The New Kind of Ballet ‘Coreodramma’

The cello virtuoso Luigi Boccherini came from a family of talented performers: his father, Leopoldo, was a bass player; his brother Giovanni was a ballet dancer and later a librettist for comic operas; his sisters Maria Ester and Anna Matilde were ballet dancers, and Riccarda was an opera singer.

Maria Ester, prima ballerina in Bologna, Venice, and Florence between 1763 and 1777, married the dancer and choreographer Onorato Viganò and their son, Salvatore Viganò (1769–1821) went on to international fame as a dancer and choreographer. It was his interaction with Beethoven that takes our attention. Viganò invented a new ballet style and asked Beethoven to provide the music for it.

Johann Gottfried Schadow: Salvatore Viganò

Salvatore created a new kind of ballet that he called ‘coreodramma’, highly dramatic ballets on historical, mythological, or literary themes that incorporated mime into the dance. Ballets at the time were based on what was called ‘pure dance’ or ‘dance in the French style’ – ballets in standardized and formulaic genres, such as divertissements and minuets, all of which had their appropriate and prescribed clothing and foot and hand gestures. After decades of pure dance, the style was getting mechanical. Viganò felt the limits and moved to simplify the costuming and increase the variety of gestures. He freed up the body to more expressive and rhythmic movements so that the dancing could tie itself to the psychological nuances demanded by the plot. Adding pantomime to the dance made the level of expression improve.

Viganò’s work was perfectly placed. He worked at La Scala, Milan, which had become a centre for ballet and opera. A reassessment of Shakespeare’s dramas happened in Italy at the beginning of the 19th century (this would later hit opera, first with Rossini’s Otello (1816) and then Verdi’s Macbeth (1847), Otello (1887), and Falstaff (1893)), which made his dramatic stories appropriate for Viganò’s ballet setting. And, finally, there was a demand for grand theatre, which Viganò’s ballets could supply.

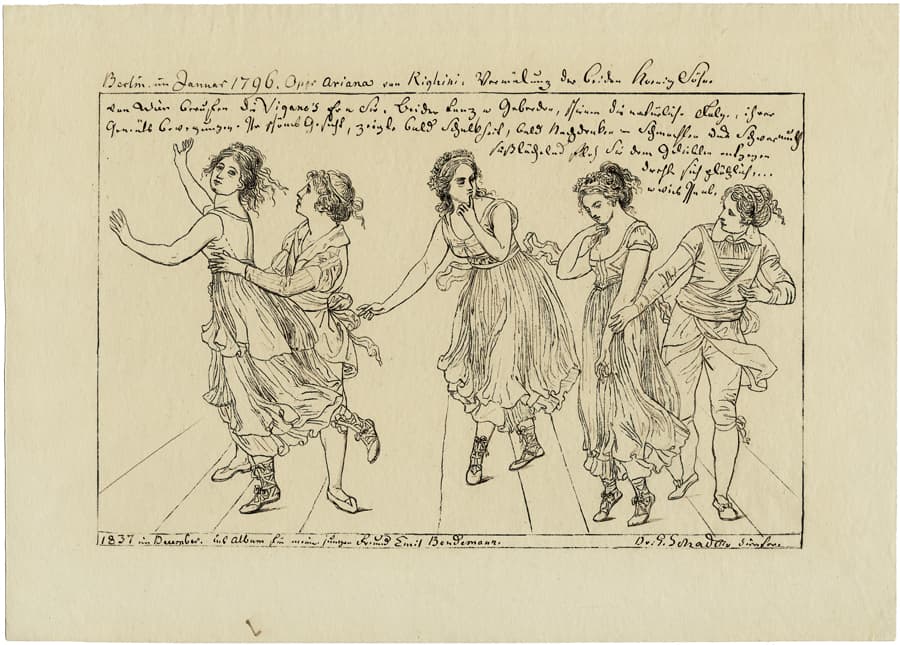

In Viganò’s vision, the wigs, masks, and elaborate clothing, such as hooped skirts, disappeared from the ballet stage, replaced by costumes that were simpler and more natural. His reforms, started in the 1790s, featured loose neo-classic dresses and either open-toe sandals or flat, flexible slippers. In an even more striking change, a happy ending to the ballet was no longer a requirement.

Johann Gottfried Schadow: Sketch for the opera Ariana by Righini (Berlin, 1796)

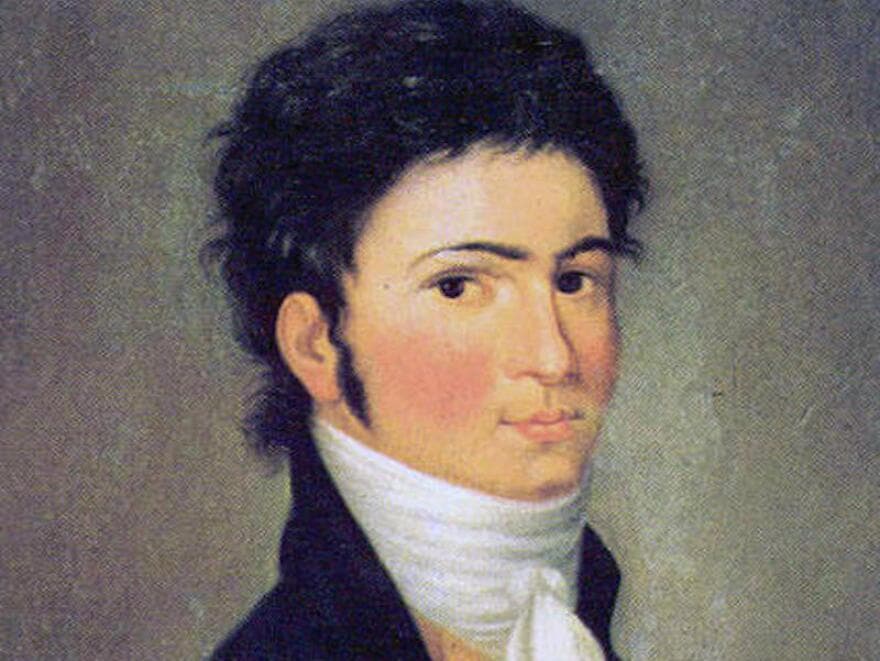

One of his first coreodrammas was created in 1801 with no less than Ludwig van Beethoven. Die Geschöpfe des Prometheus, Op. 43 (The Creatures of Prometheus). Beethoven composed an overture and 16 numbers for the ballet, creating a work that was an independent theatrical art. The ballet was given its premiere at the Burgtheater in Vienna on 28 March 1801 and was successful enough to be repeated more than 20 times.

Beethoven in 1801

Ludwig van Beethoven: Die Geschöpfe des Prometheus (The Creatures of Prometheus), Op. 43 – Overture (Freiburg Baroque Orchestra; Pablo Heras-Casado, cond.)

When Viganò took the work to Milan, he completely revised it, including replacing the composer. Beethoven’s music was replaced by music by Haydn, Mozart, and Viganò himself. The new ballet, now entitled simply Prometheus, had its premiere on 22 May 1813. Prometheus had a new plot that had been revised and expanded, more characters, and extensive use of stage machinery. It was an enormous production: ‘The stage was animated by 13 primi ballerini, 38 different characters who acted the chorus, plus 80 other ballet dancers who appeared at the beginning of the first and second act, representing, respectively the age of the brutes, the origin of mankind, and the wonders of heaven.’ The work was an immediate success, being given more than 40 times in that season alone.

After a very complicated story of Prometheus stealing the fire of the gods, and educating the nascent humans on the importance of mind and emotion, we then progress to Love, War, Drinking, and Death. Salvatore Viganò danced the role of the human man and, at the end of the opera, gets his solo before the final wedding.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Die Geschöpfe des Prometheus (The Creatures of Prometheus), Op. 43 – Act II: Coro e Solo di Viganò: Andantino – Adagio – Allegro (Melbourne Symphony Orchestra; Michael Halász, cond.)

We know what this did for Viganò’s career, but what did this do for Beethoven? One historian noted that Beethoven’s music for the ballet was lighter and easier than his normal concert music. We can see ‘Beethoven exploiting instruments and coloristic orchestral effects that would never appear in his symphonies or serious dramatic overtures.’ One example of this was his choice of instruments. Both the harp and the basset horn are used here, which normally were not in his usual orchestras.

This coreodrama was the beginning of Romantic ballet and Beethoven was there at the start.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter