In many ways, the career of composer Chou Wen-chung (1923-2019) established a now familiar pattern of intellectuals, artists, and musicians escaping political turmoil in their native China to find opportunities in the United States. A native of Shandong Province, Chou trained as a civil engineer before arriving in the United States on a five-year scholarship in architecture.

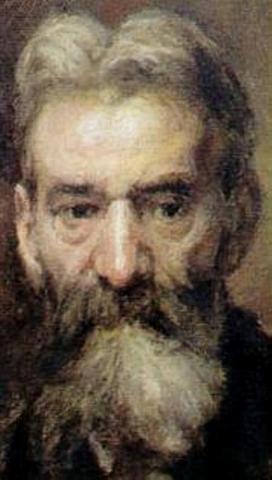

Chou Wen-chung

He quickly changed his mind, however, and enrolled at New England Conservatory to study music with Nicolas Slonimsky, and eventually composition with Edgard Varèse and Otto Luening in New York. As chairman of the Music Division at Columbia University and vice-dean of the School of the Arts, he founded the Fritz Reiner Center for Contemporary Music and the Asian Composers League alongside the Center for US-China Arts Exchange.

Chou Wen-chung: The Willows are New

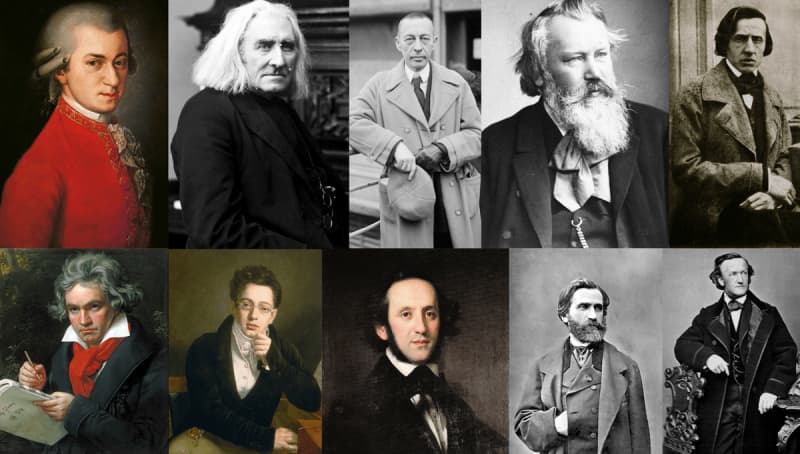

Musical and Cultural Fusion

Primarily remembered as an administrator and educator, Chou the composer never attained the recognition accorded to his students Chen Yi, Bright Sheng, Tan Dun, and Zou Long, who shaped their careers in the commercial, political, and cultural space of convergence located between ethnic authenticity and modernist originality.

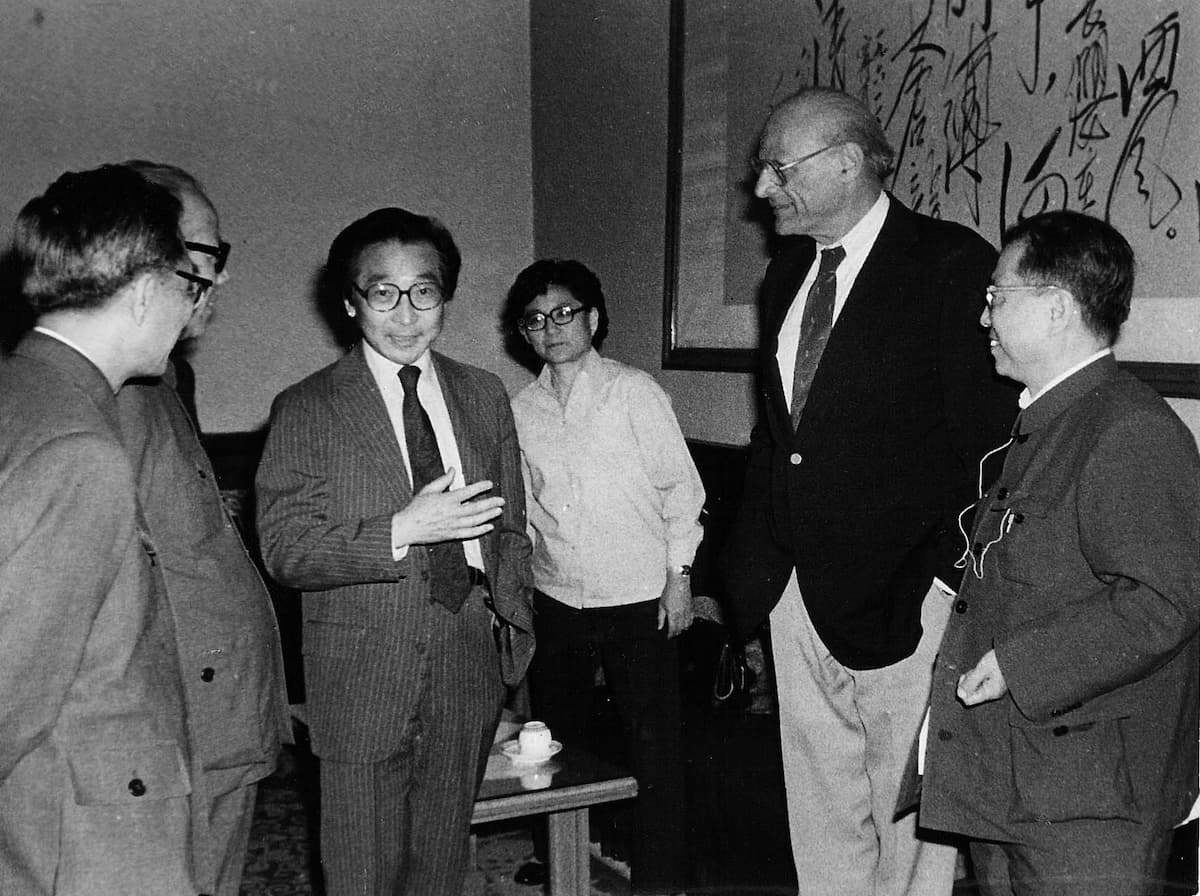

Arthur Miller, Chou Wen-chung and Cao Yu at the Columbia Univeristy, 1980

Chou’s music is not an artificial blend of musical styles and effects but a “successful fusion of Chinese tradition and sophisticated Western vocabulary and style.” The vast majority of his works take as points of departure Chinese poetry, painting, calligraphy, or philosophical and aesthetic ideas. As a commentator writes, “Chou is always conscious of his place in the long tradition of Chinese art.”

Chou Wen-chung: Echoes from the Gorge (New Music Consort; Claire Heldrich, cond.)

Modern Sensibility

During his initial years at New England, Chou mastered a variety of Western compositional techniques, and simultaneously searched for a deeper understanding of his own culture. Not content to collect Chinese folk melodies, Chou devoted himself to the study of the literature, notation, historical background, and playing techniques of traditional Chinese qin music.

As his teacher Nicholas Slonimsky wrote, “a controlled spontaneity and quiet intensity derived from an intimate knowledge of his art and his culture, together with a growth process as organic and inevitable as that of nature, remain requisite stylistic elements. Ultimately, he sought not so much to amalgamate the divergent Eastern and Western traditions as to internalize and transcend contemporary idioms and techniques to create an intimately personal style that reflects a genuine, modern sensibility.”

Chou Wen-chung: Suite for Harp and Wind Quintet

Calligraphy in Sound

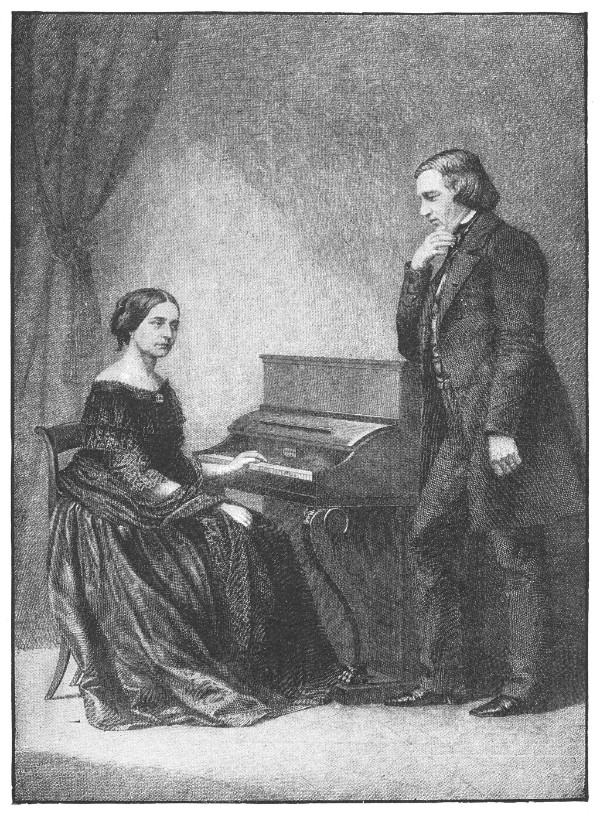

Chou Wen-chung at the piano with Chen Yi

The process wasn’t necessarily an easy one. When he showed his Chinese-flavored fugues to Bohuslav Martinů, the composer stopped after a few measures and uttered a single word, “Why?” Chou quickly understood the incongruity of putting Chinese words into Bach’s mouth. He recognized that the respective musical focus was vastly different. Whereas the West had mastered formal structures, the East focused on controlling subtle inflection of tones.

In accordance with the single-tone concept of Chinese music, Chou started to refine individual pitches and placed them within a clear structure framework. The pitch nuances are not merely decorative but serve as defined structural elements. The art of calligraphy, in its various levels of meaning, constantly serves as the music’s philosophical underpinning.

Chou, Wen-chung: String Quartet No. 2, “Streams” (Brentano String Quartet)

Historical Continuity

Chou Wen-chung © Music Department, Columbia Univerisity

Essentially Chou suggested that “music is calligraphy in sound,” as Chinese calligraphy turns language into a visual medium with the line and shape of characters related to the brushstrokes of Chinese painting. To New York-based critic Ken Smith, “It is not a stretch to hear Chou’s musical gestures, generally minimal drawing from Chinese musical modes, as a sonic equivalent of pen and ink, weighing energy and breath with every stroke.”

Chou would show paintings and calligraphy to his students, “and he would look at brush strokes on the page and see the space between the inner and outer edges of the stroke and the way that it changes as a sort of counterpoint.” For his students, Chou Wen-chung was truly a “wenren,” an artist-scholar during the Qing dynasty. As Chen Yi recounts, “he was a great artist and mentor who combined literature, music, and art all in one.”

In his music and teaching, Chou created a sense of historical continuity by selectively drawing on sophisticated and elitist Confucian artistic aesthetics and philosophies. That banner of historical continuity successfully passed to his students, and it remains the prevailing currency in evaluating intercultural synthesis.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter