“Down with impressionism and all those beautiful sonorities”

The young Georges Auric

Georges Auric (1899-1983), born on 15 February 1899 in Lodève, France, was famously included in the group called Les Six by critic Henri Collet in 1920. As a composer, he is probably best known for his ballet and film scores, remaining the only person to have won music prizes at both the Cannes and Venice film festivals. Rejecting the international styles of Russian and German music and shunning the impressionism and symbolism of Debussy, Auric adopted four general compositional strategies.

The scholar and author Colin Roust, writer of the only available monograph dedicated to Auric, has established that in terms of composition, “Auric wanted to participate in groups with other leftist artists; secondly, he wanted to reach a wider audience by writing in more genres; thirdly, he aimed to write music geared towards a younger audience; and fourth, he was looking to express his political views more directly in his music.”

George Auric: Music from Moulin Rouge (1953)

The Prodigy

Auric spent most of his childhood in Montpellier, studying at the local conservatory and receiving piano lessons from Louis Combes, who introduced him to the music of Debussy, Ravel, and Stravinsky. And he discovered the music of Satie in the periodical Musica all on his own. Auric was a child prodigy who began composing before he reached adolescence but subsequently destroyed most of his earliest works.

Auric had phenomenal pianist gifts, and Igor Stravinsky asked him to perform one of the four piano parts at the Paris premiere of Les Noces in 1923. When his parents moved to Paris in 1913, Auric entered the Paris Conservatoire and immediately attracted the attention of Schmitt, Koechlin, and Roussel. He studied with Georges Caussade and met Honegger, Milhaud, and Tailleferre. He was also acquainted with Stravinsky, Apollinaire, Cocteau, Radiguet, Braque and Picasso.

Georgex Auric: 3 Interludes (Sonia de Beaufort, mezzo-soprano; Alain Jacquon, piano)

Writer and Critic

Les Six at the Eiffel Tower in 1921

Auric was essentially a polymath, intelligent, cultured, and intellectually aware. He was always interested in poetry and literature, and at the age of 14, he was introduced to the music critic Léon Vallas. Vallas supported Auric at the time of his admittance to the Paris Conservatory by arranging a performance of the 3 Interludes. He also introduced him to the Société Nationale de Musique and commissioned two articles for his Revue française de musique, one devoted to Erik Satie and the other to César Franck.

This was the beginning of Auric’s writing career, an occupation that helped to solidify his place as part of the Parisian avant-garde. Auric contributed to the Dadaist newspaper Littérature, and he condemned anybody who he considered to be lacking in originally or who was too influenced by romanticism or impressionism. As Colin Roust explains, “During the 1930s, Auric embraced communist ideas and joined some leftist groups, but the apogee of his career as a critic was during the German Occupation, when he edited the clandestine newspaper Musiciens d’aujourd’hui.”

Georges Auric: Adieu, New York! (Peter Toperczer, piano)

