Mattheuspassie manuscript

© Concertgebouw Brugge

Putting together a personal list of all-time favorites is harder than you think. Although it is the product of my personal taste, education, cultural influences and life experiences, human creativity tends to respond to stimuli as diverse as the universe itself. Squeezing it into a simplistic list of top-10—unless we are bean-counting sales over a given period—just doesn’t seem to make much sense. However, being overly concerned about all the masterworks that won’t be on my list is equally paralytic. My personal way of dealing with this conundrum has always been to ask questions. I was a rather difficult child, driving my parents crazy on a daily basis. On my 5th birthday my parents suggested that my name should be changed from “Georg” to “Why?” It was indeed my favorite word growing up—to some extent it still is—because I just wouldn’t be content with simplistic platitudes, regurgitations of herd mentality opinions or worse, sheer ignorance. Which basically means that my top-10 asks some simple, personal, and fundamental questions of the given pieces of music. 1) Does the composer have something meaningful and sincere to contribute to the human condition—transcending the banal, mundane and narcissistic; 2) How is it being communicated and technically executed, and, 3) what is the overall emotional impact? For me, this trinity of questions has always been perfectly answered by Bach’s St. Matthew Passion.

J.S. Bach: St. Matthew Passion

Bigger is not always better, and meaningful musical expression is never tied to a particular style or genre, at least not for me. And that’s why Anton Webern makes it onto my top-10 list. We could be sitting around trying to analyze all the nuts and bolts of this miniature universe for eternity, but we really don’t need to understand all the technical aspects to comprehend the emotional impact. And that, to me, is pure genius.

Anton Webern: Variations Op. 27

Sexual experiences are endless sources of musical creativity. It is a place where romantic notions, cultural will and primitive energies merge. For me Francis Poulenc’s music mirrors this often-conflicted nature of humanity. Unafraid to indulge his urges for promiscuity, nostalgia and for mystic spirituality, one critic famously remarked, “Poulenc’s music may lie in the gutter, but it is always looking at the stars.”

Poulenc: Concerto for 2 Pianos in D Minor, FP 61

Albert Einstein once famously remarked “Mozart’s music is so pure that it seemed to have been ever-present in the universe, waiting to be discovered by the master.” In the end, both Einstein and Mozart were successful in untangling the complexities of the universe and created works of luminous beauty. Mozart was seemingly attuned to the cosmic vibrations of the universe from an early age. He just took a bit of time to figure out what he actually wanted to say. And while it is all too easy to elevate him to god-like status, Mozart reveals himself to be utterly human in his compositions in the minor key.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Requiem

Extraneous events and spiritual encounters did on occasionally influence the music of Johannes Brahms, but in no way did he write into his work the soul felt emotions of his life as an artist. To grasp the subtle shades of meaning in his music, one has to know as much about music, history and the world as Brahms did. And since he attempted to forensically understand everything he encountered, it is an endlessly delightful task. While his music can certainly be enjoyed on a surface level, Brahms’s music demands forensic attention to detail to reveal its full riches. And did I mention that Brahms wasn’t afraid to have an opinion?

Johannes Brahms: Clarinet Quintet, Op. 115

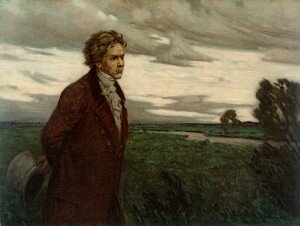

Beethoven on a Walk by Berthold Genzmer

When we talk about composers with definite opinions, Ludwig van Beethoven certainly fits the mould. As a matter of fact, he might well have been the first truly bad boy of music. And we all know about his terrifying hearing affliction. But rather than taking the easy way out—and he did contemplate suicide—he found focus in his art. The most astonishing bit is that there is nothing pessimistic or self-pitying in any of his works. Rather, Beethoven transports us into a world of boundless imagination and optimism, providing a mirror in fact, in which humanity is constantly reflected. The man and his music can be interpreted and approached in endless ways from generation to generation depending on personal interests, agendas, experiences and education. And that, to my mind, is what art and music is all about.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 28, Op. 101

In the year 325, theological experts and ecclesiastical dignitaries met in the city of Nicaea—presently defined as the Turkish city of Iznik—and discussed the exact wording for a profession of faith or creed to be used in Christian liturgy. It took them rather a long time, but in the end they came up with a statement starting with the word “Credo” (I believe). A second council held at Constantinople in 381 approved several modifications to the original statement, and the “Nicene Creed” became the only authoritative statement of Christian faith, accepted by the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Anglican, and major Protestant denominations. Palestrina, in this comforting context of spirituality, answers my three questions perfectly.

Palestrina: Missa Aeterna Christi Munera, “Credo”

Madame Butterfly Ellen Kent Production

© whatsonreading.com

I do feel that a Western opera should definitely make my top-10. But how do I go about choosing my personal favorite? From Le nozze di Figaro to Otello, from Meistersinger to Wozzeck, and from L’Orfeo to Carmen to Norma and Rosenkavalier, the world of opera is full of exceptional choices. As such, I have gone with a gut feeling—not to mention emotionally appeal—and decided on Puccini’s Madame Butterfly. Not unlike Turandot, this fantastic opera is still much maligned for its lack of cultural authenticity. Not sure about that, as it fits perfectly within the musical and cultural context of late 19th century Europe.

Puccini: Madama Butterfly

For me, Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta is one of the most perfectly proportioned distillations of what music can communicate. Full of contradictions that mirror human existence, it is simultaneously primitive and sophisticated, uninhibitedly wild and tightly controlled, serene and terrifying. It is music that has transcended music without any trace of folk sources, anecdotes or pretty pictures. But it is highly personal, and above all, sincere. It’s a summing up of all that Bartók had accomplished, or hoped to accomplish over the years.

Béla Bartók: Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta

Enough talk, to conclude my top-10 here is the most perfectly conceived work in the entire chamber music literature; at least to me it is!

Franz Schubert: String Quintet in C Major, D. 956