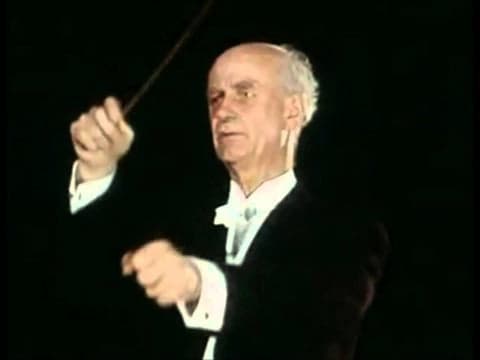

Wilhelm Furtwängler (1886-1954) is known as one of the greatest conductors of the 20th century, but he saw himself primarily as a composer for whom conducting was “the roof under which I have taken refuge in life because I was on the point of going under as a composer.”

Wilhelm Furtwängler

Only 10 weeks before his death, he wrote to the conductor Rolf Agop, “You have to bear in mind that for me the episode of ‘my compositions and the public’ is like a gaping wound. I am convinced, without wanting to overestimate myself that in the whole history of music,/// there was not one real composer (and I have to count myself as one) who had such a wrong and unsatisfactory status with the public from the start as I do, as my compositions are not only demanding and in opposition to the fashion of the day, but also because I stand under the prejudice of the conductor, my age, etc.”

Furtwängler’s Earliest Compositions

Wilhelm Furtwängler at the piano

His earliest compositions were written for piano, or for voice and piano. He had an affinity for the poetry of Goethe, and his songs show great sensibility towards the verse, “conveyed through a natural declamation of the text and vocal melody.”

Wilhelm Furtwängler: “Erinnerung” (Guido Pikal, tenor; Alfred Walter, piano)

His Large-Scale Orchestral Compositions

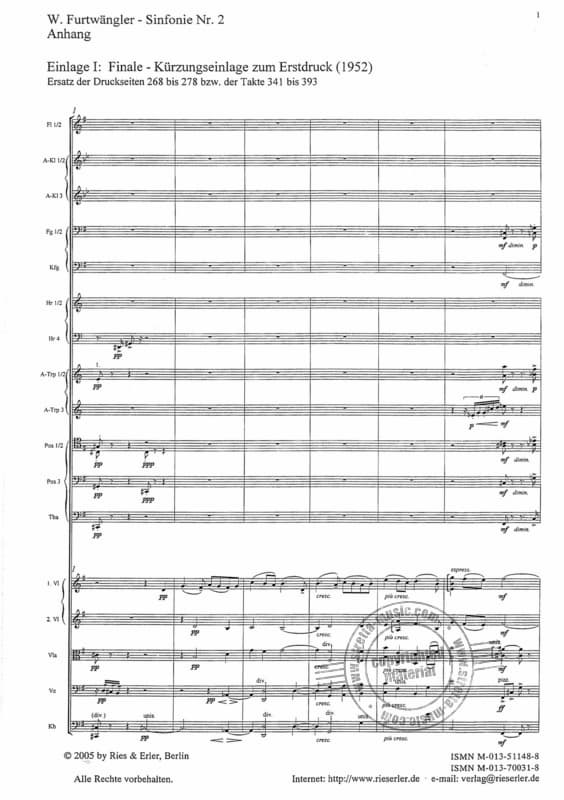

Wilhelm Furtwängler: Symphony No. 2

Already as a boy, Furtwängler tried his hands at large musical forms. As a scholar writes, “His far-reaching intellectual interest, his broad humanistic formation in the 19th century sense, and the wish, already at that time obviously characteristic of Furtwängler, to comprehend and present the world and life in major connections, never allowed him to accept other than large solutions in music.” At the beginning of 1903, Furtwängler was looking to compose “a large orchestral work with chorus and tenor solo” on the text from the conclusion of the second part of Faust. However, his most extensive vocal composition, the Te Deum was first performed in November 1910. He began the work in Florence in 1902, supposedly “under the powerful influence of the Michelangelo figures in the Medici Chapel.” The composition is marked by an abundance of melodic invention, and a forceful and strong motif carries through to the end of the composition. It is contrasted by new motifs, generally appearing in pairs and in expressive melodic lines.

Wilhelm Furtwängler: Te Deum (Frankfurt Singakademie, Oder; Frankfurt Philharmonic Orchestra, Oder; Alfred Walter, cond.)

His Chamber Music

Wilhelm Furtwängler with Igor Stravinsky

Furtwängler considered his two 1930s violin sonatas as cryptic symphonies. While his second sonata was written on the brink of World War II, the first violin sonata had appeared three years earlier. Scored in four movements, the opening movement alone lasts the better part of 20 minutes. A critic characterizes it, as “of Brucknerian length and scale, but it does not have Bruckner’s transcendent mood.” The work is clearly symphonic in its scope, with a mighty climax in the middle of the first movement that serves as an impetus for the rest of the work and is matched by passages of almost total inertia. The splendidly emotional and storm-tossed first movement is followed by a misty and mysterious Adagio and an assertively Brahmsian Moderato. The stressful and overwhelming Finale is only momentarily relieved by passages of hopeful and confidently passionate music. But these moments, according to a critic, “are glorious; like the full glare of sunlight after incarceration.”

