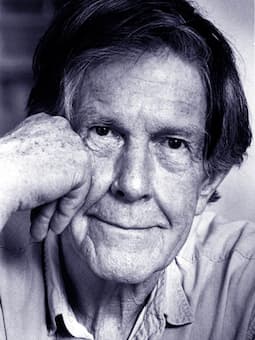

John Cage © encrypted-tbn1.gstatic.com

It seems that the human ear needs time to accommodate and accept the new, the different and the strange. Actually, all senses seem to need some sort of reflection and acceptance from the heart, and the brain. A mid-life adult will remember the child’s aversion to the bitterness of grapefruit, tonic water or beer as younger palates favour the sweetness of treats and cakes; it takes time for the senses to accept the particularity of the taste.

It is quite the same when it comes to art, and particularly music. Some of our most favourite works have endured — and their composers with them — decades, if not centuries, of struggle against the adversity of the public opinion before being accepted and considered for their true value. Long is the list of musical innovators, from Beethoven to Satie, Stravinsky or Cage, who have shocked and disturbed the consensus of what is deemed acceptable in music. This battle is one that no adventurous composer can escape.

So, let’s bring a bit of hope to all creators struggling with artistic and commercial success by remembering how some of — what are today considered as — the masterpieces were received at the time of their creation and premiere.

Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring premiere in 1913

© Keystone-France / Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

Public acceptance can be immediate or in some cases quite a lengthy process, from a decade to centuries; patience is key. We shall not forget that — unfortunately — the laws of politics, finance, culture and trends dictate many of our public opinions.

Bach is today considered as the architect of the Germanic musical tradition, and he is accepted by all as a fantastic composer whose role in shaping music as we know it today has been essential. At the time of his death though, he quickly fell out of fashion, and it was not until Mendelssohn revived his works that the public started having interest in his music again.

Beethoven has had his lot of controversies too; he even had to rewrite the final movement of his thirtieth string quartet. Indeed, the Grosse Fuge had been condemned by the critics and the public — it seemed that their ears were not ready for such innovation and audacity. Today, the double fugue is considered a major inspiration, particularly in the field of film music.

Satie one day declared: “Sir and dear friend – you are not only an arse, but an arse without music”. Directed to the critic Jean Poueigh, who had judged the composer’s Parades mediocre, the work utilised then-radical sound effects which forecasted the whole movement of musique concrète and redefined music in its essence; can noise be music?

Of course, one cannot talk about controversy without mentioning Stravinksy’s Rite of Spring… We now all agree on the revolutionary and rule-setting role of the ballet, however during its premiere in 1913 at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, most minds were brought to boiling levels of in-acceptance resulting in the riots that we all know too well.

Igor Stravinsky: Le sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring) (1967 edition) – Part II: Sacrificial Dance (The Chosen One) (Philharmonia Orchestra; Robert Craft, cond.)

And finally, one cannot write about the difficulties of acceptance for a piece of work without talking about “4’33”. Cage — who wrote the piece at the age of forty — broke all the rules of music in one go — perhaps the most important break since the Second Vienna School. A piece of music with no actual notation, music, written; the music being around us, the surroundings, the environment, our own sounds. Of course, Cage took inspiration in Satie’s concept of furniture music, but brought it to another level. Most people found it to be a joke, while it is well-accepted that today the piece has been responsible for the opening of many doors.

John Cage: 4’33” (Floraleda Sacchi, harp)

One would think that after years of musical innovation, discovery and progress, public acceptance would have gotten better, that the minds would have opened up. But as demonstrated during Mahan Esfahani’s performance of Reich’s Piano Phase in 2016, there is still some progress to be done… During the concert, parts of the audience started booing and clapping the musician shortly after the beginning, and Esfahani was forced to change his repertoire of the night, in order to satisfy the audience…

Steve Reich: Piano Phase (Vincent Corver, piano; Keith Ford, piano)

Many composers live and have lived following the mantra of satisfying their own artistic pleasures and needs from their works — regardless of public approval — yet some still seek some form of acceptance, acknowledgement if not praise from their listeners. Unfortunately, this search is most often unsatisfied during the composer’s life. Unless he agrees to share his soul to the devil, and the public — in other words prioritise modes and opinions over art and innovation — it often takes years, if not decades, before a composer finally finds recognition of his work for the value it deserves…

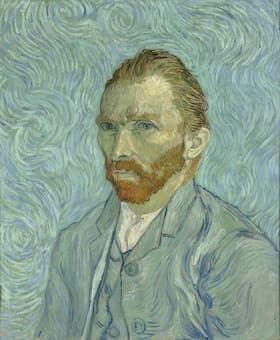

Vincent Van Gogh © Wikipedia

Death brings success… and not only in music. Van Gogh is the epitome of the artist who found recognition after death; with him Gauguin, Monet, Kafka, Bulgakov and not to forget Robert Johnson, Ian Curtis, Tim and Jeff Buckley. There is hope, well somehow.

What is the outcome of this article then? Well, the mantra seems to be: never give up. It is not so much the destination that matters, but the journey; enjoying the creative process and the satisfaction of the achievement is truly the priority. Ultimately, one creates for itself, and for a wider cause than fame, celebrity or simply public recognition. It is all about enriching the human cultural heritage, participating in shaping the artistic world, and providing some with an alternative to daily life.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter