Mikhail Ėmmanuilovich Goldstein (1917-1989) was a Ukrainian-born composer, violinist, conductor, musicologist, and teacher. Born into a family of mathematicians, he received his first violin lessons at the age of four and, one year later, made his recital debut. Mind you, at the age of eight, he first appeared as a soloist accompanied by a symphony orchestra.

Tomb of composer Mikhail Goldstein

Goldstein’s first teacher was no other than Pyotr Stolyarsky, the teacher of Milstein and Oistrakh, and he entered the Moscow Conservatory aged 13, studying the violin with Yampolsky, conducting with Saradzhev and composition with Myaskovsky. An injury to his left hand prevented an extensive performing career, and Goldstein turned to teaching and composing.

Mikhail Goldstein: Symphony No. 21 (attr. Ovsianiko-Kulikovsky) “Allegro”

The Great Hoax

Goldstein did compose a number of works, including a number of string quartets, but he is probably best known as the discoverer of Symphony No. 21 in G minor, written “for the dedication of the Odessa Theatre 1809.” The composer N.D. Ovsianiko-Kulikovsky (1768–1846), a landowner who presented his serf orchestra at the Odessa Theatre in 1810, was an actual historical figure. However, the composition was a complete hoax.

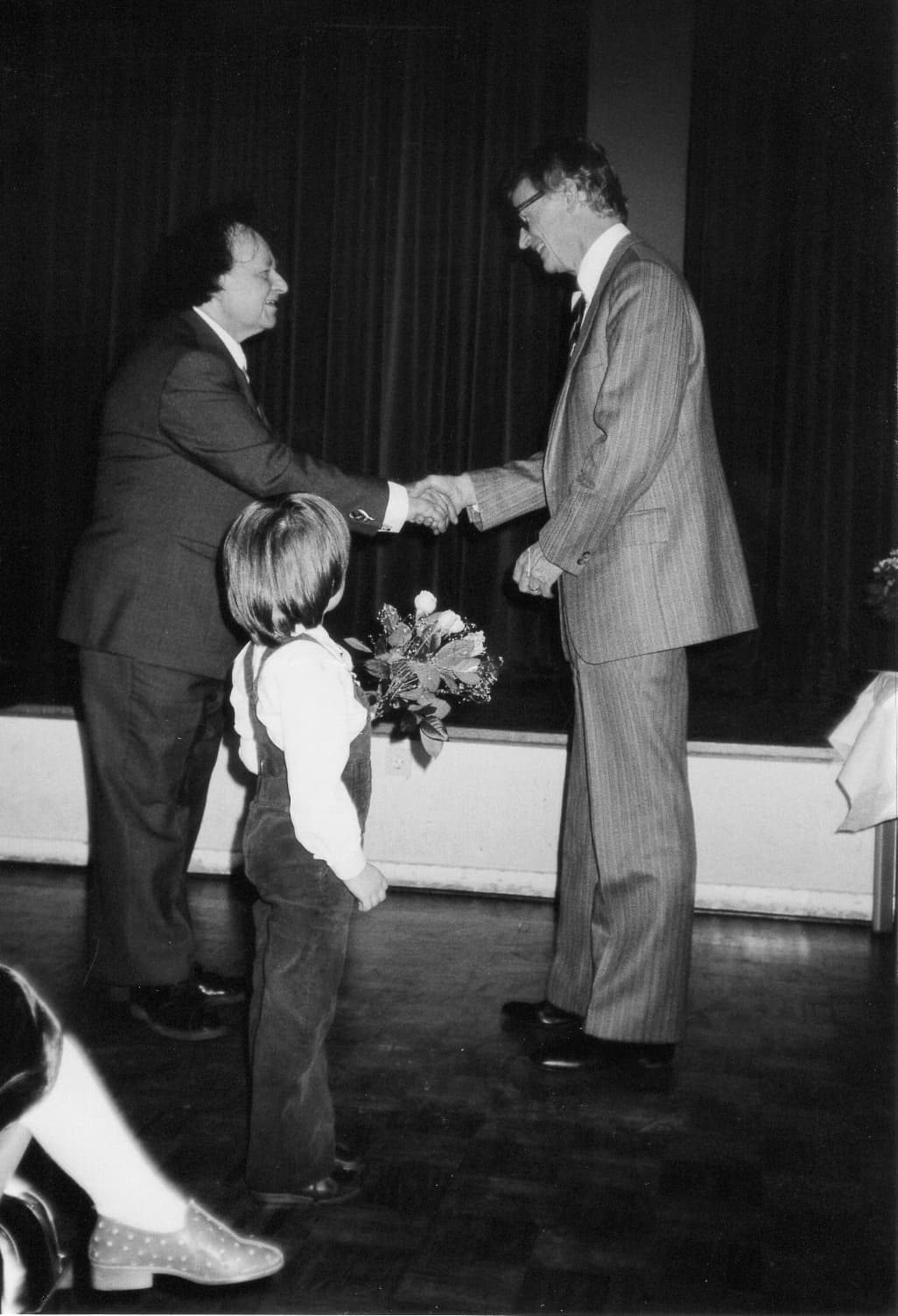

Mikhail Goldstein and Carl Malsch

Goldstein himself had written the work in response to a critic who claimed that Goldstein would never understand Ukrainian music because he was Jewish. In secret, Goldstein composed the work and deposited it in the archives of the Odessa Conservatory. The score was rightfully discovered by Goldstein in 1948, and it became a Soviet sensation. Here was proof that the Russian Empire had produced a work of high quality during the time of Haydn. Nobody questioned the authenticity of the work, and it was performed in 1949, published in 1951, recorded by Mravinsky, and made the subject of at least two dissertations.

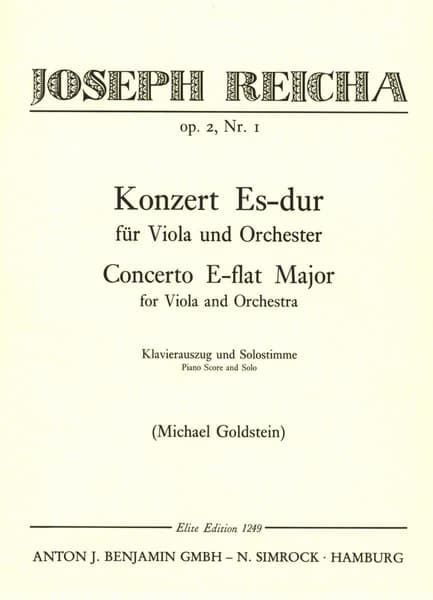

Mikhail Goldstein: Concerto for Viola (attr. Joseph Reicha)

The Reicha Hoax

When Goldstein admitted the hoax, a criminal case was initiated against him by the investigative bodies of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs in 1957. There was great embarrassment all around, and the party tried to keep matters away from public discourse for a long time. In a typical case of saving face, it was claimed that neither Goldstein nor Ovsianiko-Kulikovsky could have composed the work, and believe it or not, the controversy over the extent of the fabrication has not been satisfactorily resolved even today.

The Goldstein Reicha Concerto

While nobody had ever heard of Ovsianiko-Kulikovsky in musical circles, the same can’t be said of Joseph Reicha (1752-1795). He was a Czech cellist, composer, and conductor whose uncle was none other than the music theorist Anton Reicha. He personally knew Beethoven, and his compositions were admired by Leopold Mozart and Michael Haydn. And to everybody’s surprise, Mikhail Goldstein found a completely unknown Viola Concerto by Joseph Reicha in a dusty old library. Well, you might have rightly guessed by now that Goldstein was actually the composer of this “long lost masterwork.”

Mikhail Goldstein: Viola Concerto in C Major (attr. Ivan Khandoshkin) (Rudolf Barshai, viola; Moscow Chamber Orchestra; Rudolf Barshai, cond.)

The Khandoshkin Deception

Goldstein emigrated to East Germany in 1964 and from there, moved to Israel (1967) before settling in Hamburg (1969), where he joined the staff of the Hochschule für Musik. He also taught at the Menuhin School in England and at the Musashino Academia Musicae in Tokyo. Goldstein had a serious talent for finding unknown masterworks, and one such composition was attributed to Ivan Khandoshkin (1747-1804), who was considered the “finest Russian violinist of the 18th century.”

Actually, Khandoshkin was of Ukrainian Cossack origin, and his father was a professional French horn and percussion player in the court orchestra of Tsar Peter III. Ivan held a position at the Yekaterinoslav Musical Academy, and he composed six violin sonatas and several variation cycles based on folk songs. His Viola Concerto was supposedly written in 1801 and first published by the State Publishing House in Moscow in 1947. It was recorded on the Melodya label with Rudolf Barshai as soloist and conductor of the Moscow Chamber Orchestra. And once again, Goldstein was actually the composer.

Mikhail Goldstein: Expromt for violin and piano, (attr. Balakirev) (Yury Revich, violin; Valentina Babor, piano)

The Balakirev Mystification

Ovsianiko-Kulikovsky

Goldstein wrote a number of articles on Russian, Ukrainian, and German composers, and he also served on the editorial staff of the Riemann Musik Lexicon. He also published music and articles under the pseudonym Mykhajlo Mykhajlowsky, and his memoirs were published in Frankfurt. Besides the Balakirev mystification, Goldstein also composed a sonata attributed to Giuseppe Tartini, and an “Albumblatt” attributed to Alexander Glasunow.

Goldstein’s life and professional slogan was: “Music helps to cross state borders.” In 1984, he was awarded the German Order of the Cross of Merit for his musical and pedagogical work and social activism in support of immigrants and the disabled. Goldstein was greatly admired by the composer and pianist Jean Françaix, who dedicated his Tema con 8 variazioni for solo violin to this wonderful musical jester.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Jean Françaix: Tema con 8 variazioni (Barbora Kolářová, violin)