© Hoffman Academy

In simple terms, dynamics are directions which indicate how quietly or loudly a piece of music should be played. Dynamics are an important way of conveying mood and enhancing the dramatic narrative of the music.

Directions, indicate in the score, are usually given in Italian and range from simple terms such as piano (soft/quiet) to forte (strong or loud) to more nuanced directions, such as crescendo (gradually getting louder) or diminuendo (gradually getting quieter); both of these terms are either indicated by the words or abbreviations of them (cresc. or dim.) or by “hairpin” signs. Understanding dynamic markings begins at in the first stages of musical study.

Interpreting dynamics is a rather more involved craft, where the composer’s dynamic markings need to be seen in the context of the music. Piano does not simply mean ‘softly’ or ‘quietly’; it can indicate not just a physical sound but also a specific characteristic or mood – intimacy, introspection, sadness. Equally, forte (loud or strong) or fortissimo are not directions to simply hammer the piano: in their solo piano music, for example, both Mozart and Beethoven often use forte or fortissimo directions to suggest a fuller, more orchestral sound. But these dynamics can also suggest particular instruments: in the opening measures of the ‘Hammerklavier’ Sonata, marked fortissimo, Beethoven is suggesting the bright sound of a brass fanfare – trumpets, horns and trombones.

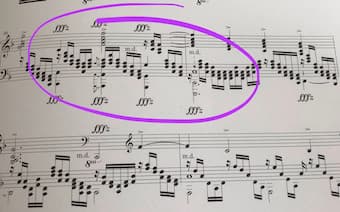

I recently came across a dynamic marking which I’d not previously encountered in music – FFFz (not the musical equivalent of “for f**ck’s sake”!!) which means Fortississimo (very very strong/loud) with added forzando (extra force or emphasis).

This is from a transcription for solo piano of the Adagietto from Mahler’s fifth symphony, and when I shared a screen shot of the bars in question, the Canadian pianist Marc-André Hamelin commented, “I guess it’s just a way to say ‘I mean it!’”. I think this is a very good example of both physical and ‘psychological’ dynamics: on one level, the marking is intended to reflect the sound of the full orchestra, but it is also a direction to imbue this passage with deep, heartfelt emotion.

Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 5 in C-Sharp Minor: IV. Adagietto (arr. A. Tharaud for piano) (Alexandre Tharaud, piano)

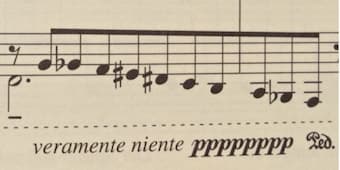

Right at the other end of the dynamic scale is this direction from Ligeti:

which translates as “really nothing”, or perhaps, “barely a whisper”, the direction reinforced by the use of no less than eight p’s.

Schubert often uses a dynamic marking which is physically impossible to achieve on the piano – a crescendo or diminuendo on a single note. This is drawn from string technique, and is, I think, another example of psychological dynamics, whereby Schubert employs this direction to create emotional or dramatic impact. In order to achieve this, the pianist may employ a fractional pause – an “agogic accent” – before playing the note in question. Schubert is a master of dynamics, using them to convey the full gamut of emotions, from a whispered invocation to a scream of terror.

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata No. 20 in A Major, D. 959 – II. Andantino (Llŷr Williams, piano)

Such effects require not only a skilled touch by the pianist, but also a proper understanding of the narrative of the music and the context of the dynamics within that narrative. What is the composer trying to say here? is question we should always ask when we encounter any direction or marking in the score. In addition, calling on the imagination to help bring these directions fully to life will create musical performance which is vibrant, emotional and communicative.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter