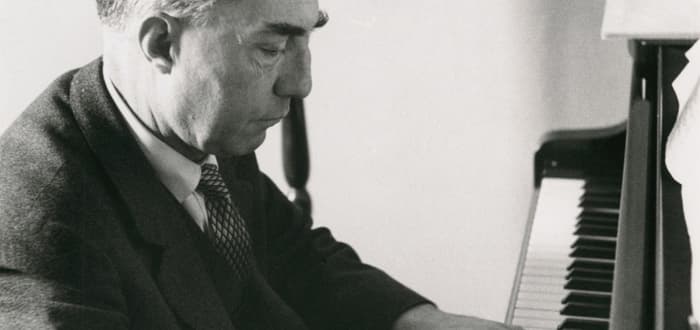

Johann Strauss II was one of Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s (1897-1957) musical idols. Korngold possessed considerable knowledge of the Waltz King’s works as he had arranged for the Theater an der Wien new performing versions of Nacht in Venedig, Cagliostro in Wien, Fledermaus, Waltzer aus Wien and Lied der Liebe. Korngold was also a close friend and frequent guest at the salon of the composer’s widow Adele. When an American publisher was looking for new music suitable for school orchestra in 1953, Korngold fashioned a brilliant score in three parts based on little-known melodies by Strauss.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

Titled Straussiana, Korngold refused to provide an opus number for the work, “superstitiously believing that he would not live to write beyond Opus 42.” In the event, it would nevertheless turn out to be Korngold’s last completed orchestral work. The three short movements are based on a polka originating in the operetta Fürstin Ninetta, while the Mazurka is based on a Polka from Cagliostro in Wien. The concluding waltz comes from the operetta Ritter Pásmán, one of the Waltz King’s biggest failures. “In this work, Korngold embellished Strauss’s original orchestrations with sparkling percussion and the addition of harp and piano.”

Erich Wolfgang Korngold: Straussiana (Swiss Romande Orchestra; Kazuki Yamada, cond.)

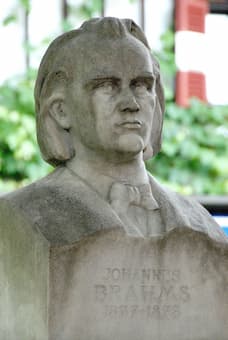

Composer, pianist, and conductor Robert Chumbley believes that “writing for piano developed alongside piano technology from Beethoven to Chopin to Liszt, with Brahms’ music being the apogee of tonal exploitation of the modern piano.”

Robert Chumbley

Given such high praise for Johannes Brahms, it is not surprising that Chumbley wrote a number of major works inspired by this composer. Brahmsiana I is a ballet score for orchestra commissioned by the Atlanta Ballet, while Brahmsiana II is based on Brahms’ Op. 117. “There are no direct musical quotes from Op. 117,” Chumbley explains, “but rather, I looked at their form and textures, rhythms, and their juxtaposition of the lyrical and the forceful.” This tribute explores the many sonorities associated with Brahms, from wide-spaced textures between deep bass and high treble, intricate voice leading, and counterpoint to unabashed lyricism. The polytonal harmony is closer to the 21st century than to Brahms, with its contemporary musical language particularly evident during the central Scherzo.

Robert Chumbley: Brahmsiana II (Steven Masi, piano)

In 1955, Luigi Dallapiccola (1904-1975) was once again approached by the violinist Sandro Materassi with a request for further work along the lines of the 1951 Tartiniana. That particular divertissement was derived from various movements of unpublished violin concertos by Tartini. When Materassi returned from a visit to Padua in 1955 armed with a bundle of photocopies of music manuscripts by Tartini, he asked Dallapiccola whether he could do something with them.

Luigi Dallapiccola

Dallapiccola went to work and composed two versions of Tartiniana seconda, one for violin and piano and the other for violin and chamber orchestra. Incorporation of English horn, celesta, glockenspiel, vibraphone, side drum, and cymbals imbued the second version with a bright and almost playful sonority. The four movements of the work do not fundamentally alter the Tartini originals but draw from them various contrapuntal possibilities. The opening “Pastorale” evokes a mood of graceful yearning, and is followed by a muscular “Tempo di Bourrée.” A virtuoso “Presto” prepares for a Variation movement announced by the commanding theme.

Luigi Dallapiccola: Tartiniana seconda (Alberto Bologni, violin; Giuseppe Bruno, piano)

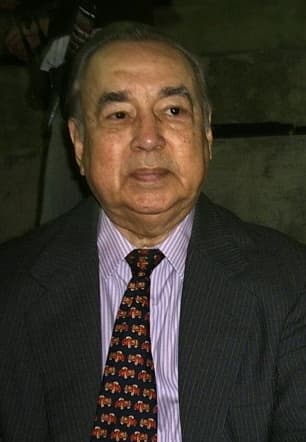

The Venezuelan pianist and composer Aldemaro Romero (1928-2007) created a wide range of music, including works for orchestra, orchestra and soloist, orchestra and choir, chamber music, and symphonic works of great breath. He collaborated with such diverse artists as Charlie Byrd, Dean Martin, Stan Kenton, Tito Puente, and recorded on the RCA label. Eagerly promoting Latin American music abroad, he was awarded the Moscow Cinema Festival Peace Prize in 1969, and he founded the Caracas Philharmonic Orchestra.

Aldemaro Romero

As one of the founders of Venezuela’s “onda nueva style,” which followed on the heels of the Brazilian “bossa nova and the Venezuelan “joropo,” Romero was known for his ability to mix popular songs and folk elements with classical forms and techniques. And such is the case in his Tocatta Bachiana-Pajarillo Aldemaroso. Clear allusions to Bach’s famous D-minor Toccata are blended with a typical Venezuelan dance, the “pajarillo.” It is like a waltz, but with the accent on the weak beat. The pajarillo takes over the melody and rhythm and provides a sense of improvisation and contrast to the formal sections of the toccata.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Aldemaro Romero: Tocatta Bachiana-Pajarillo Aldemaroso (Venezuela Symphony Orchestra; Theodore Kuchar, cond.)