“They will outlive all changes of fashion in music”

The collection of six sonatas in trio sonata form for organ BWV 525-530 by Johann Sebastian Bach are generally regarded as masterpieces for the instrument. We find them in a manuscript dating from between 1727 and 1730, that is, from around Bach’s first years in Leipzig. Bach supposedly fashioned the collection for his eldest son Willhelm Friedemann, “who by practising them, prepared himself to be the great organist he later became.” Since Bach was the defining organ virtuoso of his time, they are also ranked amongst his most difficult compositions for the instrument.

Organ Wizard

Johann Sebastian Bach playing the organ, c. 1881

These sonatas require the right and left hand to play independent melodic lines on separate keyboards while the feet play the basso continuo. A noted organist wrote, “the organ sonatas are disarmingly attractive and immediately appealing to the listener, though they pose ferocious interpretive and technical demands for the player.” It’s a real challenge of coordination, playing three lines of music on two keyboards and pedal with all four limbs.

Renowned organist Peter Williams writes, “The two hands are not merely imitative but so planned as to give a curious satisfaction to the player, with phrases answering each other and syncopations dancing from hand to hand, palpable in a way not quite known even to two violinists. Melodies are bright or subdued, long or short, jolly or plaintive, instantly recognizable for what they are, and so made (as the ear soon senses) to be invertible. Probably the technical demands on the player also contribute to their unique aura.”

But technical bits aside, here is what the Bach biographer Nikolaus Forkel had to say. “One cannot say enough of their beauty. They were composed when the author was in his most mature period and may be considered as his chief work of that description.” Individual sonatas and movements have various histories, some composed specifically for the collection, while others are transcriptions or adaptations from earlier works.

J.S. Bach: Trio Sonata No. 1 in E-flat Major, BWV 525

Outlive all Fashion

A contemporary reviewer writes, “There still exist six trios by Bach for the organ, for 2 manuals and pedal, that are so beautiful, so new and rich in invention, that they will never age but will outlive all changes of fashion in music.” And a different critic in 1799 asserts that “pieces of this kind, when properly executed, exceed everything else in the art of organ-playing.” From such high praise, it becomes clear that the Organ sonatas have no real connection to the functional repertory of a church organist but are primarily concerned with mastering the technical aspects of the instrument.

Every organ is capable of a huge variety of sounds, unique to each particular instrument. These changes of sound colour are accomplished by selecting various “stops” on either side of the keyboard. Each stop will activate a specific set of pipes and produce a process known as registration. As you might well imagine, registrations for Bach’s Trio Sonatas are highly personal and, on occasion, hotly debated. Some organists prefer three musical lines in different tone colours to hear the counterpoint more clearly, but others suggest that the “sonatas benefit from a similarity of timbre in the voices.”

Arrangements and Transcriptions

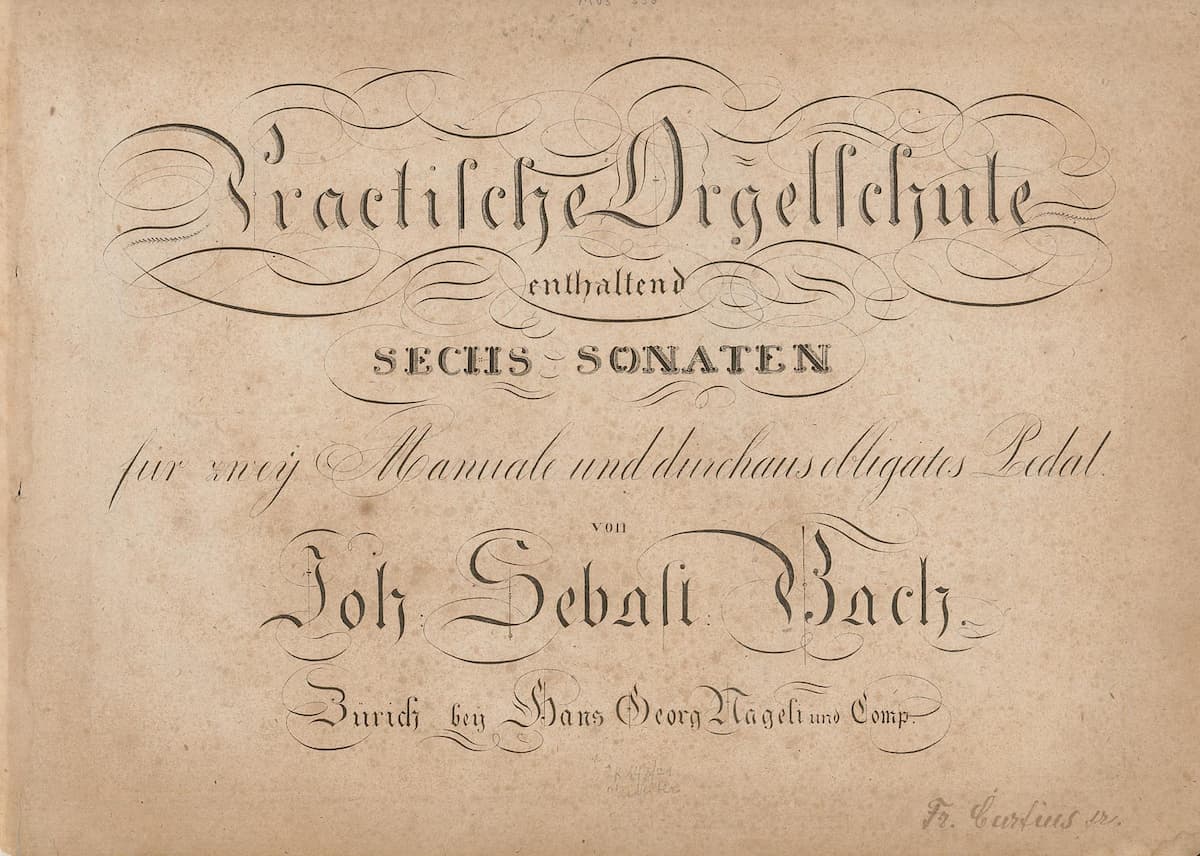

Bach’s Organ Sonata No.1 in E-flat major, BWV 525 title page

As we know from Bach, and in fact from the entire Baroque era, it was not uncommon for composers to rework their own or another composer’s musical material. I won’t give you a play of how Bach arranged and transcribed various movements of his organ sonatas, but let’s keep in mind that later eighteenth-century arrangements of the Six Sonatas were not uncommon. Mozart arranged BWV 526 for string trio, and an unknown arranger transferred the music to two harpsichords. There is also an arrangement for three hands on one piano, and in more recent times, we find a myriad of beautifully crafted arrangements for various Baroque ensembles.

J.S. Bach: Trio Sonata No. 5 in C Major, BWV 529 (Palladian Ensemble)

Style and Taste

With the advent of historically informed performance practice, performers and scholars devote their time to lengthy discussions of appropriate style and good taste. Yet, the universal genius of Bach’s music is so versatile that it can easily suffer the transfer into different kinds of mediums. At least, that’s my personal opinion. What is interesting about the Organ Sonatas, however, is the fact that there are no direct models that have so far been discovered. The various elements of form and texture were familiar to Bach by the time he reached Köthen. Organ chorales in three parts, dividing the texture into two manual parts above a bass-like pedal were common, and Bach had long known three-part textures with cantus firmus.

The three-part texture of the trio sonata in ensemble music was also familiar throughout Europe, but the three-movement design for each sonata appears to originate in the concerto repertoire. As such, the closest parallels to the Six Sonatas are probably found in works for solo instruments, like the violin, flute, or gamba, and cembalo obbligato. As you can hear, the two upper parts of the Six Sonatas are always in dialogue, with the pedal resembling a continuo line. The first movements of the Six Sonatas are more concert-like in form, while the final movements could generally be assigned to solo sonatas.

A Designed Collection

While many of these features are found in various types of instrumental trio sonatas, “the variety and comprehensive coverage of these features within the 18 organ-trio-sonata movements appears to be deliberately planned.” As a scholar writes, “Not for the only time in the music of J.S. Bach, a set of pieces is planned as if to show the scope open to a composer working in a particular, restricted medium.” We only need to think of the Well-Tempered-Clavier, the Partitas for various solo instruments, and the majestic Art of the Fugue.

J.S. Bach: Trio Sonata No. 4 in E minor, BWV 528 (King’s Consort; Robert King, cond.)

Criticism from Johan Adolph Scheibe

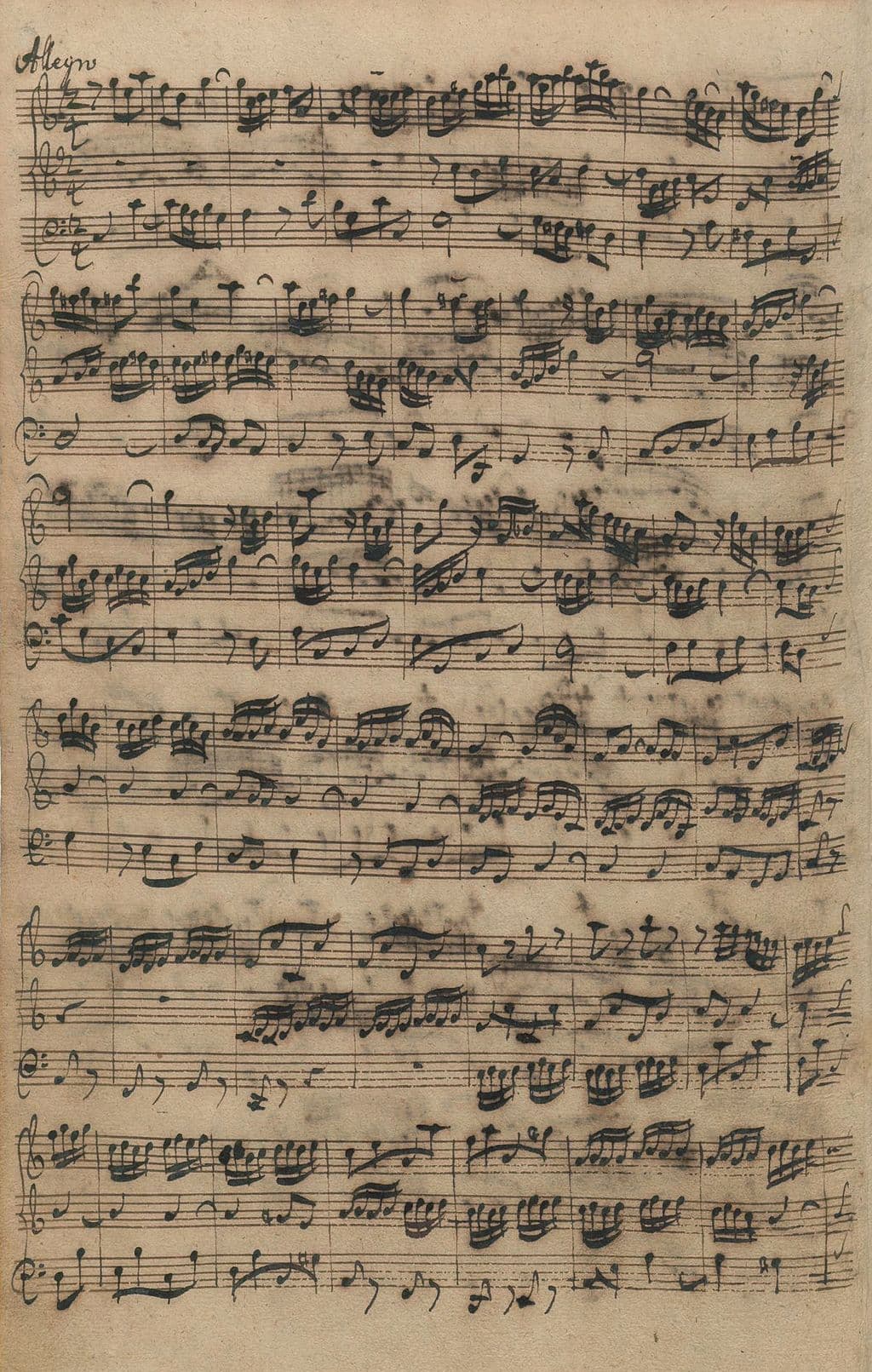

Bach’s Organ Sonata No.5 in C major, BWV 529 – III. Allegro autograph score

Bach’s former student, the music theoretician and organist Johan Adolph Scheibe was highly critical of his teacher’s composition. According to Scheibe, “Bach’s music was artificial and confusing in style, and the notation of such elaborate ornaments, rather than leaving ornamentation to the performer, obscured the melody and harmony. Rather than a clear division between melody and accompaniment, Bach made all voices equal in his brand of polyphony, which made the music overloaded, unnatural, and oppressed.” In short, Bach “deprived his pieces of all that is natural by giving them a bombastic and confused character, and eclipsed their beauty by too much art.”

Sonatas in Concerto Style

Perhaps surprisingly, Scheibe only praised the trio sonatas, and he devoted a lengthy section of his treatise to them. Scheibe looked at Bach’s organ sonatas in terms of genre and at the role and style of the bass part, and the three-movement layout. He writes, “…The ordering that one usually observes in these sonatas is the following. First, a slow movement appears, then a fast or lively one; this is followed by a slow movement, and finally, a fast and cheerful movement concludes. But now and then, one may omit the first slow movement and begin immediately with the lively one. One does this particularly if composing sonatas in concerto style…” Having made the distinction between a proper or genuine sonata and the sonatas in concerto style, Scheibe concludes that Bach’s organ sonatas are “his main contribution to the genre of sonatas in concerto style.

Given the limitations of the organ pedalboard, it naturally follows that the bass line has to be simpler than the two upper parts in the manuals. When the theme passes to the pedal, it is usually simplified and stripped of ornaments. Omitting a first slow movement, although we find some slow introductions, was probably a very conscious decision of Bach. Earlier sonatas for violins and harpsichords are mostly composed in four movements, with the opening slow movement carrying a drawn-out melody for the solo instrument. As a scholar writes, “this style of writing would clearly not have translated well to the organ.” Instead, the harmonies are provided by the pedal and the two manual parts, play single melodic lines throughout.”

J.S. Bach: Trio Sonata No. 3 in D minor, BWV 527

Short musical Guide

Countless books and dissertations have been written on the motific, contrapuntal and aesthetic beauty of the Bach Sonatas. Sometimes, all that verbiage gets in the way of actually enjoying the music. So, instead of giving you a blow-by-blow description, here comes a brief musical tour of each sonata. The opening ritornello motif of BWV 525 builds a rising E-flat Major triad. You can hear that triad throughout, including when the pedals take it up towards the end of the movement. The slow movement follows a two-part song form, and all voices take turns presenting a lyrical opening theme. The closing movement of BWV 525 is the only outer movement in the entire group not constructed as a ritornello, but this fantastic two-part song form vigorously involves the pedals in the motific development.

Sonatas 2-4

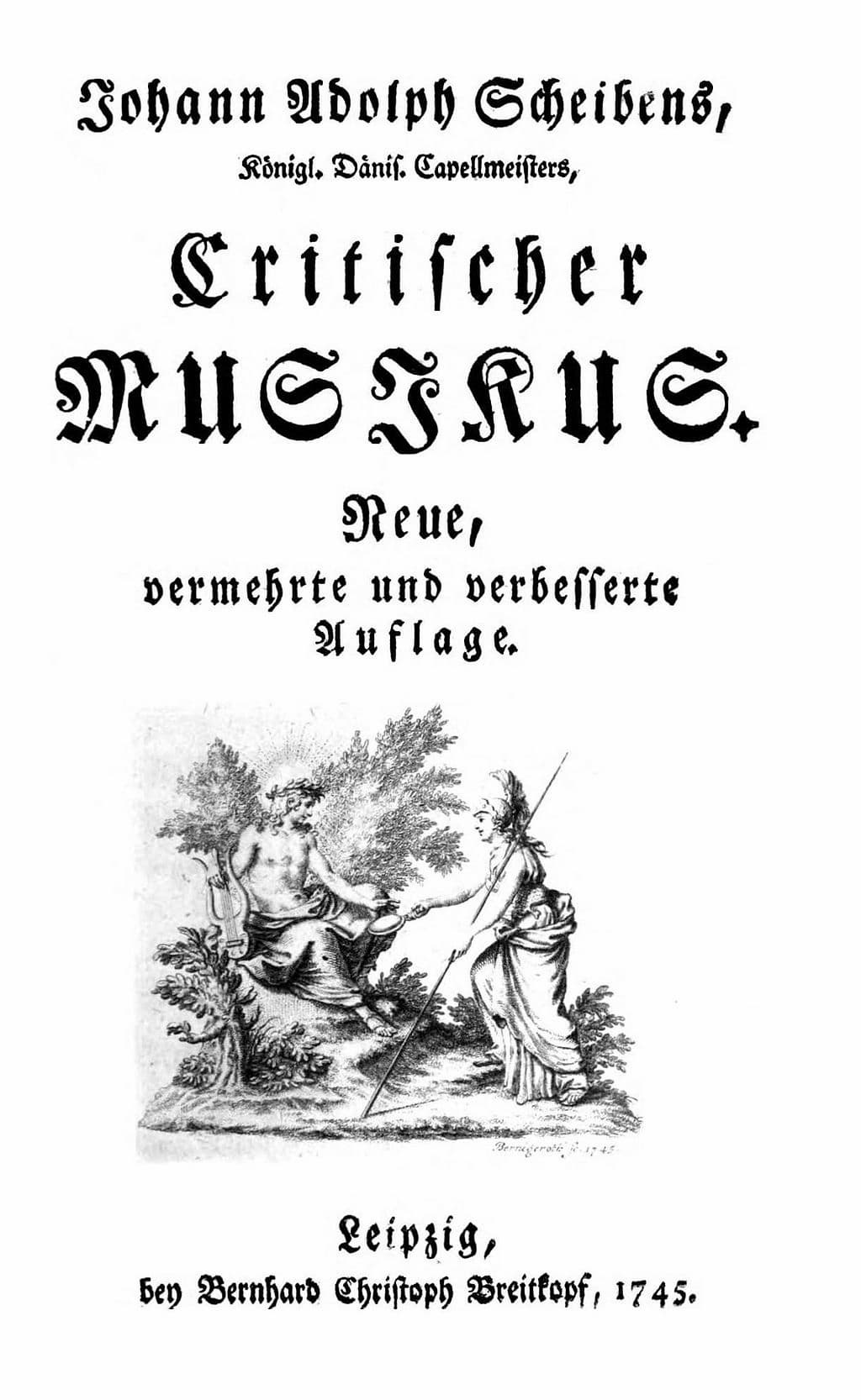

Johan Adolph Scheibe

One of the most technically demanding works in this collection of sonatas is BWV 526 in C minor. It opens with a homophonic ritornello, and the theme is guided by thirds in the upper voices connected by spectacular leaps. The second movement develops a free structure from a triad motif, followed by a descending sigh. The pedal gets a real workout in the concluding movement as it is deeply involved in fugal processes throughout. Sonata No. 3 in D minor, BWV 527, opens with an Andante movement, the only one in the entire collection.

The second movement is reminiscent of the shepherds’ music in the Christmas Oratorio, and the concluding movement follows a delightful da capo structure.

The E-minor sonata, BWV 528, is a compilation of three movements that already existed. The first movement is almost identical to the Sinfonia from the Cantata BWV 76, and a short “Adagio” introduction swiftly moves to a “Vivace,” all sounding like a French Overture. The second movement is also in the minor key, and the beautiful imitation in the upper voices is truly heavenly. The concluding movement has a distinct dance-like character, and there is almost constant triplet motion throughout.

J.S. Bach: Trio Sonata No. 2 in C minor, BWV 526 (Florilegium; Ashley Solomon, cond.)

Sonatas 5-6

BWV 529 in C Major opens with a joyful da capo, and the ritornello theme is once again based on triads. The second movement in A-minor features an expressive theme that provides a stark contrast to the opening movement. It gets properly virtuosic in the concluding movement, as the ritornello theme is picked up and sequenced in the pedals. A delightful second theme is introduced in the episodes, and it all concludes with a dizzying array of thematic stretto passages.

The final sonata, BWV 530 in G major, opens with a jolly unison passage between the upper voices. The ritornello returns twice throughout the movement, and the episodes are worked into a circle of fifths. Full of syncopation, grace notes, ornamentations and intense chromaticism, the second movement in E minor follows two-part song form. The concluding movement returns to the upbeat feeling from the opening movement. The ritornello makes ample use of the pedal, and a delightful second theme is introduced in the episodes.

Conclusion

Scheibe’s Der critische Musicus, 1745 title page

You might have noticed by now that I have selected not only the original organ versions but a number of adaptations for different instrumental groupings as well. For me personally, the overall effect of these sonatas is clearly not derived from the manner of execution, but from the incredible raw material fashioned by Bach. These sonatas are not esoteric or abstract explorations of counterpoint, but an expression of stylistic features available to Bach during his time. And of course, there has never been any greater composer combining craftsmanship and emotion. But that’s not all; if you ever get good enough to play these sonatas on the organ, it is truly one of the most thrilling and satisfying activities you can legally engage in as a musician.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter