Charles-Valentin Alkan (1819-1888) was one of the most celebrated pianists of the nineteenth century, mentioned in the same breath as Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt. He was also a most unusual composer, “remarkable in both technique and imagination,” and compared with Hector Berlioz. Painfully shy and reclusive, Alkan was prone to extensive bouts of depression, and he withdrew into virtual seclusion for decades on end. Almost predictably, he was completely ignored by subsequent generations.

Charles-Valentin Alkan: Concerto for Solo Piano, “Allegretto all barbaresca”

Heritage

Charles-Valentin Morhange (Alkan)

Born Charles-Valentin Morhange on 30 November 1813 at 1 Rue de Braque in Paris to Alkan Morhange (1780–1855) and Julie Morhange, née Abraham, the family name comes from a long-established Jewish Ashkenazi lineage. Their ancestors had migrated from Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages to form a self-governing community in a little Alsatian town of the same name, located roughly 30 miles from the city of Metz. The more enterprising members of the family moved to Paris and settled in the ancient area of Marais, and Marix Morhange, the composer’s grandfather, was well-established by 1780.

Alkan Morhange operated a little boarding school in the Rue des Blancs-Manteaux, where young Jewish children received elementary education in music and French grammar. He was described as hardworking and intelligent, and he married Julie Abraham on 12 April 1810. Charles-Valentin was the second of six children, and his birth certificate indicates “that he was named after a neighbour who witnessed the birth.”

Charles-Valentin Alkan: Concerto da camera No. 3 in C-sharp minor (Dmitry Feofanov, piano; Razumovsky Symphony Orchestra; Robert Stankovsky, cond.)

At the Conservatoire de Paris

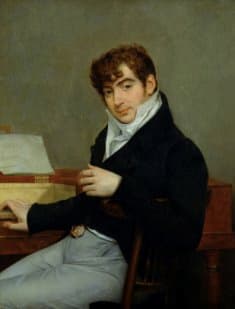

Pierre-Joseph-Guillaume Zimmerman

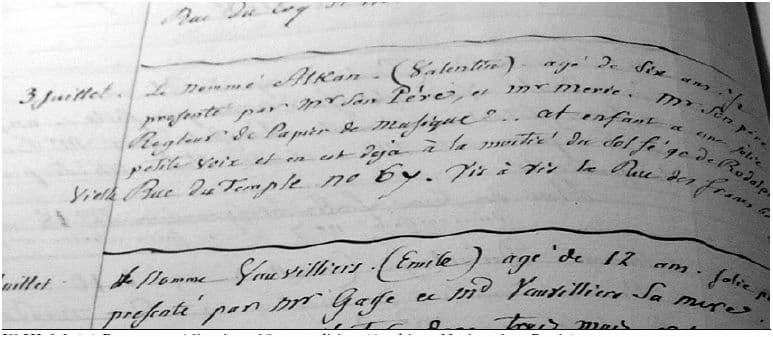

The Morhange children adopted their father’s first name as their last at an early age, and Charles-Valentin was an incredible child prodigy. He could sing elaborate melodies before he could walk or talk and probably learned all kinds of musical matters from his big sister Céleste, who was training to be a singer. He applied to enter the Conservatoire de Paris on 3 July 1819, being a mere 5 years and 7 months old. At his solfège audition, the examiners noted Alkan “having a pretty little voice.” And at his piano audition in 1820, the examiner commented, “This child has amazing abilities.”

In 1821, young Valentin made his first public appearance as a violinist, but it was his piano skills that attracted attention. He was accepted as a member of the class of Joseph Zimmermann, the most celebrated piano teacher at the Conservatoire and a former student of Cherubini. Zimmermann would subsequently teach Georges Bizet, César Franck, Charles Gounod, and Ambroise Thomas, but he publicly declared late in life that Alkan was his favourite student.

Charles-Valentin Alkan: 3 Etudes de bravoure, Op. 12 (Laurent Martin, piano)

The Salon Circuit

Alkan’s conservatoire report in 1819

Apparently, Alkan was a sickly child, frequently absent from instruction at the Conservatoire. However, nothing stood in his way of rapid development, and he won first prizes in solfège at the age of seven and prizes in piano (1824), harmony (1827), and organ (1834). Zimmermann was eager to introduce his charge to the leading musicians in Paris, and Rossini described him as “that wonderful child.” Alkan’s first opus, a set of variations on a theme by Daniel Steibelt, dates from 1828.

Alkan enjoyed great success as a child prodigy in the salon of the Princesse de la Moskova, and his first public recital was announced as follows, “The young Alkan, whose precocious talent is the subject of admiration for lovers of firm and brilliant technique on the piano, proposes to give a concert on April 2nd and is desirous of obtaining for his musical gathering a subscription from the Department of Fine Arts. This artist, aged only 11 years, is granted the encouragement he requests.”

Charles-Valentin Alkan: 3 Morceaux dans le genre pathétique, Op. 15 (Vincenzo Maltempo, piano)

Success and Rejection

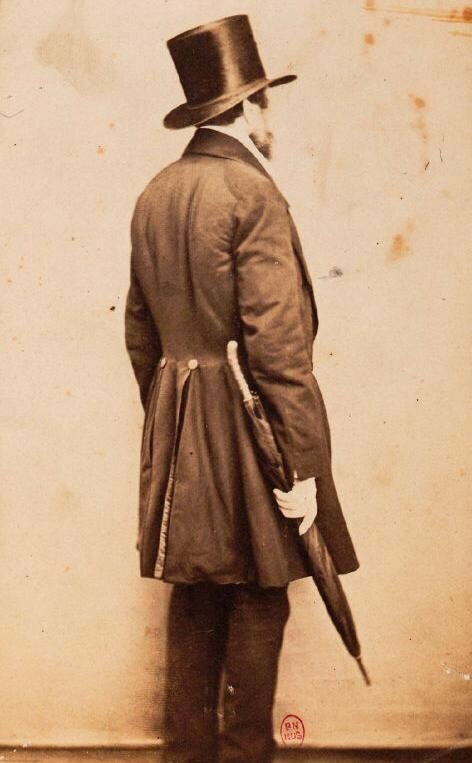

One of two known photographs of the reclusive Alkan, date unknown

Alkan continued to appear in concerts with the leading musicians of the day, including sopranos Giuditta Pasta and Henriette Sontag, the cellist Auguste Franchomme and the violinist Lambert Massart. His career as a virtuoso was well on its way, and Alkan set out for London in 1833 to establish contact with some publishing houses. There seems to be no record of Alkan having actually performed, but we know that he visited the celebrated pianist Henry Field, who subsequently gave the first performance of Alkan’s second “Concerto da Camera.”

In addition, his musical and intellectual faculties, according to a critic, “have shown a remarkable development,” and one of his compositions was called “remarkable for its form and style, which are new.” He made friends with Franz Liszt, Eugène Delacroix, George Sand, and Frédéric Chopin and continued to publish piano music. Not everybody was impressed, however, as Robert Schumann wrote, “One is startled by such false, such unnatural art…the last piece titled ‘Morte’ is a crabbed waste, overgrown with brush and weeds…nothing is to be found but black on black.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter