I love a good story, and I love it even more if that story is being told in music. And that’s particularly true of instrumental art music with an explicitly narrative content. I suppose that music always conveys or evokes emotions, but I very much enjoy it when a piece has a descriptive title to guide my imagination. So we thought it might be fun to listen to six fun and fanciful symphonies by the Austrian composer Karl Ditters von Dittersdorf (1739-1799).

Karl Ditters von Dittersdorf

Dittersdorf was a highly respected musician and composer who rubbed shoulders with Haydn and Mozart in Vienna. He was a prolific maestro with a high reputation for writing dramatic works, especially the “Singspiel,” and he wrote much instrumental music, including roughly 120 symphonies, a series of concertos, and chamber music.

Dittersdorf set to work in 1783 to compose 12 programmatic symphonies depicting stories in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. That particular compendium of Greek and Roman mythology and legend was written by the Roman poet Ovid around the year 8 before Christ. It spans 15 books, is cast as a Latin narrative poem, and has been called “one of the influential works in Western culture.” To make it easier for his listeners, Dittersdorf introduced each movement with a direct quotation from Ovid’s text.

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 1 in C Major, “The 4 Ages of the World” (Larghetto) (Cantilena; Adrian Shepherd, cond.)

18th century French engraved protrait of Ovid

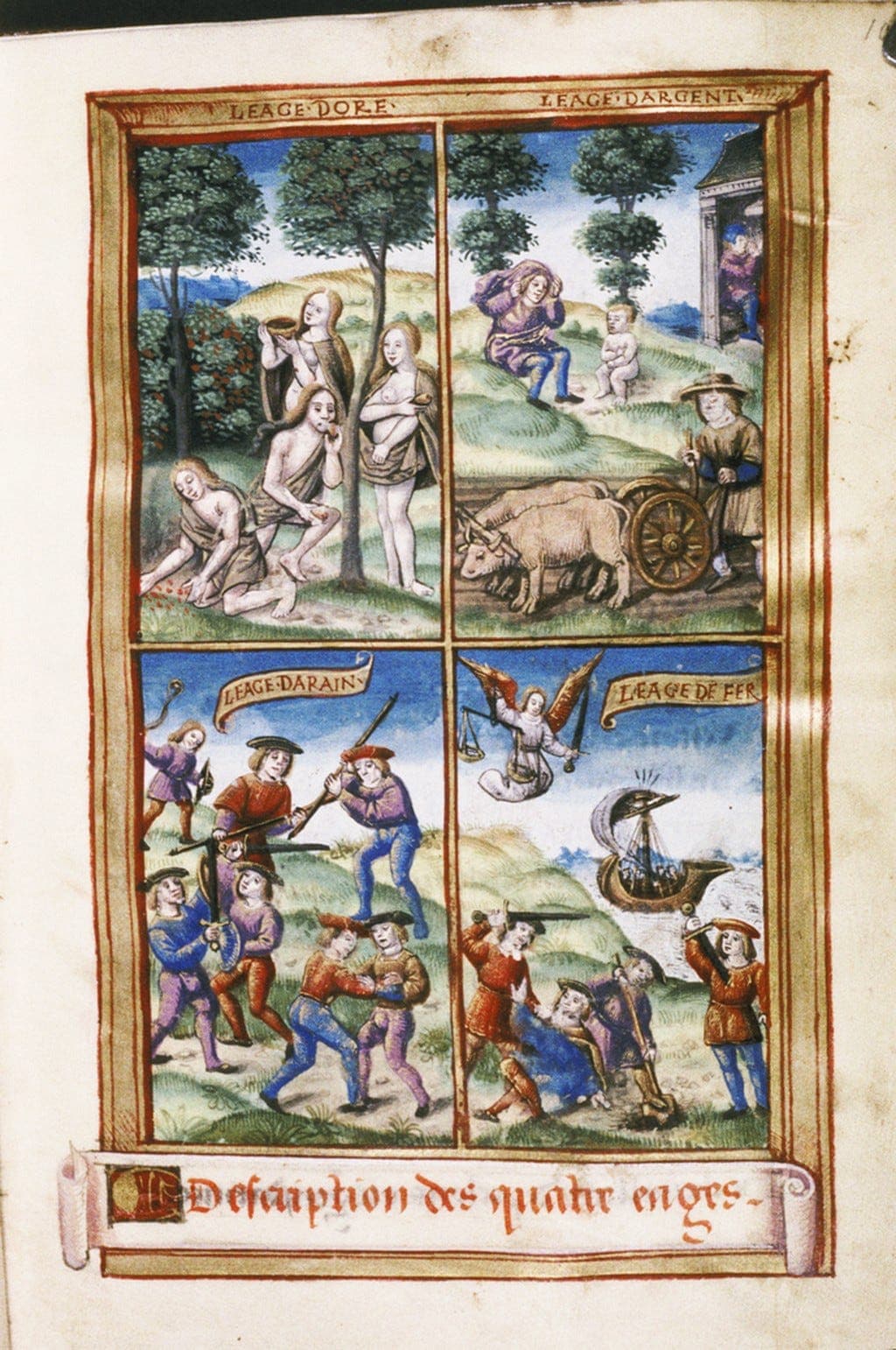

Ovid begins his narration with the primal chaos and the separation of the elements. He goes on to tell us about the earth and the sea, and the five zones, detailing specific regions of the earth. After telling us about the four winds, he moves on to humankind and the four ages of the world, the subject of Dittersdorf’s first symphony.

Scored for flute, pair of oboes, bassoons, horns, trumpets, and timpani, with strings, the first movement introduces as to the time of the golden age. As Ovid writes, “this was the Golden Age that, without coercion, without laws, spontaneously nurtured the good and the true. There was no fear or punishment: there were no threatening words to be read.” In music, this movement is dominated by a serene and tranquil theme that evokes an eternal “Spring with gentle breezes caressing the flowers.”

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 1 in C Major, “The 4 Ages of the World” (Allegro e vivace) (Cantilena; Adrian Shepherd, cond.)

Statue of Ovid

Dittersdorf then moves on to the musical evocation of the silver age. As Ovid tells us, “then came the people of the age of silver that is inferior to gold. Jupiter made the year consist of four seasons, with houses that were first made for shelter. Then seeds were first buried in the long furrows, and bullocks groaned, burdened under the yoke.”

Dittersdorf composes an upbeat movement that follows the sonata-form design. The jolly and busy opening theme quickly turns into a more lyrical contrast played by the string. The wind instrument expands this lyrical idea and a brief development twists around a series of repeated notes. We can certainly tell from the music that humanity is getting busier and busier.

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 1 in C Major, “The 4 Ages of the World” (Minuetto con garbo) (Cantilena; Adrian Shepherd, cond.)

Ovid moves on to the bronze age, “with fiercer natures, readier to indulge in savage warfare, but not yet vicious.” This particular age is musically represented by a graceful minuet, but did you notice that it is scored in the minor key? The minuet proper is rather angular but the trio is smooth and polished. Dark clouds are indeed beginning to descend on humanity.

The concluding movement depicts the age of iron, where “every kind of wickedness erupted and truth, shame, and honour vanished. In their place were fraud, deceit and trickery, violence and pernicious desires.” Dittersdorf immediately paints that wickedness with a tense chromatic figure that opens the movement. As the speed increases we hear a military fanfare and great excitement. There is a short musical respite, but it all ends in restless agitation. Now that’s a great story told in beautiful music.

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 1 in C Major, “The 4 Ages of the World” (Finale: Prestissimo) (Cantilena; Adrian Shepherd, cond.)

The Four Ages

Dittersdorf visited Vienna in 1786 and he received special permission from the Emperor to have six “Ovid” Symphonies performed at an outdoor concert. We know that Baron van Swieten, a close friend and patron of Mozart and Haydn bought a hundred tickets. However, Dittersdorf was unlucky as bad weather threatened the event.

He tried to postpone the concert but had trouble getting permission from the police. So Dittersdorf marched straight to Court to get permission from the Emperor himself. In his autobiography, Dittersdorf gives a detailed account of his visit, and at the end, the Emperor declared that “a short note be written to allow Dittersdorf to postpone his music for as long as he likes.”

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, “The Fall of Phaeton” (Adagio non molto-Allegro) (Cantilena; Adrian Shepherd, cond.)

The second work in Dittersdorf “Ovid Symphonies” musically portrays “The Fall of Phaeton,” son of Helios, the Sun, and Clymene, a mortal. Phaeton has always been curious about his father, and when he is bullied by a friend, he only slightly represses his anger and confronts his mother. “If I am born at all of the divine stock,” he exclaimed, “give me proof of my high birth.” His mother, moved by his plea and anger told him, “By that brightness marked out by glittering rays, I swear to you my son, that you are the child of the Sun… go and ask the sun himself.”

Dittersdorf begins the opening movement with a wonderful musical representation of Ovid’s initial words. “ The palace of the Sun towered up with raised columns, bright with glittering gold, and gleaming bronze-like fire.” What we hear is active syncopation and ornamentation to portray the flickering of the sun, and to tell us that this story will not have a happy ending.

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, “The Fall of Phaeton” (Andante) (Cantilena; Adrian Shepherd, cond.)

The Fall of Phaeton statue, the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Once Phaeton had reached the palace of the sun, the sun looked at the boy and asked him what he wanted. Phaeton replied “Universal light of the great world, give me proof father, so they will believe I am your true offspring, and take away this uncertainty from my mind!” The Sun put aside the shining rays about his head and said, “it is not to be denied you are worthy to be mine, and your mother has told you the truth of your birth.”

In music, this tender moment between father and son relies on a delightful instrumentation as the bassoon doubles the first violin at the octave. The radiant theme is first stated by the violins and subsequently repeated by the bassoon. We also hear some emotional interruptions as the conversation between father and son continues. The music presents us with a very emotional contrast between divine father and mortal son, but the middle section which dips into the minor key, is hinting at troubles to come.

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, “The Fall of Phaeton” (Tempo di Minuetto) (Cantilena; Adrian Shepherd, cond.)

Phaeton, however, is still not entirely convinced and asks his father to grant him a wish. Hardly had the sun settled back in his seat when the boy asked to drive his father’s chariot circling the earth. The father immediately regretted his oath saying, “Your fate is mortal, it is not mortal what you ask.” Eventually, however, he does give in and instruct his son in the impossible task. The father’s regret is musically encoded in Dittersdorf’s minuet.

The story and symphony, almost as expected, ends with the final catastrophe. As Phaeton is guiding the horses, they veer off course and run unchecked into an unknown region. Mountains began to burn and rivers were drying up with the whole earth set on fire. At this moment, Zeus intervenes and hurls his thunderbolt at Phaeton. The music opens in the minor key with much syncopation, and just listen to the dramatic representation of the fall of Phaeton. It all ends subdued as a solar eclipse mourns his loss.

Don’t miss more fanciful stories in music as our next episode will showcase Dittersdorf’s musical tale of “The metamorphosis of Acteon into a Stag,” and “The Rescue of Andromeda by Perseus.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf: Symphony No. 2 in D Major, “The Fall of Phaeton” (Finale: Vivace) (Cantilena; Adrian Shepherd, cond.)