“It was as if I had been born anew”

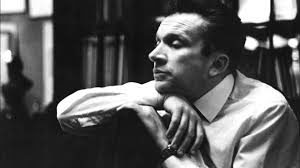

Mieczysław Weinberg

Prokofiev and Shostakovich are household names in 20th century Russian music, but until recently hardly anybody recognized the name Mieczysław Weinberg (1919-1996). Born in Poland but forced to flee his homeland ahead of invading German forces in 1939, he immigrated to Russia and was subject to discrimination and the constant threat of arrest under Stalin. Although working in the shadow of his close friend Dimitri Shostakovich, Weinberg enjoyed considerable success in his adopted country. His extensive catalogue of works—including 26 complete symphonies, 17 string quartets, 28 instrumental sonatas, 7 operas and roughly 40 film and animation scores—were taken up and recorded by Russia’s foremost performers and conductors. However, his works were only known and accessible in the USSR. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Weinberg’s music slowly arrived on the international stage, and we gradually discovered a treasure drove of musical expressions of immense significance. As one scholar wrote, “from film and circus music to tragic grand opera, from simple melodies with easy accompaniments to complex twelve-tone music, Weinberg was a master of all forms, genres and stylistic directions.” In fact, it has been argued that the triumvirate Prokofiev, Shostakovich and Weinberg, composed the greatest Russian music of the 20th century.

Mieczysław Weinberg: Piano Quintet, Op. 18

Weinberg and Shostakovich

Mieczysław Weinberg was born in Warsaw one hundred years ago, and he started writing music in his early childhood. By the age of ten, he played the piano in the Yiddish theatre operated by his father, and only two years later entered the Warsaw Conservatory. His pianistic talents were well known, and it was assumed that he would become a touring virtuoso in the tradition of Polish legends like Leopold Godowsky, Ignaz Friedman and Ignacy Paderewski. In fact, Joseph Hoffmann had arranged for the boy to study in America, but invading German troops in 1939 brutally crushed that plan. Weinberg set off on foot, heading east, and he would never see any member of his family again. Weinberg continued his studies at the Minsk Conservatory, but one day after his final examination in June 1941, the Wehrmacht rolled into Russia and Weinberg was forced to flee again. Together with many intellectuals and artists, Weinberg was relocated to eastern Uzbekistan, and the city of Tashkent. He found work in the Tashkent opera house, and he married the daughter of the illustrious actor and theatre director Solomon Mikhoels. He also met Shostakovich and reported, “It was as if I had been born anew… Although I took no lessons from him, he was the first person to whom I would show each of my new works.”

Mieczysław Weinberg: Symphony No. 1, Op. 10

Shostakovich organized for Weinberg to come to Moscow, and he worked as a freelance composer and pianist. Since he never became a party member, Weinberg was without the protection of the state. Becoming part of Soviet intelligentsia was clearly fraught with severe dangers. In 1948 his father-in-law was murdered by the Soviet secret police, and Weinberg was placed under surveillance. He was arrested in 1953 and charged with “making propaganda for the establishment of a Jewish state in the Crimea.” He spent three month in prison and was saved from execution by a letter Shostakovich wrote in his defense. Stalin’s death finally provided some measure of personal and artistic freedom, and Weinberg’s compositions would become an act of atonement. Weinberg lost almost his entire family in the war, including his parents and sister who were murdered at the Trawniki camp outside Warsaw. He contemplated the horrors of the suffering of the Jews and the loss of children in many of his works, and once wrote, “Many of my works are related to the theme of war. This, alas, was not my own choice. It was dictated by my fate, by the tragic fate of my relatives. I regard it as my moral duty to write about the war, about the horrors that befell mankind in our century.”

In the 1950s and early 1960s, renowned instrumentalists and conductors took up Weinberg’s compositions. However, the composer remained an outsider. Foreign born and speaking with a heavy accent, the regime was ever suspicious. Weinberg earned a living writing scores for film, for the circus and for children. And he eventually set to work on an opera with a libretto by a concentration-camp survivor, with a scene set in Auschwitz. The Passenger was completed in 1968 but it had to wait for its first full staging until 2010. Weinberg remained relentlessly prolific, and his output increased unabated during the last two decades of his life. Weinberg was described as a very modest person, and an extremely subtle and delicate composer. “His music breathes a beauty and warmth that is seldom found among contemporary classical works; yet, upon hearing the music, one is also impressed by an intrinsic power, a certain tactile strength and a dynamic, forward-driving motion.” Weinberg suffered from Crohn’s disease for the last three years of his life, and he converted to Orthodox Christianity less than two months before his death in Moscow in January 1996.

It was too hard for him to remain a Jew. The Nazis led him to abandon his family, and the God of Israel led him to abandon the religion of his birth. But for Shostakovich he might never have made it so successfully into the 21st century.

His conversion wasn’t voluntary – acoording to his daughter, he was baptized at the instigation of his second wife when he was old and sick, and suffering from dementia.