The Composer

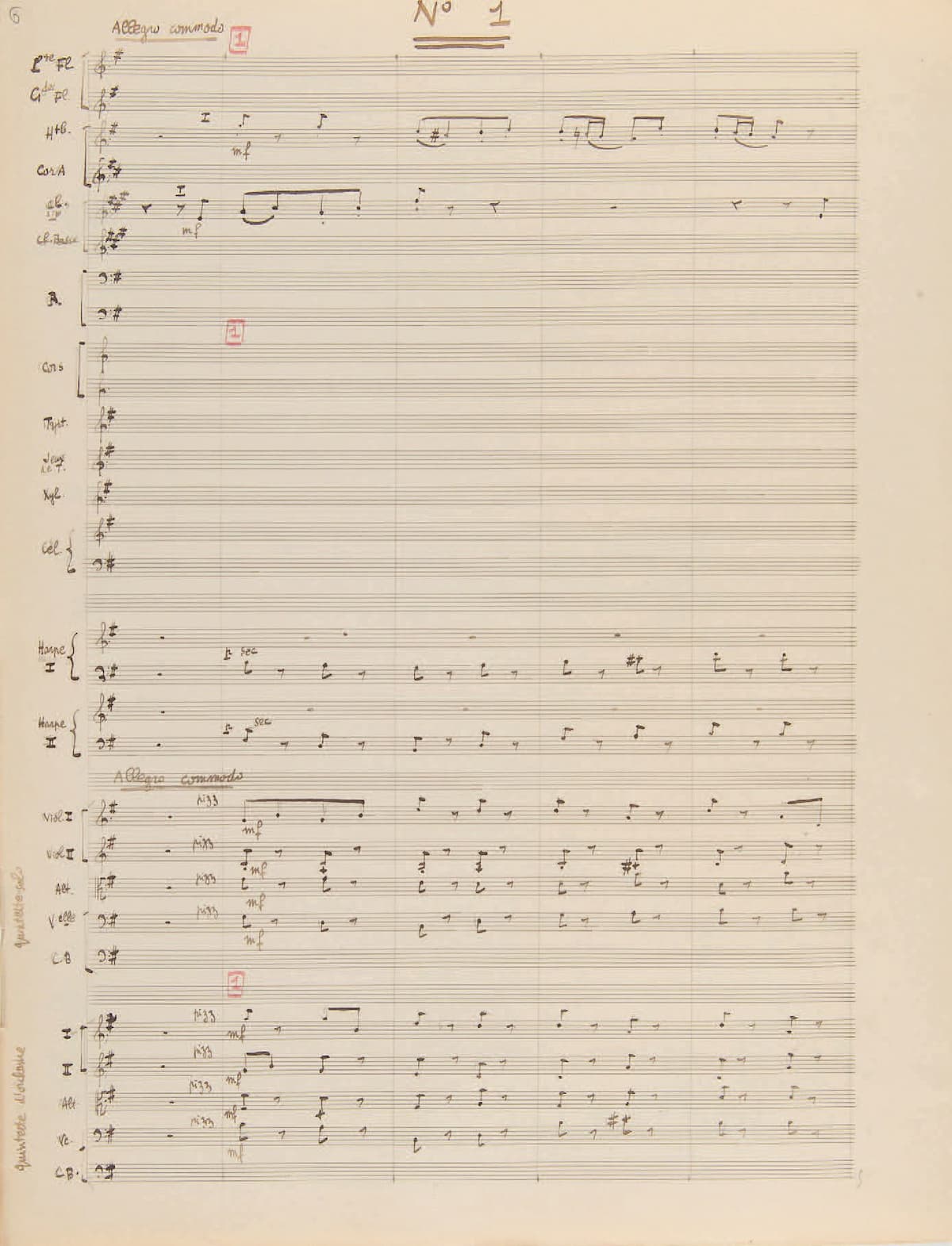

Georges Auric autograph

As Auric explained, “I became a composer, you understand, possibly because of all the literature I discovered at the same time as music. My first compositions were not small piano pieces but short mélodies because when I took home poetry anthologies belonging to my teacher, in the evening, I wanted to set them to music […] I tried to accumulate collections of mélodies, and that is how I think, I decided, in a much more precise way, what my career would be.”

Auric’s exposure and acceptance into Parisian social and artistic life was meteoric. The impact he had on both musical and literary worlds was all the more remarkable because he was mixing with people so much older and more experienced than him, and yet, he made a great impression upon them. “Despite his age, he was a musical and literary force to be reckoned with, and by the time he found himself a member of Les Six, the style of his brilliantly and often acidly aggressive music was well established.”

Georges Auric: Les fâcheux (German Radio Saarbrücken-Kaiserslautern Philharmonic Orchestra; Christoph Poppen, cond.)

Diaghilev

Georges Auric

When Serge Diaghilev heard Auric’s incidental music for Molière’s comédie-ballet Les fâcheux, he asked him to transform it into a ballet. It was first performed in Monte Carlo on 19 January 1924, with the ballet libretto rewritten by his private secretary Boris Kochno. The production did not enjoy success on account that the artists had not sufficiently coordinated their ideas beforehand. In his sketches for scenery and costumes, George Braque meticulously kept to Molière’s text, and Auric composed the music accordingly.

However, Kochno’s libretto and the choreography of Bronislava Mijinska went in different directions entirely, and fierce arguments broke out during rehearsals. In the event, Auric composed music for two more Ballets Russes production, Les Matelots of 1925 and La Pastorale in 1926. In all, Auric composed music for around 15 ballets, but after his acerbic piano sonata of 1931, a work that failed to resonate with Parisian audiences, he decided that film music was to become his primary field of endeavour.

Georges Auric: Piano Sonata

Cocteau

Auric first met Cocteau in June 1915 at the home of Valentine Gross. Their paths crossed once again a couple of weeks later, at a performance of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps at Pierre Monteux’s Casino de Paris production. Auric was thrilled with the location as he shared Cocteau’s fascination with “popular Parisian entertainment venues that included cabarets, music halls, the Cirque Médrano and street fairs.” Auric believed himself and Cocteau to be on the threshold of a personal, artistic, and historically new era.

As he declared, “There is perhaps one thing about [Cocteau] in particular, which will never cease to astonish me. This is the indisputably unrivalled part he has unceasingly and how brilliantly played since he, too, experienced the revelation of all that would one day be almost generally acknowledged as the authentic ‘living’ art of a century… Jean Cocteau possessed the talent, the genius—very special, very rare, and very persuasive—of bringing to light talent, and genius not yet recognized. Our poet would readily become musician, painter, sculptor in turn—as well as dramatist, film director or choreographer…”

Georges Auric: 8 Poemes de Jean Cocteau (Celine Ricci, soprano; Daniel Lockert, piano)

Film

Auric and Cocteau would enjoy a fifty-year friendship and working relationship. In fact, Auric composed the soundtracks for all of Cocteau’s films. As a scholar writes, “their long-term alliance was based on mutual admiration and a shared transdisciplinary artistic aesthetic, motivated at the start by a desire to initiate a post-First World War new French musical identity.” Cocteau’s creative practice included all artistic disciplines except music. He clearly understood, however, that music was an integral part of his productions. As such, “he relied on Georges Auric to fill the musical void in his artistic practice.”

A contemporary journalist watched Auric scoring a movie and she describes the composer as “a big, loosely-built, rather indolent looking man. Auric composes with an absent air, sitting humped over the piano with a cigarette dangling from his lips, under frowning, half-closed eyes, and playing his own melodies apologetically… can he really do this film job, one wonders?”

Cocteau/Auric: Le sang d’un poète (excerpt)

A Certain Unpretentious Charm

During his career, Auric composed well over a hundred French scores, thirty British scores and later music for Italian, German, and American movies. To be sure, La Belle et la bête (1946), Rififi (1954), Lola Montes (1955) and the unforgettable Salaire de la peur (1953), known throughout most of the world as “Wages of Fear,” have remained favourite film classics. By the mid-fifties Auric was scoring a succession of big-budget productions presumably aimed at the American market, but they made little impression.

Auric did develop a lively and sympathetic interest in the avant-garde, and he even flirted with serialism. However, his compositional activities gradually slowed as he increasingly took up administrative roles on the French musical scene. Auric succeeded Honegger as president of SACEM in 1954, and was elected to the “Institut” in 1962, and until 1968, was “a vigorous and galvanizing director of the Paris Opéra and the Opéra-Comique.”

As Auric famously stated in an interview, “I feel very good about my music. My friends and I have had 40 years to get used to short‐sighted articles, and I have never been bothered by them. I feel quite confident that, long after I have disappeared, my music will be remembered while the critics are forgotten. Personally, however, I don’t care whether people play my music after I’m dead. What concerns me is having them play it while I’m living!”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter