Ever since the seventeenth century, composers in every generation have explored the Orient for musical and dramatic inspiration. In fact, the sheer durability of this Orientalist obsession in music has greatly extended the language of music by employing eastern instruments, tunes or perceived melodic, harmonic and rhythmic conventions. Orientalist passion of the 18th Century centered, for obvious reasons, on court intrigue, military prowess and seraglio stories of the Ottoman Empire. In due course, and gradually differentiating between Oriental ‘Others,’ composers looked at history and fable for programmatic ideas, operas and ballets. “Orientalism, whether in subject matter, melodic and rhythmic invention or ethnomusicological borrowings became a highly significant stream in European cultural fabric, and increasingly, in the United States as well.” Yet significantly, very few composers working in the 19th-and early 20th centuries actually traveled outside their respective Western homelands. As a result, musical characterizations, alongside other artistic expressions of the East frequently contain rather uncomfortable blends of naiveté and exotica.

Ever since the seventeenth century, composers in every generation have explored the Orient for musical and dramatic inspiration. In fact, the sheer durability of this Orientalist obsession in music has greatly extended the language of music by employing eastern instruments, tunes or perceived melodic, harmonic and rhythmic conventions. Orientalist passion of the 18th Century centered, for obvious reasons, on court intrigue, military prowess and seraglio stories of the Ottoman Empire. In due course, and gradually differentiating between Oriental ‘Others,’ composers looked at history and fable for programmatic ideas, operas and ballets. “Orientalism, whether in subject matter, melodic and rhythmic invention or ethnomusicological borrowings became a highly significant stream in European cultural fabric, and increasingly, in the United States as well.” Yet significantly, very few composers working in the 19th-and early 20th centuries actually traveled outside their respective Western homelands. As a result, musical characterizations, alongside other artistic expressions of the East frequently contain rather uncomfortable blends of naiveté and exotica.

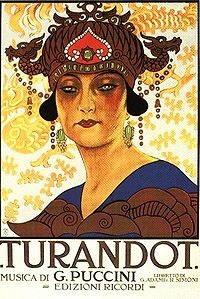

When applied to an imaginary China, this phenomenon — termed Chinoiserie in European artistic styles since the seventeenth century — reveals hidden beliefs, prejudices, aspirations and idealized visions of the Land of the Red Dragon. Cultural critics have suggested that it was Western imperialism that actually shaped our ideas of Asia, “Orientalism is a Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient.” And recent musical research suggests, that, “a stereotype of the Chinese, particularly evident in lighter popular music genres, came to be a dialect that referred to a widely understood musical designation. A body of musical gestures evolved that were able to transcend their musical context and genre to become signifiers of a given culture.” If the lighter popular music genres, including musicals and operettas, were blatant and overt carriers of these cultural signifiers, we would certainly expect a significantly higher level of sophistication to govern Oriental representation in opera. And such is the case in Giacomo Puccini’s unfinished opera Turandot, which strives for authenticity within the context of imagined theatricality. Puccini had long dabbled in the exotic, not only with Madama Butterfly (1904) but also with the Californian gold rush in Fanciulla del West (1910). In 1920, Puccini was once again searching for a suitable opera topic. Rejecting Oliver Twist and various Shakespearean plays, Carlo Gozzi’s “Fiabe Cinese teatrale tragicomic,” Turandot of 1762 was deemed a suitable choice. This play in 5 acts details the story of a cruel Chinese princess whose suitors must answer three riddles or be put to death, and of the prince who falls in love with her. Translated into German prose by August Clemens Werthes in 1779, it was rewritten by Friedrich Schiller in verse for a performance in Weimar in 1802.

Giacomo Puccini