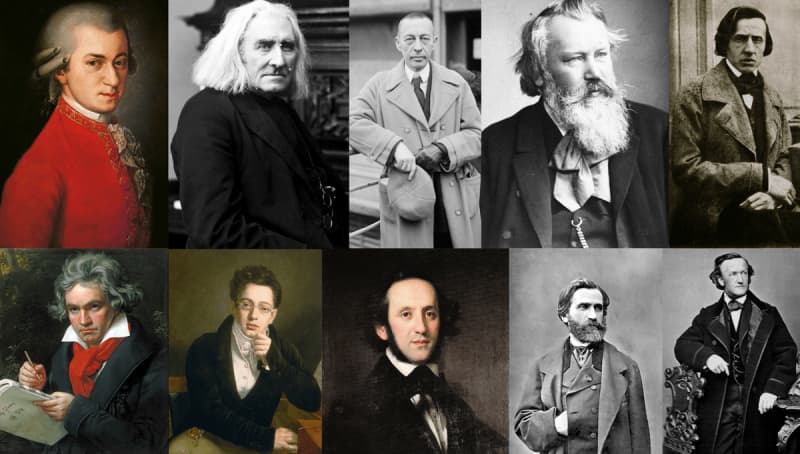

David Cope

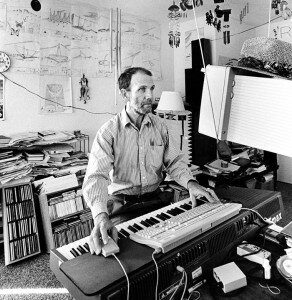

Music created using AI is not new. Back in the 1980s, American composer David Cope experimented with music composed by AI using a computer programme he devised himself. This was actually in response to his own compositional writer’s block and he quickly found that his computer could compose far more – and far more quickly – than he ever could. One afternoon, he left his computer running the composing programme and when he returned, it had created 5000 original chorales in the style of J S Bach.

Cope: Invention No. 1

This music does not happen automatically – though it may appear to. In order for AI to create, it needs to be given a set of instructions, rules and parameters. David Cope fed into his computer a complex code (algorithm) based not only on the patterns and “rules” found in Bach’s music but also the tiny but myriad places where Bach breaks his own rules which makes his music distinctive. Cope also factored in fluctuations in tempo, dynamics, narrative tension and suspense, and indeed as many of the “storytelling” elements in music as he could identify (being a composer himself he would be alert to these details). The resulting music is surprisingly convincing, idiomatically Bach and in many instances indistinguishable from the original. Cope put his AI music to the test with a live performance of music created by Bach, AI and musicologist Dr Steve Larson in the style of Bach. The audience selected the AI piece as genuine Bach and Larson’s piece as composed by the computer. Reactions were mixed. Some people were angry, fearful that the role of composer would become superfluous if a computer could do the job as well – and better, in terms of its ability to create so much music so quickly.

This of course is the true “power” of the computer. Its processing capability is far in excess of anything even the most quick-thinking, mentally agile human being could ever achieve, and it has the ability to run the musical algorithm through seemingly endless permutations. Not only can a computer process many thousands of calculations per second, it can do this 24/7 without ever getting distracted or tired, hungry or bored. Compound this with the ability to network many processors together and their processing power and speed massively exceeds anything we mere humans can manage. The machine learning aspect of the programme enables the system to analyse and identify commonalities which signify the style and characteristics of a particular composer or musical genre, and then compose “new examples of music in the style of the music in its database without replicating any of those pieces exactly” (David Cope).

Other critics of David Cope’s music claimed it had no “humanity”, that it was without emotion or “soul” – unlike music written by human composers whose unique style (apparently) springs from a deep well of emotion and experience. Others denounced it as plagiarism, pure and simple. But this is not “copying” or plagiarism per se because the AI music contains the musical signature of Bach via the algorithm created by Cope and makes new music based on that rather than simply replicating. And don’t all composers “borrow” from others, to a greater or lesser extent?

Cope: Mazurka, Op. 1, No. 2 (after F. Chopin)

Music created by AI presents an interesting philosophical question: where does the “soul” or emotional content of music actually reside? In the notes on the score? In the musicians’ interpretation of those notes? Or in the individual emotional responses of the listener?

The score is just ink on paper, and the organisation of the notes a form of code. We can easily decode this if we know how to read it. One could argue that the notation encodes the “soul” through expression, articulation, dynamics, tempo, harmony and melody – directions which are given to us, the musician, through the score. And as David Cope acknowledged, it is all the subtleties and nuances, the tension and release, suspensions and resolutions which give music its character.

The musicians provide a bridge between the score and the audience and bring the musical code to life. They “interpret” the score, not only by reading and decoding what’s written on the page, but also through their personal experiences. Here we may come close to the soul of the music, and it is that personal interpretation which leads so many people to enjoy music. Consider for a moment how many recordings there are of Schubert’s final piano sonata – yet each is different and each contains the unique ‘fingerprints’ of the individual performer in their understanding and decoding of Schubert’s musical DNA. Equally, the sparsest lead sheet, that pared-down ‘code’ used by jazz musicians for example, can result in a ‘soulful’ or deeply emotional performance.

If there is any ‘soul’ in music, it is perhaps most potently found in the relationship between the music, the performers and the listener, and our personal emotional responses to the music.

The feelings that we get from listening to music are something we produce, it’s not there in the notes. It comes from emotional insight in each of us, the music is just the trigger.

David Cope

What music created by AI and reactions to it reveal is that we can get over-attached to the mystery of human agency necessary for the creation of music, and the varied and finite lives of composers and the romanticisation of their lives and deaths adds to our emotional response to music. We want to believe we can hear in their music Schumann‘s mental breakdown, or Schubert railing against the illness which killed him at 31, and we may attach all sorts of meanings to the music which aren’t actually in the sound itself. We describe the emotions unleashed by the music and speculate on what the composer was trying to say.

AI also poses questions about creativity and given that human beings love making music, and art, and there is already plenty to fill an audience’s lifetime, does its further production need to be automated? David Cope certainly believes it can benefit from automation and regards his AI programme as an extension of his composing self which enables him to compose more quickly. Reassuringly, he also concedes that “real” music is better than the music created by his AI programme, and that professional composers are unlikely to be seriously threatened by automation.

Creativity is simple; consciousness, intelligence, those are hard.

David Cope