J.S. Bach, 1748

At the age of 57, Johann Sebastian Bach started to experience a number of health problems. Most serious was an affliction to his eyes, a condition that seemingly had plagued him from a young age. “His eyes had naturally bad vision, and that was further weakened by a lot of studying, sometimes even all night long, especially during his youth.” Present-day ophthalmologists, having studied a number of paintings, suggest that Bach “was probably mildly myopic.” Bach’s only known period of sickness occurred between 1730 and 1740, when he had to cancel a trip to Halle to meet George Frideric Handel. However, nothing is known about the nature and duration of this particular illness. We do know, however, that his eyesight got progressively worse over the years, probably caused by prolonged diabetes. Recently, it has been suggested that “neuropathy and degenerative brain disease, as evidenced in a dramatic change in his handwriting,” might also have been a factor. In the event, cataracts eventually severely restricted Bach’s ability to work.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Goldberg Variations, BWV 988

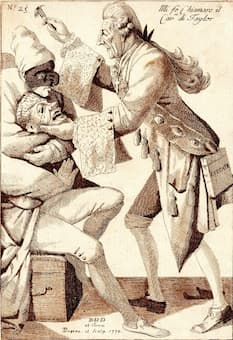

Cacicature of John Taylor, 1770

A number of close friends persuaded Johann Sebastian Bach to have his eyes operated on. As such, he underwent an eye operation performed by the traveling specialist “Chevalier” John Taylor, who would later perform a similar operation on Handel. Taylor had received his surgical training in England, and he attended lectures in the Netherlands and France. Taylor set up a practice in Switzerland, where “he blinded hundreds of patients,” as he once proudly confessed. “During his working life, he spent most of his time traveling around a coach painted all over with eyes and the words “qui dat videre dat vivere (giving sight is giving life.)” Taylor counted kings and emperors among his patients, and he did write scientific articles in several languages. In the words of a medical expert, “Taylor was a rare combination of a man of serious science and a charlatan in daily practice.” In accordance with the convention of his time, Bach was presumably operated on both eyes while seated upright in a chair and held tightly by a helper, “who made sure the patient did not move at crucial moments in this era without anesthetics being in common use.” I spare you the grisly details, but besides being incredibly painful, the operation was only partly successful.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Art of the Fugue, BWV 1080

Grave of Bach at St. Thomas Church, Leipzig

The first operation on Bach took place between 28 and 31 March 1750, and it had to be repeated one week later. “What exactly took place during the operations will never be known, but Taylor’s general approach included bloodletting, laxatives, and eye drops of blood from slaughtered pigeons, pulverized sugar, or baked salt. He sometimes made periocular incisions, which then got covered with bandages that incorporated baked apples or a coin. In cases of serious inflammation, Taylor prescribed large doses of mercury.” Biographies indicate that Bach was completely blind after the second operation, and that “he felt ill and experienced painful eyes.” Bach never recovered after the operations. Supposedly, his vision returned a few days before his death; however, this was likely caused by “Charles Bonnet syndrome, in which patients experience complex visual hallucinations.” Bach subsequently suffered a stroke and “burning fever,” in other words a severe infection, causing fatal sepsis. Bach died at 6:15 pm on 28 July 1750, and he was buried anonymously three days after his death, “in a grave without any obvious stone or mark, near the St Johannes Church in Leipzig.”

Johann Sebastian Bach: “Before thy throne I now appear,” BWV 668

Bach’s statue at St Thomas Square, Leipzig

Johann Sebastian Bach left a modest estate that was divided between the widow and the nine surviving children of both marriages. He also gave clear instructions for the disposition of this musical estate, but according to the Bach biographer Forkel, Wilhelm Friedemann got most of it. Anna Magdalena survived her husband by ten years, and she died in abject poverty in 1760. Bach’s oldest daughter, Regina Susanna Bach remained in Leipzig until her death in 1809. She appeared to have struggled with poverty throughout. In fact, Friedrich Rochlitz, the founder and editor of the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, had to print a public plea for funds to assist her in May 1800. When the St Johannes Church in Leipzig was rebuilt in 1894, the oak coffin containing Bach’s remains was exhumed. A detailed anatomical investigation by Professor Wilhelm confirmed Bach’s identity. Bach’s remains were subsequently reburied in the church itself. When that church was practically destroyed during World War II, his remains were moved to the St Thomas Church across town, where they remain to this day. The old St Thomas School, which included Bach’s last residence, was demolished in 1902. In its place, a Bach monument was created by Carl Seffner and placed in the Center of St Thomas Square in 1908.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Johann Sebastian Bach: Mass in B minor, BWV 232