The premiere of Max Reger’s Piano Concerto in F minor, Op. 114 took place at the Leipzig Gewandhaus on 15 December 1910. The soloist was Frieda Kwast-Hodapp, and Arthur Nikisch led the Gewandhaus Orchestra. The reviews were devastating, as was usually the case with Reger’s music at the time. One critic called it the “latest miscarriage of the Reger muse as she sinks deeper and deeper into inbreeding.”

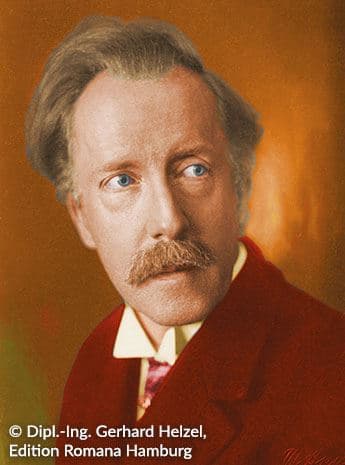

Max Reger

Reger wrote to the pianist just a couple of years later, “my Piano Concerto is going to be misunderstood for years… The musical language is too austere and too serious; it is so to speak, a pendant to Brahms’ D-minor Piano Concerto. The public will need some time to get used to it.”

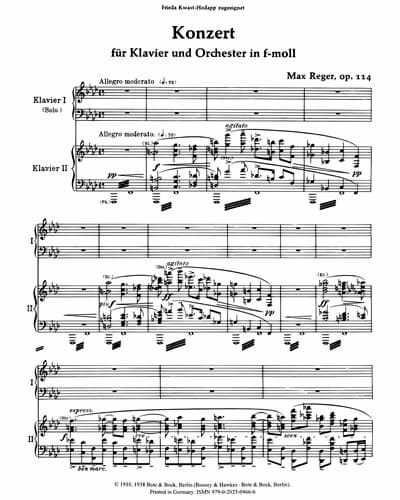

Max Reger: Piano Concerto in F minor, Op. 114 “Allegro moderato” (Markus Becker, piano; North German Radio Philharmonic Orchestra; Joshua Weilerstein, cond.)

Backstory

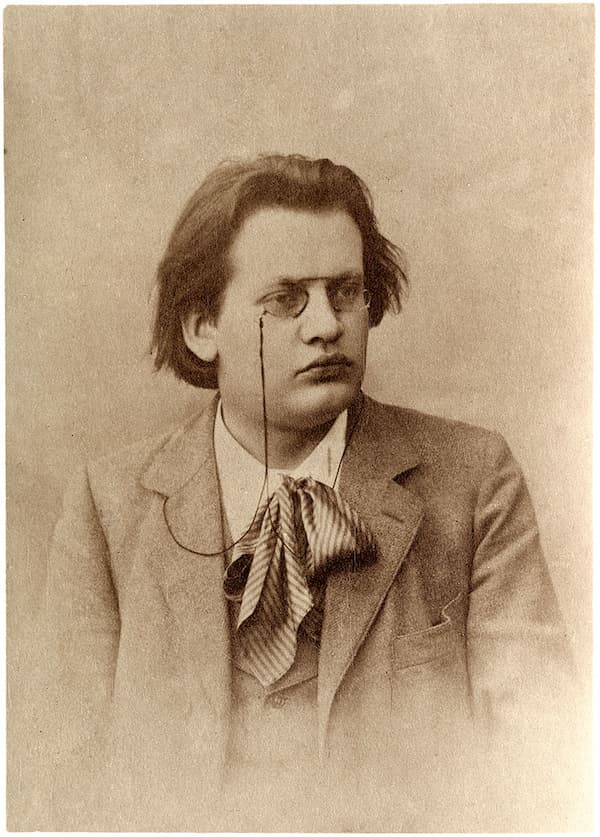

Walter Niemann

In fact, the public or critics never got used to the work at all. As a critic in 2023 wrote, “If you love music that’s cramped, monochrome, dull, and utterly charmless, then this dysfunctional piano concerto is just the ticket… some works richly deserve obscurity.”

Before exploring the reasons for such vitriol, let’s go back to the beginning. In 1910, Dortmund hosted a three-day festival entirely dedicated to the music of Max Reger. The festival covered the entire range of Reger’s output, and the pianist Frieda Kwast-Hodapp played his finger-twisting Variations and Fugue on a Theme by J S Bach, Op 81. All performers participated free of charge or at a minimal fee, and the event marked a high point in Reger’s life.

Frieda Kwast-Hodapp

Frieda Kwast-Hodapp

Yet, all was not well as various critics, most prominently the composer Walter Niemann, was up in arms against Reger’s music. In fact, Niemann was rather outspoken in his criticism of “pathological” and “sensuous” composers like Strauss, Mahler, and Schoenberg. Reger actually filed a libel suit against Niemann in 1910 and won, but he was not able to silence his biggest detractor.

Reger was a fabulous pianist and organist, and from his early days, he had harboured thoughts of writing a piano concerto. Nothing concrete ever emerged, but he found in Frieda Kwast-Hodapp “a swashbuckling and fearless soloist.” She had been a most remarkably gifted student at the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt, and she defeated Wilhelm Backhaus in the competition for the prestigious Mendelssohn Prize. She quickly established international recognition and became a celebrated pianist throughout Europe.

Max Reger: Piano Concerto in F minor, Op. 114 “Largo con gran espressione” (Marc-André Hamelin, piano; Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra; Ilan Volkov, cond.)

The Music

Max Reger’s Piano Concerto

Reger had promised Kwast-Hodapp a concerto as early as 1906, and he renewed his promise in 1910. Just days after returning from the Festival, he was drafting the first movement, quickly added the second, and wrote the finale in a mere seven days. Apparently, the autograph score, which was destroyed in 1943, bore an inscription to Kwast-Hodapp, “This beastly stuff belongs to Frau Kwast. The Chief Pig, Max Reger, confirms it.”

Reger took his pianistic influences from Brahms and Liszt. The influence of Brahms is evident in the highly technical demands of the piano part, which, nevertheless, avoids all signs of overt virtuosity. The piano is integrated into the musical structure and creates rich tonal colours. Meanwhile, Liszt’s influence appears in the contrasting textures, from powerful chords to delicate passages. Reger blends these influences to create a unique style that emphasises keyboard skills without undermining the music’s serious nature.

Reaction and Consequence

Max Reger, 1896

Reger was keen to play down the difficulties of the piano part in his letter to his publisher, and he argued that “all three movements of this concerto were composed in a strictly Classical form.” To be sure, everything is thematically structured, and the second movement included quotations from three chorales.

Two years after the premiere, Reger was still bitter about the critical reaction and he writes, “It’s really very funny that the German critics yet again are baffled when faced with my Piano Concerto. The chorale appears note-for-note as the principal melody in the Largo, and none of those donkeys noticed.” The scholar Walter Frisch writes, “Reger was proud of his Piano Concerto and claimed that he had found a path that is more likely to lead to a goal than all the other great paths.”

The story does not end well, however, as Reger, soon after the premiere, found solace in alcohol. As a friend reports, “Reger drinks particularly eagerly. At home, his wife watches him on a concert tour, and he feels free…Reger sat in his room drinking cognac, he was no longer in plain human regions.” Reger died of a heart attack in 1916, and his piano concerto is still shunned. When Alfred Brendel was asked about playing Reger’s piano concerto or dying, he replied, “I’ve always thought I’d prefer to die.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Max Reger: Piano Concerto in F minor, Op. 114 “Allegretto con spirito” (Michael Korstick, piano; Munich Radio Orchestra; Ulf Schirmer, cond.)