Wilhelm Furtwängler: Violin Sonata No. 1 in D minor (Mathias Wollong, violin; Birgitta Wollenweber, piano)

The Symphonic Concerto in B minor

As with a number of other works, the Symphonic Concerto in B minor for piano and orchestra occupied Furtwängler for a number of years. We do know that it was completed in 1936, in Egypt, and was first performed on 26 October 1937 by the pianist Edwin Fischer with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of the composer. Furtwängler kept revising the composition, and the work was finally published in 1954. Fundamentally, it exemplifies Furtwängler’s compositional design, which is based on an intellectual as well as the musical foundation. “Fundamental,” as a scholar writes,” is the conjoining of the organic, the duality, and the tragic. This symbiosis has for corollary three ideas, which the creator invests with a symbolic dimension: form, tonality, and symphonic function. These are the three keystones of Furtwängler’s aesthetic.” In a way, the orchestra and the piano become two separate symphonic entities, struggling against one another, “uniting, loving, and hating.” Drawing on the piano concertos of Brahms, Reger, and Pfitzner, the work is of massive architectural proportions and “the symphonic character of the piano part demands a very physical involvement from the soloist.”

Drawing on his perfect mastery of orchestral technique, Furtwängler succeeds in creating a singular fusion of sound and harmonic language, in that no element is without its purpose.

Wilhelm Furtwängler: Symphonic Concerto in B minor (David Lively, piano; Slovak State Philharmonic Orchestra, Košice; Alfred Walter, cond.)

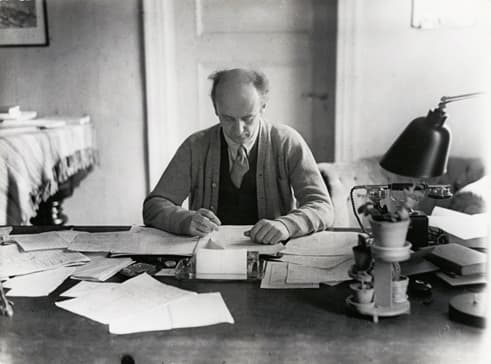

Works that Furtwängler Withheld from the Public

Wilhelm Furtwängler in Potsdam, 1932

Among the works that Furtwängler withheld from the public, we find his first symphony and the Piano Quintet in C Major. We know that Furtwängelr was working on the piece before 1912, but it apparently took another twenty years before the work was completed. As he writes to his teacher and friend Ludwig Curtius, “I myself have the feeling of having done a lot of work this summer, as much as was at all possible. And every day, it seems to me, I grow in clarity, insight, and also in wealth; what I undertake is hard, so hard that no one else dares to try it; but it seems to me unavoidable and the only possibility, at least for me. Of course, I see once again that anything that is to grow needs time, much time, and if I stop this year it is only in the hope that next year it must finally be different. In recent weeks it was sometimes really like a battle of life and death going on for days, and if I did not always emerge the winner, then at least wiser.”

Furtwängler continues, “I hope that next year, when I have five months of time, likewise one of the many things will be properly completed. Surely this is like my conducting over the course of the years: the nervous tension disappears more and more, and the aim, the calm and natural element, appears clearer and easier; it is what anyone really undertaking to speak with the voice of our times considers virtually impossible.”

The musicologist Walter Riezler encountered fragments of the quintet in 1932 and called it “a personal statement of the greatest power which overwhelms the listener, and a force of form, which succeeds in condensing the over-dimensional movements into a closed form. The tonal language is of the greatest nobility, very self-sufficient, and unique. But all is somewhat exaggerated, not only in its dimensions but also in its expression…It seemed not at all like chamber music but thoroughly orchestral and symphonic.”

Wilhelm Furtwängler: Piano Quintet in C Major (François Kerdoncuff, piano; Nomine Sine)

Furtwängler’s Last Symphonic Work

Furtwängler’s tomb in Heidelberg

Furtwängler began work on a Third Symphony in July 1946, and described it to a friend as “a smaller and lighter symphony.” The irony of this statement is immediately audible, as the work is “stamped with the tragedy of its time of origin, of a crisis in time and in his life that Furtwängler may have felt more deeply and threateningly than others. He provided subtitles for individual movements, ranging from “Disaster,” “Under compulsion to life,” to “Beyond” for the first three movements. The fourth movement, which still occupied him in the year of his death, carries the title “The conflict continues.” It is a confessional work, with Furtwängler explaining, “With this work I wanted to make neither a mystical and mathematical construction nor an ironic and skeptical consideration of the time, but nothing more and nothing less than a tragedy. I am not a Romantic and not a classic—but I mean what I say.”

Furtwängler was not able to perform his last symphonic work, and the posthumous premiere of the three-movement version took place in 1956, with the complete four-movement version appearing only several years later. It is a monumental work of the broad dimension of a Bruckner symphony, “yet belonging to a much starker world than Bruckner or Brahms had known.” With great Mahlerian intensity, the opening movement unfolds in a great tragic arch, a mood continued in the somber “Allegro.” The thematically related third movement moves straight into a gloomy Finale that speaks “the language of Buckner, exposes the mood of Mahler, and offers an occasional glance towards Furtwängler’s contemporary Richard Strauss.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Wilhelm Furtwängler: Symphony No. 3 in C-sharp minor (RTBF Symphony Orchestra; Alfred Walter, cond.)