Sándor Veress: Piano Trio, “3 Quadri”

The three 17th-century painters, Claude Lorrain, Nicolas Poussin, and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, were all inspiration to Hungarian-Swiss composer Sándor Veress (1907 – 1992) for his 1963 piano trio.

Sándor Veress in Bern, ca. 1960 (Photo by Christian Moser)

From Claude Lorrain (ca 1600-1682), he took the idea of landscape. Lorrain, a French painter, concentrated on the idea of landscape where Mother Nature overwhelms and humans are tiny figures. The focus is not on humanity but rather on the life that surrounds him.

Lorrain studied in Italy before returning to the north. His landscape studies were done in France, Italy, and Bavaria, with his first landscape being dated 1629. Commission from the French ambassador in Rome, the King of Spain and Pope Urban VIII secured his reputation, and many more commissions followed.

Landscape as a genre was a speciality of Italian painters. Initially, landscapes were part of larger works, such as frescos. If you look at a painting such as the Mona Lisa, she sits in a chair but has an extensive landscape with roads, hills, bridges, and water behind her.

da Vinci: Mona Lisa, 1503–1506 (Louvre Museum)

In Lorrain’s work, the proportion and scale are reversed: the landscape dominates the scene, and humans are secondary.

Lorrain: Landscape with a Piping Shepherd, c. 1629–1632 (Norton Simon Museum)

Now the figure of the shepherd is secondary to the looming forest and faraway mountains.

Sándor Veress based the first movement of his piano trio on a typical landscape painting by Claude Lorrain that depicts a harbour scene in Antiquity in which the rays of the sun afford a melancholy magic to everything. There are a couple of Lorrain paintings that could meet this description, such as his 1639 work Seaport at sunset,

Lorrain: Seaport at Sunset, 1639 (Louvre Museum)

or his work from 10 years later, The Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba.

Lorrain: The Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba, 1648 (London: National Gallery)

In his work, Veress picks up on the melancholy nature of the sunset. In his writing, Veress starts with a few motivic cells that he continues to change. Instead of a brilliant Allegro opening, we have a slower Andante movement. It’s lyrical and transparent, with a couple of exceptions in the middle for an energetic outbreak.

Sándor Veress: Piano Trio, “3 Quadri” – I. Paysage de Claude Lorrain: Con moto (Absolut Trio)

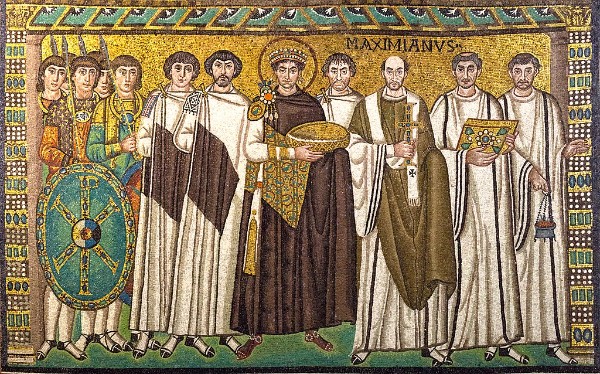

Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) was one of the leading French Baroque painters, generally on religious or mythological subjects. His work from 1637 and 1638 is known variously as Et in Arcadia ego or Les bergers d’Arcadie or The Arcadian Shepherds. Three shepherds and a woman gather around a tomb in a landscape. The tomb says ‘Et in Arcadia ego’, variously meaning ‘Even in Arcadia, there am I’; ‘Also in Arcadia am I’; or ‘I too was in Arcadia’.

Poussin: Et in Arcadia ego, 1637–1638 (Louvre Museum)

The inscription comes from Virgil’s Eclogues and, as taken up by the Italian poet Jacopo Sannazaro, it came to be a remembrance of Arcadia as a lost world of idyllic bliss. The ‘ego’ (I) in the inscription was understood to refer to Death. Even in a place of perfection, Death has a place. As the three shepherds examine the tomb, one can trace the inscription’s letters or his own shadow. Traditionally, a shadow on a tomb is a symbol of death (in other paintings, it’s represented by a skull), and in a larger metaphorical sense, art becomes the response to human beings’ inescapable mortality.

Later interpretations of Et in Arcadia ego change it from a reflection of death to a reminder from the past that in Arcadia, the dead man, too, was happy, just as are the modern dwellers in Arcadia, the shepherds.

Veress takes us to a dry and cold land where the past is too present. The music appears in melodic arches, with the primary interest in the violin and cello lines, which are sometimes presented as mirror images. The piano has only a supporting role, keeping up the melodic arches.

Sándor Veress: Piano Trio, “3 Quadri” – II. Et in arcadi ego: Quieto (Absolut Trio)

The final movement is based on The Peasant Dance by Pieter Brueghel the Elder.

Pieter Brueghel the Elder: The Peasant Dance, 1568 (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum)

The Peasant Dance was painted at about the same time as The Peasant Wedding.

Pieter Brueghel the Elder: The Peasant Wedding, 1568 (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum)

They illustrate peasant life but at the same time carry a moral message. In The Peasant Dance, the deadly sins of Glutton, Lust, and Anger come to the fore. The man seated next to the bagpiper has the symbol of vanity and pride in his hat: a peacock feather. The cause of the dance is the village’s saint’s day (St. George), but the prominence of the tavern tells us a different story. The dancers not only turn their back on the church but also on the portrait of the Virgin Mary hanging on the tree.

The peasants are depicted in a rough manner, shown to be unrefined and primitive in their approach to life. From their expressions to their teeth, they are hard-living. A man-made object, the handle from a jug, lies broken in the pathway and nature, represented by the birds, has fled to the safety of the rooftop. The pipes on the bagpipe are absurdly long, and a modern version, based on this one, shortens the chanter pipes.

Fritz Heller: Modern Renaissance model based on Bruegel’s painting

In his music, Veress gives us the sound of the country dance. It’s very much like Stravinsky’s A Soldier’s Tale in its use of irregular metre and its complex counterpoint.

Sándor Veress: Piano Trio, “3 Quadri” – III. Der Bauerntanz (Danza contadina): Tempo giusto (Absolut Trio)

Veress is considered to be one of the most important Hungarian composers in general, following Bartók and Kodály. He started his compositions with phrases from Hungarian folk songs, which, when combined with a contrapuntal style from Italian vocal polyphony, led to a modern style that uniquely combines 12-tone composition based on a tonal centre, not on a central harmonic. His students in Hungary included some of the most significant 20th-century composers, including György Ligeti and György Kurtág in Hungary and Heinz Holliger in Switzerland, where he moved in 1949.

Veress’ piano trio, Three Pictures (3 Quadri), takes images from 300 and 400 years earlier and presents them in the sound of the modern day. He’s skilful in capturing the colours and feelings (melancholy or shadowy) of the paintings as well as making his own commentary on something like the peasants in the Bruegel work.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter