Joseph Haydn was born in the village of Rohrau, Austria, in 1732.

Haydn overcame a difficult childhood to become one of the most influential composers in the history of classical music.

Here are a few biographical tidbits about him:

Haydn in London

- Haydn spent most of his career serving as a court musician at the Eszterháza castle, home of the noble Esterházy family. The lavish estate was about a hundred kilometers from Vienna, which was no small journey by carriage. That distance contributed to his personal and professional isolation.

- Because of his isolation, comparative job security, curiosity, and sense of humor, he enjoyed experimenting with musical genres to challenge himself. He did important work developing and standardizing the string quartet, piano trio, and symphony.

- Haydn became a major influence on the next generation of composers. He mentored Mozart and taught Beethoven.

- In his twenties, Haydn fell in love with a woman who ended up joining a convent, so he married her sister. Not surprisingly, the marriage was desperately unhappy, and both had affairs with other people.

Haydn later explained his unfaithfulness to a biographer: “My wife was unable to bear children, and for this reason, I was less indifferent towards the attractions of other women than I might have otherwise been.”

For her part, apparently, his wife had no interest in his career. Rumor has it she shredded his manuscript paper to use for curling her hair.

Intrigued by what his music sounds like? Here are eleven works by Haydn that trace the development of his career:

Cello Concerto No. 1 (ca. 1761-65)

Prince Paul Anton of the Esterhazy family hired Haydn in 1761. The prince died almost immediately afterward, but, luckily for music history, his younger brother Nikolaus I kept Haydn on.

Nikolaus I was a military man and ran his household with military precision, treating Haydn and the other servants like military officers. The two initially had a rocky relationship but eventually came to work well together.

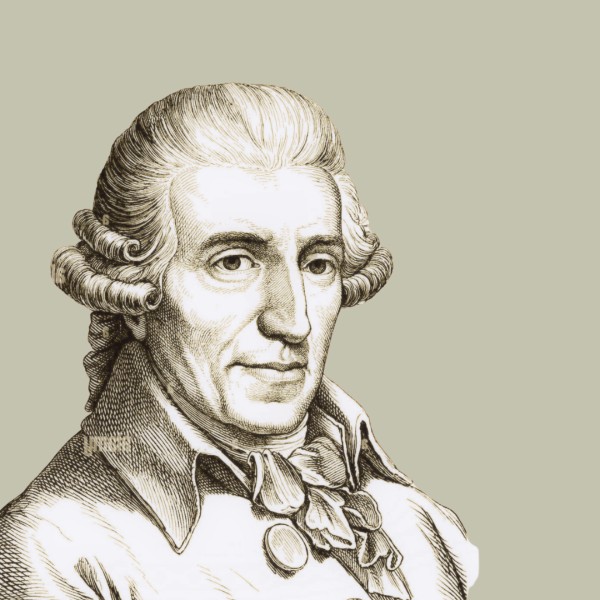

Joseph Franz Weigl © heritage-print.com

Haydn was expected to carry out a large number of tasks, including conducting, composing, staging operas, and performing as a chamber musician with his bosses and his colleagues.

This cello concerto was composed around 1761-65 for his coworker Joseph Franz Weigl, the principal cellist of the court orchestra.

The work is witty and cheerful and is written beautifully for the instrument.

Interestingly, it was presumed lost until 1961, when a score was discovered in Prague. It didn’t take long for it to become a pillar of the classical cello repertoire.

Symphony No. 45 “Farewell” (1772)

In the summer of 1772, the musicians in Haydn’s orchestra were stuck at the castle longer than anticipated. Many of their families lived in Eisenstadt, Austria, about halfway between the castle and Austria, so visiting them was difficult. They were in desperate need of a vacation.

Haydn raised the issue by writing a symphonic finale in which musicians, one by one, depart the stage in a pointed gesture of protest. By the end of the piece, the instrumentation thins out, and the symphony ends with just two violins playing. One of them would be Haydn.

Apparently, the prince got the message loud and clear. The following day, the orchestra was dismissed to go home.

Haydn’s stage directions make this a very early example of music protesting against working conditions decades before the height of the Industrial Revolution encouraged the formation of the labor movement.

Philemon und Baucis (1773)

As we’ve seen, Haydn had many responsibilities as head musician at Eszterháza, including puppet opera.

In 1773, the sovereign of Austria, Maria Theresa, came to visit Eszterháza. That same year, a bespoke marionette theater was constructed in the castle, and Haydn wrote the music for the premiere performance.

The story chosen for the marionette opera traces the myth of Philemon and Baucis, an elderly couple who humbly welcome guests who turn out to be gods. The two humans fall before the gods, apologize for the state of their humble home, and ask to serve them. The symbolism isn’t exactly subtle, but hopefully, Maria Theresa appreciated it.

Piano Sonata No. 38 (1780 or before)

In 1780 Haydn published a set of six piano sonatas, and this is one of them.

It was dedicated to two musically gifted sister pianists, Katharina and Marianna Auenbrugger.

The Vienna-based Auenbrugger family was famous for its musical soirees. When Haydn was able to travel to Vienna, he was always a celebrated guest at their performances.

In addition to being a pianist, Marianna was a composer. (In fact, she studied under Mozart’s rival Salieri.) But she died tragically young of tuberculosis just two years after these sonatas were published.

The sonata is a lovely tribute to two very talented sister artists and a fine example of Haydn’s keyboard/piano sonatas.

The Seven Last Words of Christ (1785-87)

In the mid-1780s, Haydn received an unusual request from a Spanish canon: to compose instrumental music to accompany a Lenten service that would examine Jesus’s seven last words. To pay for this work, the canon sent a cake full of gold coins, which Haydn couldn’t resist accepting.

The first version was written for orchestra and is especially noteworthy for its extremely wide dynamic range, which goes from very soft to very loud.

However, in order to make the music more accessible to more churches and more people, Haydn made an arrangement for string quartet that is often heard even today.

Or…at least we think he did. Interestingly, the transcription isn’t particularly accurate, which has led musicians to wonder if Haydn hired someone else to do it.

Symphony No. 94 “Surprise” (1791)

In 1790, Prince Nikolaus died. It turned out that running a castle the size of Eszterháza with luxuries like marionette theaters had been very expensive. It soon became clear that Nikolaus’s son would have to retrench financially, and that meant shifting resources away from paying for a house orchestra. Haydn, luckily, got a pension. He also—finally—got the opportunity to travel.

In 1791, he headed to London for the first time and proceeded to make a great deal of money there. Audiences adored him, and he wrote a lot of new music for the trip, including this symphony.

In the second movement, Haydn creates a surprising moment when there is an unexpected loud chord at the end of a quiet passage. A legend arose that Haydn wanted to wake up any audience members who had fallen asleep.

However, he later shot down that idea. When a biographer asked if that rumor was true, he said, “No, but I was interested in surprising the public with something new and in making a brilliant debut.” That he most certainly did.

Symphony No. 104 “London” (1795)

This is Haydn’s final symphony, concluding an output of over a hundred. (By comparison, Mozart only wrote 41, and Beethoven only nine.)

Haydn wrote the 104th Symphony for his second trip to London. Even just by itself, it made his trip financially worthwhile. As he wrote in his diary, “The whole company was thoroughly pleased and so was I. I made 4,000 gulden on this evening: such a thing is possible only in England.”

Piano Trio No. 41 (ca 1795)

Haydn dedicated his final piano trio – his forty-first! – to yet another Viennese woman composer/pianist, this one named Magdalena von Kurzböck, who was considered to be one of the best pianists in the city.

The trio has two movements. The first movement is restrained, featuring prominent bass notes in the piano that Haydn became particularly fond of while playing on resonant English instruments.

The second movement is a cheeky joke that asks the violinist to ascend into the stratosphere to make fun of a particular German violinist who has intonation issues.

These high notes give the trio its nickname – Jacob’s Ladder – after the Biblical story where Jacob dreams that he sees a ladder ascending to heaven.

Trumpet Concerto (1796)

In the late eighteenth century, famous Austrian trumpeter Anton Weidinger began playing a seven-keyed trumpet. This allowed for a wider variety of notes to be more reliably played. It was also a stepping stone to the modern valved trumpet, which appeared a couple of decades later.

Anton Weidinger © welltempered.wordpress.com

Haydn took advantage of this technical advancement in this concerto by including notes in the middle and lower registers that were hard to control on other trumpets.

String Quartet No. 63 Sunrise (1796-97)

Haydn made so many contributions to so many genres we haven’t even gotten around to mentioning his incredible output for string quartet!

Over the course of his career, Haydn helped to establish string quartet conventions, including increasing the difficulty of all parts.

Although the first violin has the most obvious role in this quartet – imitating a rising sun – the other instruments have important and interesting parts, too. That’s something that we didn’t see when Haydn began writing string quartets fifty years earlier.

Over the course of his life, Haydn wrote an astonishing total of sixty-eight string quartets.

The Seasons (1801)

In 1798, Haydn wrote an oratorio called “The Creation” that was extremely popular. He followed that up with another oratorio called “The Seasons”, which would be his last major work.

Haydn had a unique request for his “Creation” librettist (i.e., the person writing the script): he wanted the work to be able to be sung in German or English since he was so popular in Britain. It was a tall task, and the English translation wasn’t always totally successful. The music, however, makes up for it.

By this time, Haydn was aging rapidly and composing was not coming as easily as it once did. It took him two years to finish this work. Nevertheless, it remains innovative as ever.

Musicologist Michael Steinberg wrote that “The Seasons” ensures Haydn’s “place with Titian, Michelangelo and Turner, Mann and Goethe, Verdi and Stravinsky, as one of the rare artists to whom old age brings the gift of ever bolder invention.”

Conclusion

In May 1809, Napoleon’s forces invaded Vienna: a difficult experience for anyone, but especially for an elderly man. As troops attacked, he famously joked to others in his household not to worry: “Don’t be afraid, children, where Haydn is, no harm can reach you!”

He was deeply moved when a French soldier came to find him and sang him an excerpt from “The Creation.” It was an indication that his art would outlive the political strife of the Napoleonic era.

Joseph Haydn died peacefully in his home at the end of that month. He was 77 years old.

To learn more about Haydn and his music, check out our Haydn tag.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter