Giuseppe Verdi, 1870

After the enormous success of Aida in 1871, Giuseppe Verdi decided on an early retirement. He still had things to say, but as a composer who had been at the forefront of Italian musical taste for two decades, he now found himself accused of being old-fashioned. A scholar writes, “Verdi seemed increasingly isolated from current trends in Italian music, in particular by the tendency of both public and composers to look outside Italy (to France and, later, even more to Germany) for new ideas and aesthetic attitudes.”

Alexandre-Marie Colin: Otello and Desdemona

In fact, Verdi entered a period of gloom and depression, and “his letters at the time are full of complaints about the Italian theatre, Italian politics, and Italian music in general.” The young and ambitious director of the Ricordi publishing house, Giulio Ricordi, made it his mission to coax Verdi out of retirement. Ricordi immediately knew that it wasn’t going to be an easy task, so he tried his luck with a partly finished libretto to the opera Nerone by Arrigo Boito. Ricordi suggested to Verdi that he might set it to music, but the composer simply ignored his letter.

Giuseppe Verdi: Otello, Act 1 “Finale”

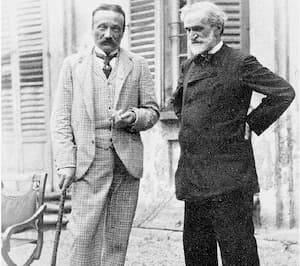

Arrigo Boito and Verdi

Ricordi also understood that Verdi was highly selective when it came to his choice of subjects. He tried again to arouse the composer’s interest in January 1871. This time he sent him the Boito libretto to Amleto, which had already been set by Franco Faccio in 1865. Based on Shakespeare’s play Hamlet the opera was a success, and “aroused unusual and profound emotions in the Genovese public…The curtain-calls for unanimous, insistent, continuous, and even warmer as the imaginative work unfolded before the eyes of the listeners who were highly surprised with the truth of its conception, the newness of form, the passion of the melodies, the ensemble harmony, and of the robust skill that dominates the whole score.”

Otello Act 3, 1887

Verdi had been aware of the success of the opera, and he wrote to his librettist Francesco Maria Piave, “If Faccio succeeds, I am sincerely happy; others will perhaps not believe this; but only others; you know me and you know that I either keep quiet or say what I feel.” In 1871, Amleto was in the process of being revised for a La Scala production, and Ricordi tried to enlist Verdi’s help. He even wrote, “The whole salvation of the theatre and the arts is in your hand,” to which Verdi replied, “I cannot take it as but a joke. Oh no, never fear, composers for the theatre will never by lacking.”

Giuseppe Verdi: Otello, Act 2 “Finale”

Alfredo Edel Colorno: Desdemona (soprano),

costume design for Otello act 4 (1887)

As Verdi’s refusals continued, Ricordi tried a different approach. He was well aware that Verdi had shown keen interest in the soprano Adelina Patti. In fact, Verdi had described her as “perhaps the finest singer who had ever lived, and a stupendous artist.”

Romilda Pantaleoni as the first Desdemona

Ricordi’s plan was to entice Verdi into writing a tailor-made opera for her, but Verdi refused. Ricordi even tried to enlist the composer’s wife Giuseppina, but the composer would not relent. Even the countess Clara Maffei, who was well known for the salon she hosted in via dei Tre Monasteri in Milan, tried to interest Verdi, but he curtly replied “For what reason should I write? What would I succeed in doing?” In May 1879, Ricordi tried to engage Verdi for a revision of Simon Boccanegra. Initially, Verdi declined and wrote “it will remain untouched just as you sent it to me.” In the end, however, Verdi relented, and collaborating on the revision of Simon Boccanegra with Boito convincing the composer of the librettist’s abilities. Ricordi reports, “The idea of a new opera arose during a dinner among friends, when I turned the conversation, by chance, on Shakespeare and on Boito. At the mention of Othello I saw Verdi fix his eyes on me, with suspicion, but with interest. He had certainly understood; he had certainly reacted. I believed the time was ripe.”

Giuseppe Verdi: Otello Act III Finale

Francesco Tamagno in the title role of Verdi’s opera Otello in the

original 1887 production

Verdi held a lifelong veneration for Shakespeare, and he understood that Boito, “a highly cultured poet and musician was as serious about getting to the true meaning of Shakespeare as was Verdi himself.” Verdi showed cautious enthusiasm for the new project, and by the end of the year Boito had produced a draft libretto, “one full of ingenious new rhythmic devices but with an extremely firm dramatic thread.” However, the process of composition was anything but smooth.

Verdi “completed the work in three comparatively short bouts of composition. The first, very brief, was at Genoa in March 1884, five years after the first drafts of the libretto began. The second, the principal one, at Genoa from December 1884 to April 1885, and the third at Sant’ Agata from the middle of September to early October 1885.”

Press illustration of the 12 October 1894 Parisian premiere of the opera Otello,

performed by the Paris Opera at the Palais Garnier

in a French translation by Arrigo Boito and Camille du Locle

Throughout the process, Verdi demanded frequent alterations to the libretto, particularly to the Act 3 finale. Finally, on 1 November 1886 Verdi proclaimed, “Dear Boito, it is finished! All honour to us! (and to Him!) Otello premiered to resounding success at the Teatro alla Scala, Milan, on 5 February 1887. Verdi took 20 curtain calls at the end of the opera, and the work soon appeared on all major European stages. To this day, “Otello remains one of the most universally respected of Verdi’s operas, often admired even by those who find almost all his earlier works unappealing.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Giuseppe Verdi: Otello, Act 4