Ravel: Gaspard de la Nuit (Ivo Pogorelich)

I will never forget the first time I heard Croatian concert pianist Ivo Pogorelich live in concert at London’s Royal Festival Hall. The concert, in 2015, had been heavily trailed, hinting that this was Pogorelich’s “comeback concert” after a difficult period in his life, and the anticipation and excitement were palpable before one even entered the concert hall.

The concert itself was a curious affair. A strange psycho-drama played out between performer and page-turner throughout the concert, and some of the playing was distinctly odd: tempos were pulled around and at times it seemed as if the pianist was simply hacking through the music. Much of the performance seemed to unfold like a Shakespearean tragedy – there had been tragedy in the pianist’s own life (his country had been torn apart by war, his beloved wife had died), and this performance seemed freighted with sadness. Yet in the Brahms’ Paganini Variations there was brilliance and beauty, and reminders of why Pogorelich is regarded as a “great pianist”. At the end, many members of the audience were on their feet, roaring their approval, yet the next day the critics eviscerated the performer and his performance, describing it as “crass”, “profoundly unmusical”, “a gruesome, deeply depressing experience”, and “incoherent”, amongst many other brickbats. One newspaper critic suggested that the venue should offer the audience their money back.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 24 in F-Sharp Major, Op. 78 (Ivo Pogorelich, piano)

Ivo Pogorelich © Bernard Martinez, Sony Classical

Pogorelich was dealt another dose of British critics’ opprobrium this year when Sony Classical released his album of two Beethoven piano sonatas and Rachmaninoff’s second piano sonata. This was Pogorelich’s first recording in some 20 years, eagerly awaited by those who had marvelled at his Scarlatti, Liszt and Ravel, and quickly dismissed as “inauthentic”, “self-indulgent”, “incorrect”, and lacking in taste.

Domenico Scarlatti: Keyboard Sonata in D Minor, K.9/L.413/P.65 (Ivo Pogorelich, piano)

He is an eccentric and controversial pianist who follows his own artistic path, and we can either choose to go down that path with him, or not. He has and always will divide opinion with his distinctive interpretations. What I have found interesting in the reactions to his recent performances, and this new recording, is how many commentators, critics, reviewers and listeners suggest that his playing of this music is “wrong”, “inauthentic” or “distasteful”. The adjective “maverick” is used frequently when referring to Pogorelich and in most cases seems to be used pejoratively. The description is wheeled out in relation to other musicians whose playing or manner does not conform with perceived norms of interpretation, performance, stage presentation, and even their musical training; take Glenn Gould, or Lucas Debargue who won fourth prize (and, interestingly, the audience prize) in the 2015 Tchaikovsky competition. His “unorthodox” fingering in scale passages and open-necked shirt quickly earned him the label “maverick”.

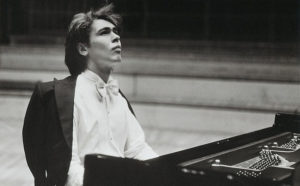

Ivo Pogorelich in1987 © Susesch Bayat

Equally interesting is how critics, commentators and others tend to coalesce around the consensus view of what constitutes “good” or “bad” playing, and here we come up against the notion of “gatekeepers” – those people who set themselves up as protectors of the sacred flame of classical music. Critics and reviewers, concert promoters and agents, record companies and broadcasters, teachers, and knowledgeable listeners all have a role in gatekeeping.

The opinions and demands of these gatekeepers are largely drawn from the customs of interpretation and performance practice which were established towards the end of the nineteenth century, and were quickly subsumed into the culture, teaching and playing of music. These include fidelity to the score and the (largely imagined) composer’s “intentions”, which many gatekeepers regard as inviolable. This dogmatic approach has been further reinforced in the era of recording, and especially now with the wide availability of high-quality recordings, YouTube and other ways of accessing music. Certain recordings are regarded as “benchmarks”, and specialist magazines and broadcasters regularly offer their opinions of what constitutes a “definitive” recording of a work. Performances, live or recorded, which go against the established norm or definitive version of a particular work are dismissed as “wrong”, “inauthentic”, “self-indulgent”, “quirky”, “eccentric”, “maverick”, and a hundred other adjectives which basically mean the critic doesn’t like it. Today, gatekeeping is also a potent marketing tool: gaining the approval of leading critics can go a long way to promoting an artist and give their career a hefty boost.

These gatekeepers demand fidelity and “authenticity” in performance, but seem to forget that notions of “authentic” or “correct” playing and interpretation don’t really apply to music because we simply cannot hear the music of Beethoven or Rachmaninoff as it was heard during the composers’ lifetimes, and without the ability to travel back in time, we can’t ask the composers how their music ‘should’ be performed. Yet the “tyranny of should” persists, perhaps most strongly in the training of young musicians who are taught to uphold tradition and adhere to the established way of doing things (one example is the widely-held view that pianists should never use the pedal when playing the music of J S Bach).

But where is the audience, the non-specialist classical music fan and the general listener in all of this? For the majority of these people, what is set down in the score is of little consequence. People enjoy music because it touches their emotions and takes them out of their everyday lives. Our responses to music are as individual and personal as Ivo Pogorelich’s playing, for the listening experience is always highly subjective. For many at Pogorelich’s 2015 London concert, it was an emotional, thrilling and wonderful performance. Are all those people who stood to show their appreciation wrong? Do those who, like me, have enjoyed Pogorelich’s new recording, lack taste or discernment? By his own admission, Pogorelich sought to “express what was not expressed in that music before” in his new recording, and surely what we seek from music is to be challenged, shaken or overwhelmed, to experience music making which is memorable, rather than be fed the same polite, middle-of-the-road approach every time?

Fundamentally, this is about personal taste, and while the opinions of critics and other gatekeepers may lead us to seek out certain performers and recordings, we should feel free to engage with and explore music on our own terms. And never forget, what is deemed “tasteful” is, simply, a matter of taste!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

How dare those critics criticize one of the greatest!!??

I like his playing and approach but something to note is that being recorded Sony makes you pretty much exactly part of the establishment and not exactly a maverick musician … 😉🙂

Tycker mig ana en utveckling mot en slags puritanism som påminner om den modernistiska arkitekturen i framförandena de senaste decennirna som avlägsnar sig från Rubensteins: “fingrarna skall sjunga”. Inga rubateringar, inga glissandon inget cantabile. Det värsta är väl de kinesiska och japanska pianisterna, som spelar som kulsprutor. Det får inte låta vackert. Skönhet är kitsch.

Not only should pianists not use a pedal when playing Bach, they shouldn’t play Baroque music on a piano – period. That is why we have harpsichords.

@Patricia hahahahahaha

Unbelievable. So wrong! Another gatekeeper to the rescue of the obscure tradition. Bach with pedal and in piano sounds amazing. Piano is a keyboard instrument and his pieces were written for the keyboard. The important thing is to transmite music, not much about the media you use. That is why Bach wrote for keyboard and never specified which keyboard instrument. Bach used whatever instruments he had around, transcribed, etc. Such a obtuse view only hurts this art.

As an amateur pianist who largely explored the use of the pedal, I may nuance your statement. The pedal should not be used to help you play easier. First you must have a clean sound. Exaggerate use of pedal makes a “dirty” sound. The first character of Bach’s music is cleanness. Each sound must be crystal clear, not mixed. It’s about being able to do it or not. That being said, once you get to have that clean sound (very hard to get), your vision might be that certain notes should be kept longer (between bars or so). There you use the pedal, to add color. First of all, your playing should be musical, and if you use the pedal, you should have good reasons to do it.

Even Chopin, when he played, did not like to use the pedal very much. However, many pianists who play his music tend to abuse the pedal; it’s often added by editors even in places where notes are marked “staccato”. I think the pianist must pay respect to the composer’s intention.

Tienes razón@Óscar

Whilst much of Bach’s music is for a keyboard other than a piano, they were invented in his lifetime. His own son had one, on which Bach improvised the theme to what would become the Musical Offering. Pedal is a slightly different matter. They weren’t apparently invented til the mid 1800s.

Given this, and despite the large difference between modern pianos and pianos of Bach’s time, shouldn’t the music be given the chance to live and breathe through a contemporary instrument that allows variation of tone quality and volume through touch?

I can’t imagine either that the next crop of younger musicians would refuse to play existing music on the fortepiano.

Yo apliqué pedal en ciertos compases que me parecieron más bellos así y tuve éxito!

Good article!