Creations Inspired by Characters in Wagner’s Siegfied, Tristan und Isolde and Ring Cycle

For the artists and followers of Decadence in late–19th century London, Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was their composer of choice. The artist Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898) was a devoted follower of Wagner, collecting not only Wagner’s essays, scores, and librettos but also biographies and criticisms of him. In the months leading up to his death at age 25 from tuberculosis, Beardsley specified that Wagner’s prose works should not be included in the sale of his library. The English critic Gleeson White wrote after Beardsley’s death of seeing him at a performance of Tristan: ‘those transparent hands clutching the rail in front, and thrilling with the emotion of the music, was in itself a marvellous experience. No instrument in the orchestra vibrated more instantly in accord with the changes of the music, from love-passion to despair’.

One of the first Wagner characters Beardsley created was the triumphant young Siegfried, seen just after having killed the dragon Fafner.

Beardsley: Siegfried, Act II, 1892-93 (Victoria and Albert Museum)

Richard Wagner: Siegfried – Act II Scene 2: Siegfrieds Hornruf (Siegfried’s Horncall) – Haha! Da hätte mein Lied (Simon O’Neill, Siegfried; Falk Struckmann, Fafner; Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra; Jaap van Zweden, cond.)

Richard Wagner: Siegfried – Act II Scene 2: Wer bist du, kühner Knabe (Simon O’Neill, Siegfried; Falk Struckmann, Fafner; Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra; Jaap van Zweden, cond.)

The illustration was published in The Studio in April 1893. Unlike his later work, this drawing is very detailed and has many ‘so-called hairline calligraphic flourishes used for decorative effect’. It is very Renaissance in feeling, evoking memories of works by artists such as Andrea Mantegna. At the same time, it has the elongated figure and the ‘dense linear style’ as seen in the works of Edward Burne-Jones and other Pre-Raphaelites. Beardsley gave the drawing to Burne-Jones who hung it in his drawing room alongside prints and drawings by Albrecht Dürer – true honour, indeed, on the part of Burne-Jones.

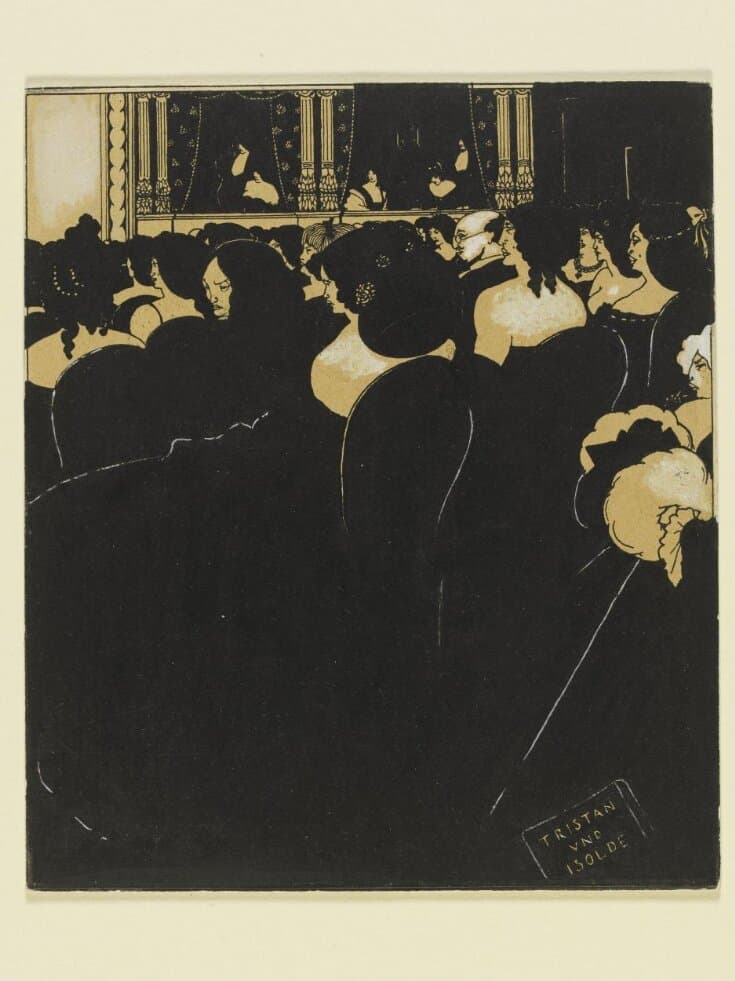

One of Beardsley’s most famous Wagner pictures shows opera goers at a production of Tristan und Isolde (as we can see from the programme book dropped on the floor).

Beardsley: The Wagnerites, 1894 (Victoria and Albert Museum)

Seated in the stalls of an opera house are a dense block of men and women, shown as stylized curves with elaborate coiffures. In the box seats are three seated women and two standing men. This picture, produced in The Yellow Book III, in October 1894, isn’t about the opera, it’s about the audience. The Beardsley expert Stephen Calloway considers this work to be ‘one of the greatest masterpieces of Beardsley’s manière noire’. The women all appear to be looking at the stage whereas the men appear to be looking in a different direction. This work, only one year after the different aesthetic of Siegfried, Act II, almost seems to be showing the unified block of Wagner-lovers. In Britain of the 1890s, Wagner was not an innocent topic. It had become its own cultural movement with adherents of musical conservatism attacking Wagner’s structure and harmonic innovations while his advocates held them up as something to be defended. As one critic noted: ‘labeling oneself a Wagnerite…was an act replete with political (in the broadest terms) resonance’. The Decadent movement found strong points of inspiration in Wagner’s portrayals of eroticism, morbidity, and suffering.

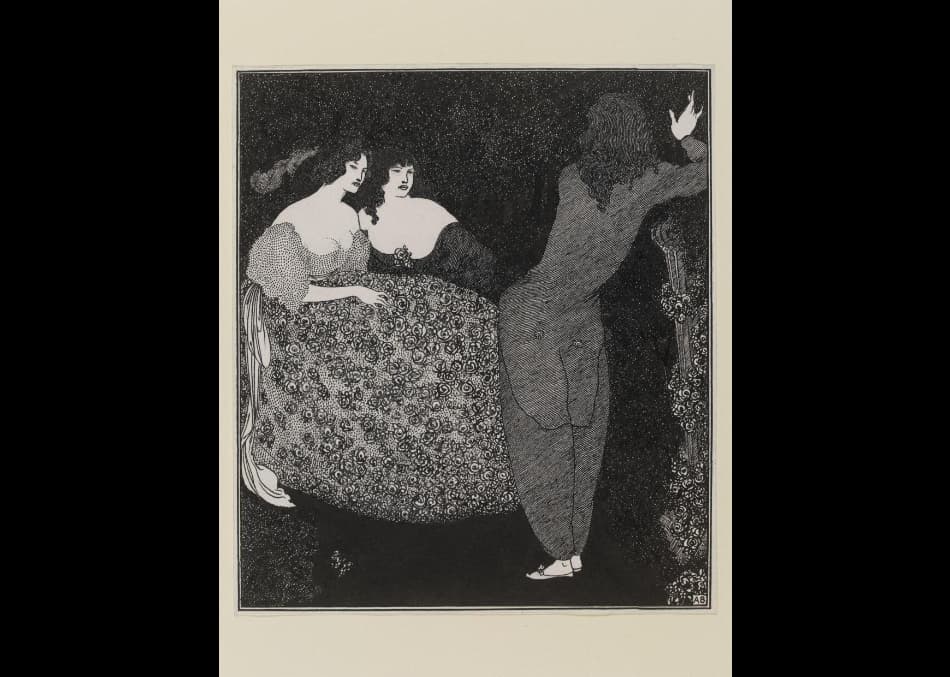

Other Beardsley Wagner illustrations include two women in a garden listening to a reading of Tristan und Isolde.

Beardsley: A Répétition of ‘Tristan und Isolde’, 1896 (Victoria and Albert Museum)

Beardsley also worked on a set of illustrations for Tristan und Isolde.

Beardsley: Design from the cover of ‘Tristan und Isolde’

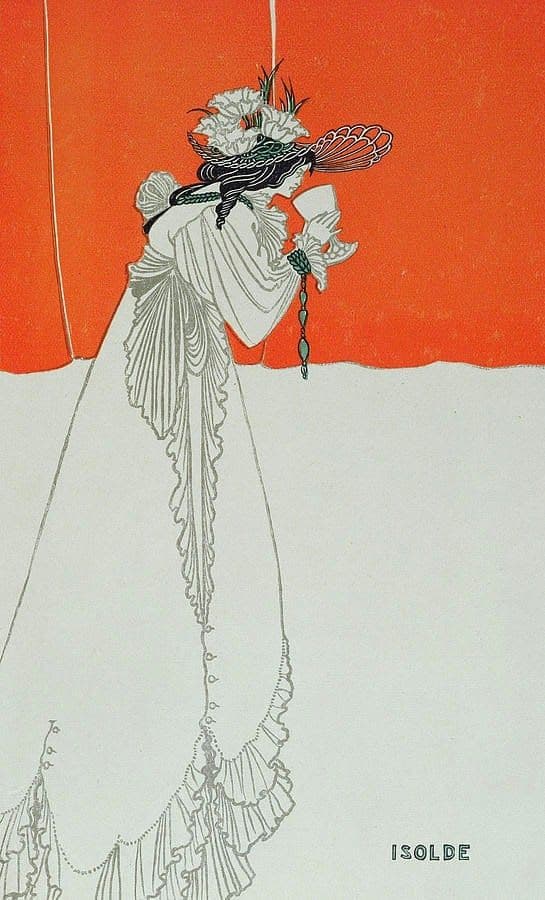

Beardsley: Isolde, 1895 (The Studio)

Richard Wagner: Tristan und Isolde – Act III Scene 3: Mild und leise wie er lächelt (Hedwig Fassbender, Isolde; Magnus Kyhle, Melot; Lennart Forsén, King Marke; Royal Swedish Opera Orchestra; Leif Segerstam, cond.)

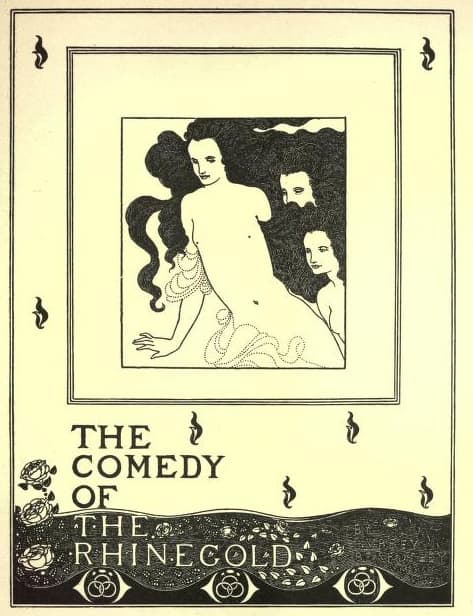

In the final issue of The Savoy, a short-lived journal (1896 only) designed to compete with The Yellow Book, four illustrations by Beardsley were printed to illustrate Das Rheingold. These appear to have only appeared in The Savoy.

Beardsley: Frontispiece to ‘The Comedy of the Rhinegold’, 1896 (The Savoy, 8)

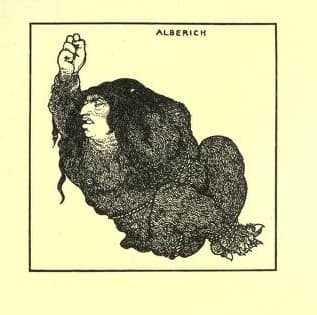

Beardsley: Alberich, 1896 (The Savoy, 8)

Richard Wagner: Das Rheingold – Scene 1: Vorspiel (Bayreuth Festival Orchestra; Christian Thielemann, cond.)

The title The Comedy of The Rhinegold isn’t explained, but Beardsley had written to his publisher Smithers informing him he was working on a book on Wagner’s story, but it was never completed.

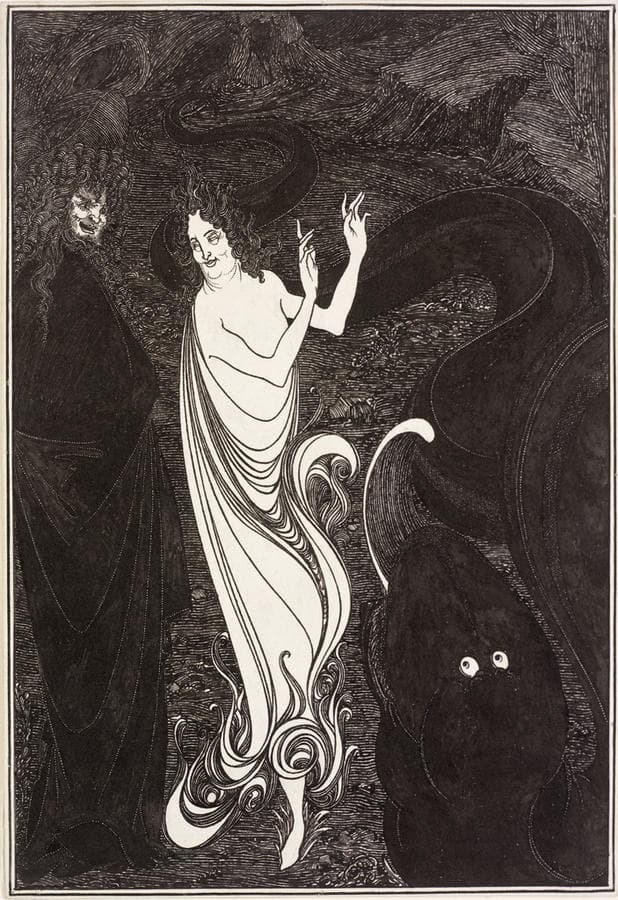

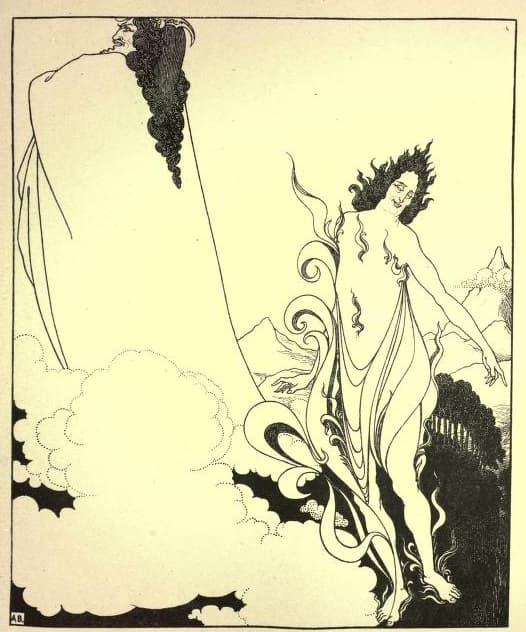

Also from Das Rheingold, Beardsley created two images of Wotan’s and Loge’s visit to the underworld of the Nibelung. The Third Tableau shows Wotan and Loge encountering Alberich as a serpent. The other was done as the outside wrapper for The Savoy, no. 6.

Beardsley: Third Tableau of Das Rheingold, 1896 (Rhode Island School of Design)

Beardsley: The Fourth Tableau of Das Rheingold, 1896 (Victoria and Albert Museum)

Richard Wagner: Das Rheingold – Scene 4: Bin ich nun frei (Andrew Shore, Alberich; Arnold Bezuyen, Loge; Albert Dohmen, Wotan; Bayreuth Festival Orchestra; Christian Thielemann, cond.)

Das Rheingold was first performed in London in the summer of 1892. Loge’s clothing of stylized flames is pure Art Nouveau.

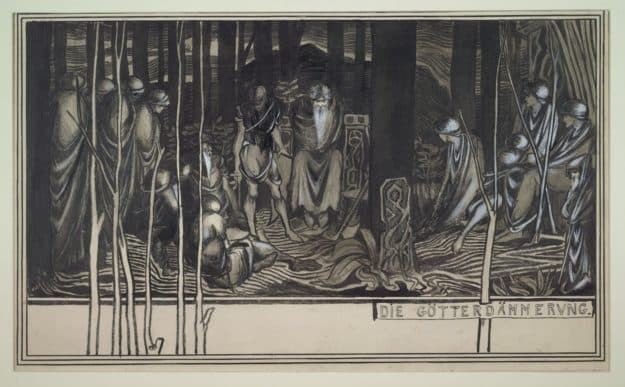

The last part of the Ring cycle, Götterdämmerung, was also illustrated by Beardsley, in an image that has rarely been seen.

Beardsley: Die Götterdämmerung, 1892 (Princeton University Library)

Richard Wagner: Götterdämmerung – Act III, Scene 3: Apotheosis (Russian State Symphony Orchestra; John McGlinn, cond.)

Beardsley’s Götterdämmerung is extraordinary in its compression of the Wagner work into one image and shows Beardsley’s knowledge of the work and the cycle as a whole. One writer described it as: ‘the gods shrouded in long drapes in a bleak forest setting; with their elongated limbs and enveloping robes they appear androgynous figures, listless and melancholy, entrapped by the sharp bare stems that rise from the border and ground around them’. The drawing is done as a horizontal image in pen and ink with Chinese white as a highlight of the hair and exposed limbs. The Rhine is rising below them, while above, with the same kind of wavering lines, the sky seems on fire.

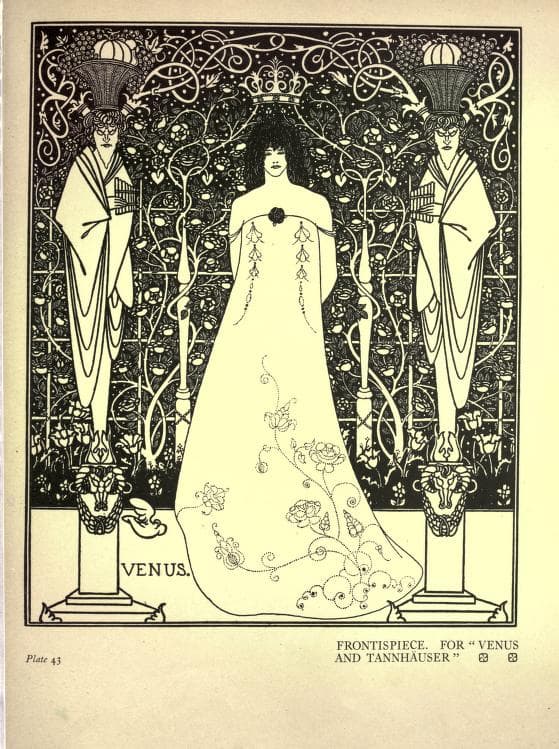

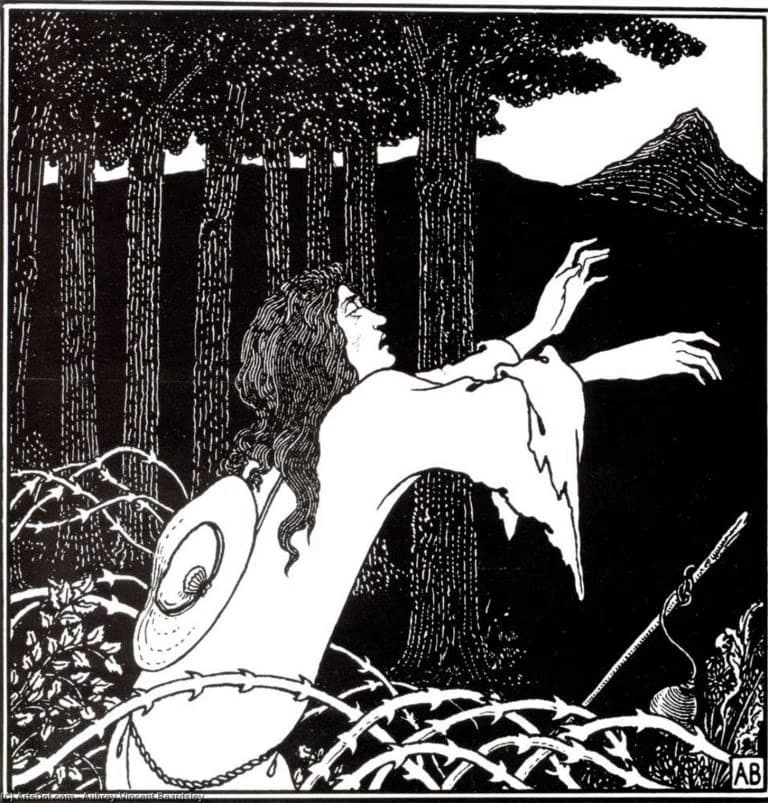

One Wagner work that fascinated Beardsley was Tannhäuser. He has been working on a text version of Tannhäuser called Venus and Tannhäuser and made some drawings for it, but, in the end, his version of the ‘sex, sin, and forgiveness’ story became too pornographic, and it was only published in an unfinished and expurgated version.

Beardsley: Frontispiece for Venus and Tannhäuser, 1895

Beardsley: The Return of Tannhäuser to the Venusberg, 1895

Richard Wagner: Tannhäuser – Act I Scene 2: Geliebter, sag, wo weilt dein Sinn? (Michelle Breedt, Venus; Torsten Kerl, Tannhäuser; Bayreuth Festival Orchestra; Axel Kober, cond.)

Again, in these two illustrations, we see the mix of Burne-Jones–influenced detailed calligraphic style and Beardsley’s black style, just as we saw in the Siegfried picture above and the Wotan/Loge pictures.

Beardsley had a complicated love/hate relationship with Wagner. His illustrations show the most perfect understanding of Wagner’s vision but also veer into the dark side of that vision. He could be reverent and mocking all in the same work. The increasing pornographic nature of his illustrations meant that large circulation of his art was not possible. In the 1907 edition (for private circulation) of Venus and Tannhäuser, the Foreword says: ‘Only a portion of this work, Beardsley’s most ambitious literary effort, has hitherto been printed, with the title “Under the Hill”. The present work is a complete transcript of the whole of the manuscript as originally projected by Beardsley. It has been deemed advisable, owing to the freedom of several passages, to issue only a limited number of copies for the use of those literary students who are also admirers of Beardsley’s wayward genius’.

Beardsley’s art responded to the enthusiasm of the Wagnerites around him, was informed by his own love of Wagner’s music, and helped give it greater artistic depth and dimension than it had had before him.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter