While clearing out my piano room ahead of a house move last year, I came upon a box of old concert programmes, some dating back twenty-odd years. Some were dog-eared and scuffed, or covered in scribbled notes from when I was a regular concert reviewer; others were pristine, as if unopened. One bore the signature in thick black felt-tipped pen of the tenor Ian Bostridge. I didn’t even have to open the programme to recall that concert – Bostridge singing Schubert’s heartbreaking song cycle Winterreise, accompanied by Mitsuko Uchida, in an emotionally profound performance which was moving and memorable to this day.

While clearing out my piano room ahead of a house move last year, I came upon a box of old concert programmes, some dating back twenty-odd years. Some were dog-eared and scuffed, or covered in scribbled notes from when I was a regular concert reviewer; others were pristine, as if unopened. One bore the signature in thick black felt-tipped pen of the tenor Ian Bostridge. I didn’t even have to open the programme to recall that concert – Bostridge singing Schubert’s heartbreaking song cycle Winterreise, accompanied by Mitsuko Uchida, in an emotionally profound performance which was moving and memorable to this day.

Schubert: Winterreise, Op. 89, D. 911 – No. 11. Fruhlingstraum (Bostridge)

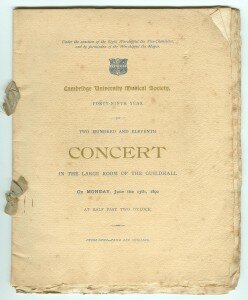

Printed programmes hold memories within them – of concerts, music, artists. While the prime purpose of the programme is to give audiences details of the music being played, translations of song texts, and information about the performers, a programme is also a significant souvenir of an event.

Brahms: Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 77 – III. Allegro giocoso, ma non troppo vivace – Poco più presto (Haendel)

My parents used to keep all the programmes of concerts they attended and this represented quite a significant record of concert and opera-going. They were kept in a special trunk in the box room and I used to love leafing through them. They had a distinct smell, like the musty reminiscence of a second-hand bookshop. Here amongst those age-speckled pages were the “greats” from an earlier era – Daniel Barenboim and Jacqueline du Pré, Itzhak Perlman and Pinchas Zuckerman, Ida Haendel, John Ogdon, Gervase de Peyer, James Galway and many others, some of whom are fortunately still with us and still making music.

Bach: Flute Sonata in E-Flat Major, BWV 1031: II. Siciliano (James Galway)

As a child I found the printed programme a curious, esoteric document, full of complex, often foreign words and concepts. I liked looking at the pictures of the soloists or conductors, many of whom had artistically wild hair (conductor Louis Frémaux, for example, who worked with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra in the 1970s in the era before another, younger wild-haired man took over), but the programme notes were largely incomprehensible to me. When my musical studies were more advanced, I was better able to decipher programme notes: I understood terms like Ternary Form, Rondo or Coda, but still the notes seemed to inhabit a rarefied world of musicology which only a select few could enter. Fortunately today, programme notes are generally more accessible and written to engage the reader/listener.

Modern technology has allowed for some innovations in concert programmes. Some organisations and venues offer the printed programme as a free download, in a reduced form, in advance of the concert, but a fistful of A4 sheets does not have the same tactile quality of a shiny programme. And that is another pleasurable aspect of the printed programme – how it feels in the hands. Some, like the BBC Proms programmes appear satisfyingly weighty (until one discovers they are mostly stuffed with adverts!), others may be a slim piece of folded card, but no less an important document of the event. Many offer tantalising enticements to future concerts. Revisiting a programme from a long-passed concert can elicit a Proustian rush of memory, of another time and place, and a record of music enjoyed and shared.

More Blogs

-

Max Steiner, the Movie Composer Injected With Amphetamines The "father of film music" who scored King Kong, Casablanca, and more

Max Steiner, the Movie Composer Injected With Amphetamines The "father of film music" who scored King Kong, Casablanca, and more - Sitkovetsky Trio: Conviviality and Mastery

The Beethoven Piano Trio Project Sitkovetsky Trio completes ambitious Beethoven piano trio project -

Which Composer Wrote the Most Symphonies Ever? The history of symphony composition and surprising prolific composers

Which Composer Wrote the Most Symphonies Ever? The history of symphony composition and surprising prolific composers - Richard Strauss’ Rosenkavalier

Top 8 Tunes of Wit and Romance Look at the most memorable musical moments from the opera

I’m moving. Found several programs from the 1930’s New York City area including Metropolitan Opera and concert pianists of the day. I don’t want to throw them away. Want to give them away. Any ideas?