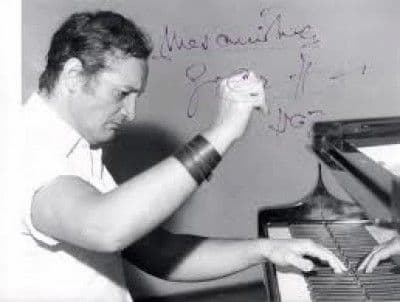

György Cziffra, born in Budapest on 5 November 1921, must be counted among the greatest pianists of the twentieth century. “Born with outstanding talent in circumstances of dire poverty, he survived war, imprisonment and hard labor as a political prisoners, which left his hands and wrists seemingly permanently damaged.” Yet, he persevered and rebuilt his career until he was able to escape with his family to the West in 1956. His debut recital in Vienna caused a sensation, and additional concerts in Paris and London confirmed his extraordinary virtuoso status. While he was greatly admired by such colleagues as Alfred Cortot and Martha Argerich, his recitals featuring his own brilliant paraphrases were considered “brilliantly vulgar confections.”

György Cziffra

Cziffra himself said about his playing, “I became the profession’s Antichrist due to my improvisations, which multiplied the difficulties ten times over.” His play was always characterized by an unconditional spontaneity and the impulsiveness of the moment, and many critics denied him the ability “to interpret works that are less virtuosic in a coherent and true-to-the text manner.” Mind you, it was Vladimir Horowitz who famously said, “I want to be Cziffra.”

György Cziffra Plays Ravel, Chopin, and Liszt

Cziffra was born in almost indescribable poverty. As he writes in his memoirs Cannons & Flowers, “inexorable poverty enshrouded my mother, sisters and me in the single tiny room where we lived. It beat incessantly against the walls and against the bathtub into which I fell when I was born. With it came destitution and, worst of all, starvation. It assailed us until I was eight, passing over me without crushing the little child that I was or ruining my health, despite the paralyzing effect it had on us.”

His parents had actually lived in Paris, but after the declaration of war in 1914, the French government issued a decree expelling all foreign residents whose countries of origin were fighting against France. His father, a Hungarian who had made his living as a cabaret musician, was immediately arrested, and his mother given notice to leave the French territory without delay. Once the family reunited in Budapest, his parents were forced to let their youngest child be adopted by a Dutch family so they had one less mouth to feed. His older sister finally found a job doing the washing-up in a canteen, and one day, she brought home a piano.

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: Tale of Tsar Saltan, Op. 57 – Le vol du bourdon (Flight of the Bumblebee) (arr. G. Cziffra for piano) (György Cziffra, piano)

Yolande Cziffra taught herself how to play the piano, and György, just having turned three years of age, learned by mimicking her. He writes, “at the time we did not have any sheet music, which did not bother me since I was unable to read the notes in any case. I pestered my mother to sing me tunes, and I usually retained them after a single hearing and let my fingers run over the keys. It was child’s play to me. I grew more ambitious, inventing introductions for the little tunes and embellished them more and more, and when my left hand could react as quickly as my right, I started on variations.” Cziffra became a member of a traveling circus at the age of 5, improvising on popular motifs that were called out to him by the audience. “My fingers flew from “Carmen” to “La Vie Parisienne” without pause, he writes, “with a few Viennese waltzes in passing.” The prodigy child was gaining a reputation around town, and by sheer coincidence he was accepted, at the age of nine, as the youngest student ever to study at the Franz Liszt Academy under the tuition of Ernő Dohnányi.

György Cziffra Plays Schumann’s Faschingsschwank aus Wien, Op. 26

Cziffra’s incredible talent initially puzzled his first teachers at the Academy. As he wrote, “my talent was a form of bond with my instrument that permitted my manual skills to make sense of and straightway put into practice all I learnt from the sort of methodical teaching which seems an avalanche of odds and ends to most children. Things incomprehensible to me at ten became conditioned reflexes activating my hands before my brain could provide a rational explanation.” The solution was to have him attend piano master classes with Istvan Thomán, who was a favorite student of Franz Liszt, and later taught Bartók and Dohnányi.

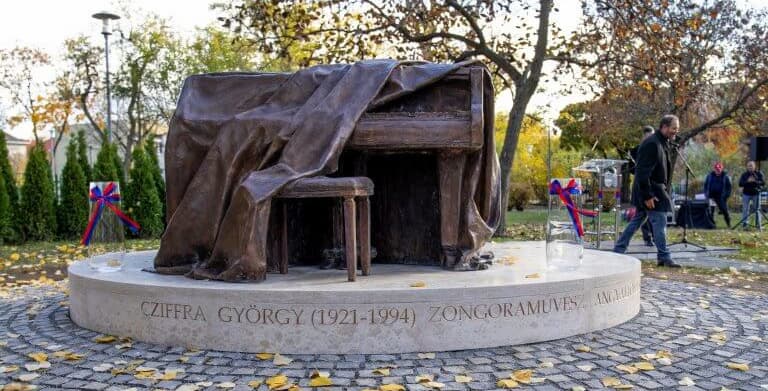

The Cziffra statue in Budapest

Cziffra’s education was cruelly interrupted when he was drafted in the Hungarian Army and deployed to the Eastern Front in Ukraine. He was captured by Russian partisans and held as a prisoner of war. After attempting to escape on a number of occasions, he was deported to a gulag. After the war, he earned a living playing in Budapest bars and clubs, and after a failed attempt to escape from Stalinist Hungary, Cziffra was punished with forced labor in Sopronkőhida prison from 1950 to 1953. “While in prison,” he writes, “I had been accorded the privilege of transporting blocks of stone.” He needed four months of physiotherapy after leaving prison “in order that my fingers, swollen by work of a very different nature, could gradually grow used to the piano again. I was obliged to continue wearing wristbands to hold my joints in place and lessen the pain. I was to wear these accessories for the rest of my life.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

György Cziffra’s BBC broadcasts

I have never heard that Horowitz said he wanted to be Cziffra. Do we have a source?

Quote taken from:

https://medium.com/@stn1978/györgy-cziffra-caa00a0a725e

Original source unknown

Cziffra was a genius! Far from the regular pianism we hear these days.