Born on 25 January 1886 in Berlin, Wilhelm Furtwängler still inspires acrimonious debates surrounding his “role as de facto chief conductor of the Nazi regime,” his passive political resistance, and his outspoken opinions on the relationship between art and politics. While these issues will be debated for decades to come, it is clear that Furtwängler was consumed by his belief in the power of music, and the supremacy of German art.

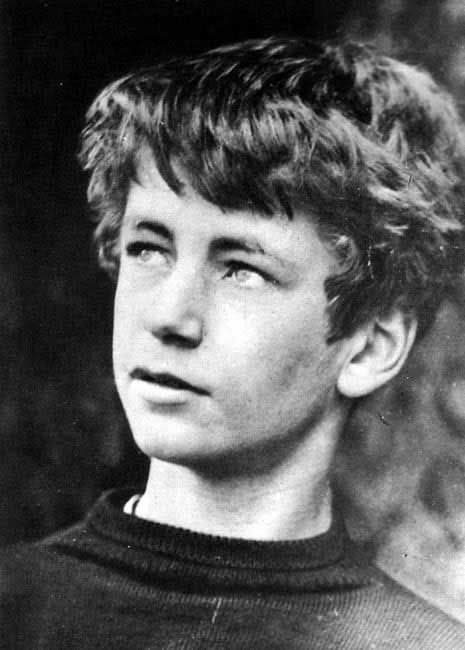

Wilhelm Furtwängler as a boy

As a critic wrote, “Furtwängler conducted Beethoven and Brahms, Bruckner and Wagner, with proprietary authority, as if he alone could reveal their deepest psychological, even spiritual, secrets. With his expressive, flexible approach to tempo and dynamics, Furtwängler breathed the structure of a whole piece into each of its measures, while making each measure sound as if improvised.” With its deliberate imprecisions and its privileging of the perceived spirit behind the music over its textual details, Furtwängler’s style stood in diametric opposition with the textual literalism of his rival Arturo Toscanini. Furtwängler was, unapologetically conservative and nationalist in his worldviews, and above all, he hated modernism and the “biological insufficiency of atonality.”

Furtwängler Conducts Wagner’s Die Meistersinger “Overture” (1942)

Furtwängler Family Background

Furtwängler at age 18

Furtwängler saw the future of music with tonality rather than with the eclectic individualism he found unsatisfactory. “Universal things,” he wrote in 1940, “can only be said in a universal language.” He was born into a prominent family in the Schöneberg district of Berlin. He was the eldest child of the classical archaeologist Adolf Furwängler and the painter Adelheid, née Wendt. Growing up in the cultivated and liberal atmosphere of Germany humanism, Furtwängler spent most of his childhood in Munich, as his father was appointed professor at the Ludwig Maximilian University. The boy showed early signs of exceptional talents, and his mother reported, “that as a three-year-old, he already sung songs in tune, almost without a mistake, and that he started to invent his own melodies.” His parents decided to have him home-schooled, and among his tutors were the archaeologist Ludwig Curtius, the sculptor Adolf Hildebrand and the art historian and musicologist Walter Riezler. He spent some time at Hildebrand’s house outside Florence, and he also accompanied his father on an excavation of the Island of Aegina in Greece.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Leonore Overture No. 3, Op. 72b (Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra; Wilhelm Furtwängler, cond.)

Early Musical Training

His parents also encouraged his musical training, and the boy took piano and violin lessons. He started lessons in music theory in 1897 at the age of eleven with the Munich composer and composition teacher Anton Beer-Walbrunn, continuing later with the composer Joseph von Rheinberger and Max von Schillings. Furtwängler wrote his first composition, the song “A little piece about animals” in 1893, and he proudly inscribed it as his “Opus 1.” By the age of twelve he had completed a choral setting of “Die erste Walpurgisnacht” from Goethe’s Faust, in addition to a substantial number of other compositions. A scholar writes, “Despite the breadth of his artistic sympathies, it was music that absorbed him most.” For Furtwängler, “music began where the other arts left off.” By the age of 17, Furtwängler had written several substantial works, including a string sextet, several quartets, trios and sonatas and a Symphony in D. The work was performed in Breslau during the 1903/4 Season, and it was a decided failure.

Wilhelm Furtwängler: Symphony in D Major “Allegro” (Slovak State Philharmonic Orchestra, Košice; Alfred Walter, cond.)

A Career as a Conductor

Furtwängler had long nurtured the ambition to be a composer, but he decided to take up conducting instead. A musicologist writes, “he came to conducting through a combination of three separate factors: the wish to be able to conduct his own music; the passionate interest he had begun to take in the art of interpretation, an interest arising in the first place from his fascination with the music and mind of Beethoven; and the practical necessity of earning a living so as to be able to support himself and his mother after the death of his father in 1907.” Furtwängler was appointed principal conductor of the Mannheim Opera and Music Academy in 1915, and he remained until 1920. He had known the city since childhood, as it was the hometown of his grandmother. As a boy, he made friends with the Geissmars, a Jewish family who were leading lawyers and amateur musicians in the town. Berta Geissmar reported, “Furtwängler became so good at skiing as to attain almost professional skill… Almost every sport appealed to him: he loved tennis, sailing and swimming… He was a good horseman, and a strong mountain climber and hiker.” By 1920, he was appointed conductor of the Berlin Staatskapelle succeeding Richard Strauss, and two years later to over the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra in the succession of Arthur Nikisch.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Furtwängler Conducts Richard Strauss’ Till Eulenspiegel

Deze buitengewoon begaafde en hyperromantische ziel, die dirigeert “Nach der Natur” zoals geen ander, die met zijn toverstokje een wereld schept, zo onuitsprekelijk mooi, die ver boven de partituur zweeft met zijn gehele orkest, die is onsterfelijk. Hij, Furtwängler, is voor mij de allergrootste !!!