Henry Vieuxtemps

The 19th century saw the emergence of a new kind of democratic society, and musical life began to center on the public concert hall. Whereas previously the musician had functioned under a system of aristocratic patronage, they now were supported by a new middle-class audience. Solo performers began to dominate the concert halls, and they became superstars idolized by the public. Under the spell of Niccolo Paganini, the most celebrated violin virtuoso of his time, Henry Vieuxtemps (1820-1881) made his mark as a performer early on. Hector Berlioz wrote, “Mister Vieuxtemps is a prodigious violinist in the strictest sense of the word. He does things I have never heard done by any other before. He posits frightening dangers to the listener, but he stays calm and unshaken, confident that he will succeed.” And Victor Hugo, a great admirer, greeted Vieuxtemps with the words, “I took such pleasure in applauding today what everyone will admire tomorrow.” And even Paganini was heard saying, “This little boy will become a great man.”

Henry Vieuxtemps: Hommage a Paganini, Op. 9 (Ruggiero Ricci, violin; Marco Vincenzi, piano)

Niccolo Paganini

It was Franz Liszt’s fundamental insight that virtuosity, instead of remaining a purely peripheral part of music, was capable of participating in the romantic revolution. Virtuosity came to be part of the history of music as art. This highest standard of musical technique and performance only becomes meaningful, however, when it is shared with an audience. And thus the traveling virtuoso came into existence; that particular brand of musical adventure, as we well know, is still going strong today. In the winter of 1843-1844 Henry Vieuxtemps made his first tour of the United States. During the first three months of 1844, he visited the city of New Orleans, where he received great critical acclaim. Stimulated by the Creole atmosphere Vieuxtemps apparently composed a violin piece based on a black dance he heard during his stay. “This short work, only recently discovered, is the earliest known classical setting of Creole music. Clearly, traveling virtuosos tailored their repertoire to the national communities they visited, and Souvenir d’Amerique represents a greeting from the Old World to the New.

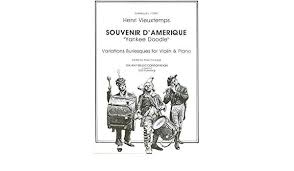

Souvenir d’Amerique

During his second American tour in 1857/58, Vieuxtemps performed 75 times in less than three month. He later would call this grueling schedule a “crime against music.” His wife Josephine Eder, who carefully tapped the existing touring networks, meticulously managed the entire tour. The second American tour was financially highly successful, but besides a grueling schedule Vieuxtemps was also in competition with the violinist Ole Bull. In the American Penny Magazine we read, “I was conversing lately with Meinheer, and I cannot depict to you the astonishment expressed by this illustrious composer when I told him that Ole Bull had been preferred to Vieuxtemps by the Americans. Meinheer regards Vieuxtemps as unquestionably the first violinist of our time for execution, and particularly for composition. I am not sorry to tell this to our Yankee readers, who thought us such fools for expressing the same sentiment on all occasions.” One way of getting the attention of audiences abroad, then and now, was to present works incorporating music of national identity. Although published posthumously, Greetings to America, Op 56, was composed during Vieuxtemps’ American tour of 1843/4. You can’t get much more national then to provided bravura variations on “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and “Yankee Doodle.”

Henry Vieuxtemps: Greetings to America, Op. 56 (Gerard Poulet, violin; Liège Philharmonic Orchestra; Pierre Bartholomee, cond.)

Souvenir d’Amerique – Yankee Doodle vairations

When Vieuxtemps returned from his third tour of the United States in 1870/71, he understood that the primacy of virtuosity had been undermined by the principle of interpretation. Virtuosity became a criterion of interpretation rather than the other way around. As a performer and composer, Vieuxtemps had always added a more classical dimension to the violin repertoire. Never indulging in sheer virtuosity for its own sake, he now turned to pass on his experience and knowledge to a new generation of violinists. Sadly, his days as a pedagogue were cut short by illness, but he nevertheless occupies a central place in the history of the violin of the Franco-Belgian violin school. His most prominent student Eugène Ysaÿe called his teacher’s works “an endless source of precious teaching. His work has the power to reach the highest artistic joys by guiding the hand of the violinist towards a previously unknown perfection.”

Henry Vieuxtemps: Violin Concerto No. 5, Op. 37 (Jascha Heifetz, violin; New Symphony Orchestra of London; Malcolm Sargent, cond.)