You may not be able to name the title but you must have heard the famous soprano aria “Un bel dì vedremo” from Giacomo Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly or Madama Butterfly. In this article, let us revisit the inspirations and plots of Puccini’s opera while discovering who is the best Madame Butterfly.

Maria Callas Sings Puccini’s Madame Butterfly

The Best Madame Butterfly

Being one of the most widely performed operas, one can find various performances of the aria “Un bel dì vedremo”, sung by Cio-Cio San (Butterfly) as she imagines the return of her absent love, Pinkerton. Renata Tebaldi and Maria Callas both delivered the most sublime singings with a different character; while Angela Gheorghiu and Anna Netrebko showed the emotional depth of Cio-Cio San. And how about a bitter-sweet version by Maria Natale? Let us know which opera singer is your best Madame Butterfly!

Historical Context of Madame Butterfly

Puccini’s Madame Butterfly poster

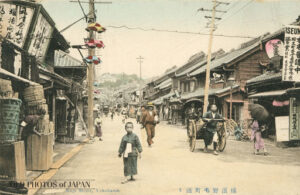

Now let us understand the inspiration and historical background of Madame Butterfly: During the early part of the 17th century, Japan entered a period of self-imposed isolation. Mindful of the rapid spread of Christianity among its peasants and suspecting foreign traders of preparing for a military invasion by Western powers, the Shogunate placed foreigners under increasingly tighter restrictions. Eventually, it completely expelled traders, missionaries and foreigners with the exception of Dutch and Chinese merchants who were restricted to a man-made island in Nagasaki Bay and small trading posts outside the country. In essence, this attempt to keep the world at bay — which was not as successful as everybody claimed–lasted for more than 200 years. Eventually, the American naval Commander Matthew Perry brought his fleet and heavy cannons to Yokohama Bay in 1853 and gently — by firing a 21-cannon salute during a Christian burial — convinced the Japanese to open their ports to foreign trade. Perry returned with an even larger fleet and bigger cannons in 1854, and he subtly suggested that the Japanese might establish formal diplomatic relations with the United States. In 1858, the first U.S. consul to Japan, Townsend Harris, secured commercial and diplomatic privileges that also exempted U.S. citizens living in certain ports from the jurisdiction of Japanese law.

Renata Tebaldi Sings “Un bel di vedremo”

Giacomo Puccini © murashev.com

Perry’s tactful negotiations and the implementation of the Harris treaty not only brought economic benefits to both sides, but also accorded fringe benefits to American man living in Japan. One of these little pleasures of life was the ability to “rent a wife”. For a small monthly fee, a healthy lad could procure a “docile, doll-like Japanese wife, and live in a miniature house surrounded by exotic gardens and flowers.” These marriage contracts — and they were vigorously advertised in glowing and seductive terms — were not legally binding, and could be abandoned at any time. As has been pointed out, the Japanese wives had no legal rights to alimony, property, inheritances or children. It is hardly surprising that these exotic conventions quickly fueled the Western European imagination.

Yokohama in the early 1900’s

© oldphotosjapan.com

At the forefront of popular culture was the fictional account of the French naval officer Pierre Loti, who published his faux memoir Madame Chysanthème in 1887. Loti was not entirely sympathetic to the plight of his Japanese geisha; rather, he portrayed her as a calculated money grabber who simply waited for her next “husband”. In response, Felix Regamey penned his own novel, Le cahier rose de Mme Chrysansthème in 1894. Told from the perspective of the geisha, he takes a much kinder view. And in 1898, the American lawyer John Luther Long published a romanticized trope in Century Magazine. Of course, the musical community had not been idle, and Camille Saint-Saëns published his opera La princess Jaune, in 1872. Gilbert and Sullivan satirized British infatuation with all things Japanese in the 1885 production of Mikado, André Messager’s brought Madame Chysanthème to the operatic stage in 1893, and Pietro Mascagni dealt with the subject matter in his opera Iris of 1898.

Angela Gheorghiu Sings “Un bel di vedremo” from Puccini’s Madame Butterfly

The Music of Madame Butterfly

Geisha image circa 1910 © rubylane.com

However, the most important textual source for Giacomo Puccini’s treatment of the subject appears to have been the one-act Play Madame Butterfly — a companion piece to the farce Naughty Anthony — written and produced by American playwright and producer David Belasco. Puccini saw Belasco’s play in London in 1900, and was particularly touched by Cio-Cio San’s vigil, who stays up all night waiting for Pinkerton’s ship to appear in Nagasaki harbor. Upon his return to Italy, Puccini engaged the services of Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa, who had repeatedly served him in the past. Belasco’s Play eventually became Act II of the Opera, while John Luther Long’s short story was placed in the service of Act I. In terms of music, Puccini was striving for a sense of Japanese authenticity, engaging in exhaustive research to find or at least approximated that sense of musical identity. It has long been assumed that the Japanese melodies in Butterfly originated in a collection of songs published by Y. Nagai and K. Kobatake in 1891 and 1892, or were taken from popular arrangements of Japanese songs, published in 1894 and 1895 by Rudolf Dittrich, respectively. However, recent research indicates that Puccini heard at least two of these Japanese melodies mechanically performed by music boxes.

Anna Netrebko Sings Puccini’s Madame Butterfly

Why Is Madame Butterfly So Popular?

Indeed, no one predicted Madame Butterfly would become one of the best operas nowadays. The two-act version of Puccini’s Madame Butterfly premiered at the La Scala opera house in Milan in 1904. Playing to a hostile audience, who accused the composer of having plagiarized his own score to La Bohème, the performance was an unmitigated disaster. Puccini was undaunted, as he quickly withdrew the opera and returned his fee to the publisher. He began revisions the very next day — cutting material from Act I and dividing Act II into two sections with Pinkerton having a final aria — and three months later, the second version was given in Brescia. In all, Puccini revised his Butterfly for a grand total of five times, with the 1907 version considered to be his final say. In Butterfly, Puccini found a wonderful balance between the sentimental and the overwhelming, as moments of great delicacy alternate with emotional outbursts. The conflict is both personal and cultural, and through his unforgettable melodies — not to mention his sophisticated style of orchestration that cleverly aligns specific instrumental groups and orchestral timbres to match distinct dramatic moments — Puccini’s timeless creation will continue to resonate on a variety of psychological and cognitive levels.

Maria Natale Sings “Un bel dì vedremo” from Madame Butterfly

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter