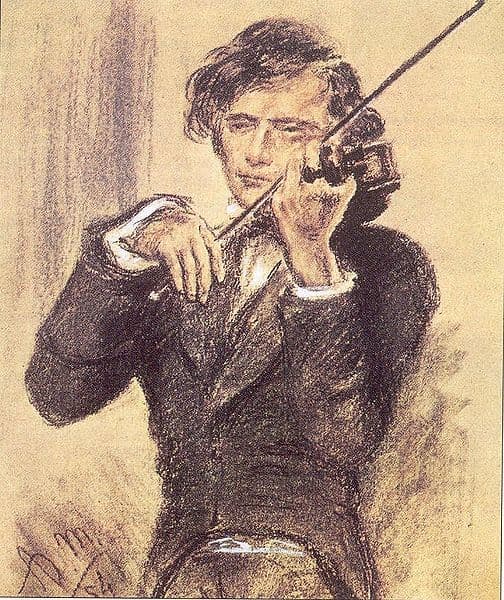

Joseph Joachim, 1853

Actually, Brahms had already published a number of piano arrangements and fantasies in 1849. The Hamburg music publisher August Cranz, father of Brahms’ piano student and friend Alwin Cranz, encouraged the composer “to provide savoury arrangements of favourite operatic melodies for the retail trade.” Brahms went to work and Cranz issued the arrangements undated and without plate numbers, and he did hide the name of the actual author behind the collective nom de plume “G. W. Marks.” The category of pseudonymously published arrangements is still shrouded in obscurity. For one, none of the original manuscripts have survived. It has long been assumed, however, that they originated during a period when Brahms supposedly played the piano in taverns and seedy establishments around the Hamburg docks.

As an early biographer wrote, “Too early he came to know the active, frivolous, purchasable sexuality of the prostitute. He once told of scenes he had witnessed of the sailors who rushed into the inn after a long voyage, greedy for drinks, gambling, and love of women, who, half-naked sang their obscene songs to his accompaniment, then took him on their laps and enjoyed awakening his first sexual feelings.” These stories of Brahms playing in bars and brothels have been persistently passed on, but a majority of modern scholars readily dismiss them. For one, Hamburg legislation at that time strictly forbade music in, or the admittance of minors to, brothels.

Johannes Brahms (G. W. Marks): Souvenir de Russie

Apparently, Brahms fashioned additional arrangements under the name “Karl Würth,” and he certainly contributed to a tribute for the violinist Joseph Joachim. The so-called F-A-E Sonata, a four-movement work for violin and piano, was the brainchild of Robert Schumann. He enlisted his student Albert Dietrich and the young Johannes Brahms in October 1853 to contribute movements based on Joachim’s personal motto “Frei aber einsam” (Free but lonely). Schumann decided that all four movements had to contain the musical notes F-A-E, the motto’s initials, as a musical cipher. Dietrich was tasked with composing the first movements, and Schumann wrote a short “Intermezzo” as the second movement. The “Scherzo” was handed to Brahms, and Schumann provided the “Finale.”

Albert Dietrich

On the autograph score, Schumann penned the following dedication “F.A.E.: In expectation of the arrival of their revered and beloved friend, Joseph Joachim, this sonata was written by R.S., J.B., A.D.” This collaborative effort was presented to Joachim on 28 October 1853 at a soirée in the Schumann household. Joachim performed the work, and when challenged to identify the author’s of individual movement, he did so with ease. The Brahms “Scherzo” was first published in 1906, and the complete sonata in 1935.

Schumann/Brahms/Dietrich: F-A-E Sonata

Once Brahms had actually decided on publishing works under his own name, he sent the Piano Sonatas No. 1 and 2, the Six Songs Op. 3, and the Scherzo Op. 4 to the Leipzig publisher Breitkopf & Härtel. In his letter of recommendation, Schumann once again heaped high praise on Brahms, and Brahms subsequently writes to Schumann. “I delayed writing to you until I had sent the four works above mentioned to Breitkopf and received their answer so that I might tell you at once what the result of your recommendation was. But this we have already found out from your last letter to Joachim. So all I have to say for the present is that, in accordance with your advice, I shall go to Leipzig within the next few days, probably tomorrow. Furthermore, I should like to tell you that I have copied my Sonata in F minor and have considerably altered the finale. I have also improved the violin sonata.”

Here, Brahms might simply have referred to his “Scherzo” from the F-A-E instead of referencing an independent work. With the first four opus numbers accepted, Brahms offered his Third Piano Sonata Op. 5 and the Six Songs Op. 6 to the publisher Bartholf Senff. The combination of poetry and music held special meaning for Brahms, and in all, he published 33 collections of Lieder based on texts by predominantly minor poets. His choice of texts is frequently criticized, but he believed that the great poems by Goethe, Heine, and Rückert were of such perfection that music could add very little. In the poetry he did set, Brahms found themes that echoed his own feelings, evoking deep inner sentiments of unattainable love, the loneliness of the human condition, and the redemptive power and comfort of nature.

Johannes Brahms: 6 Gesänge, Op. 6 (Jessye Norman, soprano; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Daniel Barenboim, piano)

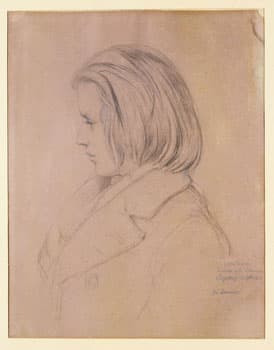

Johannes Brahms at 20 years old

Combining the experiences gained from composing his previous two piano sonatas, the F-minor Piano Sonata Op. 5 is considered the fullest expression of Brahms’ early genius. In fact, it has been called “one of the three greatest piano sonatas of the mid-nineteenth century.” In his Op. 1, Brahms provided a stern testament to the Classical form, while Op. 2 was endowed with Romantic passion. For scholars, Op. 5 is the synthesis of the two. Scored in five movements, the music critic Eduard Hanslick writes, “The whole of Brahms is here, though still under the spell of Schumann.” The opening movement is heroic and assertive, and the slow movement is headed by a Sternau poem, “The twilight falls, the moonlight gleams, two hearts in love unite, embraced in rapture.” Pianist Claudio Arrau considers this second movement “the most beautiful love music after Tristan.” The entire movement is written in tender simplicity, “as if the music floats and doesn’t touch the earth.” After a fiery scherzo, Brahms inserts a short movement entitled “Rückblick” (a backward glance). Brahms is longingly looking back to the slow movement, which by now has undergone a remarkable transformation. The work concludes with a restless Rondo. Op. 5 was to be Brahms’ final piano sonata, as he never again returned to that particular genre.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Johannes Brahms: Piano Sonata No. 3 in F minor, Op. 5