“Before Mozart, all musical ambition turns to despair”

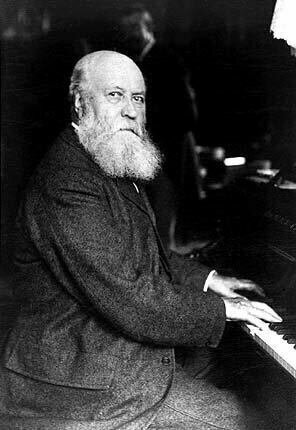

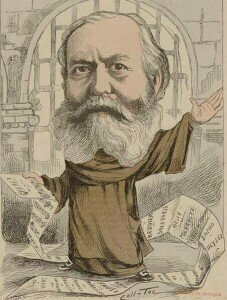

Charles Gounod was born 200 years ago, on 17 June 1818 in Paris. Today we primarily remember him as the composer of the opera Faust and an Ave Maria descant to the first prelude of J.S. Bach’s C-major prelude from the WTC. Yet, during the second half of the 19th century, he was one of the most respected and prolific composers in France. His musical influence on the course of French music was highly significant, but in the fractured post-Wagnerian critical climate towards the end of his life, his reputation took a severe hit. Son of a painter and engraver of considerable talent, Charles exhibited enormous talents in music and the fine arts. Pressured into studying law, Charles decided at age 16 to devote himself to music. Private lessons in counterpoint and harmony with Antoine Reicha prepared Charles for his enrollment at the Paris Conservatoire. Fully devoted to composition, Charles furthered his studies with Halévy and Le Sueur, and he won the Prix de Rome in 1839 with his cantata Fernand.

Charles Gounod was born 200 years ago, on 17 June 1818 in Paris. Today we primarily remember him as the composer of the opera Faust and an Ave Maria descant to the first prelude of J.S. Bach’s C-major prelude from the WTC. Yet, during the second half of the 19th century, he was one of the most respected and prolific composers in France. His musical influence on the course of French music was highly significant, but in the fractured post-Wagnerian critical climate towards the end of his life, his reputation took a severe hit. Son of a painter and engraver of considerable talent, Charles exhibited enormous talents in music and the fine arts. Pressured into studying law, Charles decided at age 16 to devote himself to music. Private lessons in counterpoint and harmony with Antoine Reicha prepared Charles for his enrollment at the Paris Conservatoire. Fully devoted to composition, Charles furthered his studies with Halévy and Le Sueur, and he won the Prix de Rome in 1839 with his cantata Fernand.

Charles Gounod: Fernand

The operatic stage in Rome—primarily populated by Donizetti, Bellini and Mercadante—was of little interest to Gounod. However, coming under the influence of the Dominican preacher Père Lacordaire, Gounod became genuinely fascinated by the music of Palestrina and the cultural legacy of Rome. He also crossed paths with Fanny Mendelssohn, and spent the remainder of his government stipend in Austria and Germany. After meeting with Felix Mendelssohn in Leipzig, Gounod returned to Paris and became music director of the Missions Etrangères church in 1843. He stayed in this position for the better part of four years until he formally enrolled at the seminary of St. Sulpice to begin studies for ordination into the priesthood. In the end, he rather abruptly abandoned his pursuit of the cloth and began to cast his eyes towards the glitzy world of opera.

The operatic stage in Rome—primarily populated by Donizetti, Bellini and Mercadante—was of little interest to Gounod. However, coming under the influence of the Dominican preacher Père Lacordaire, Gounod became genuinely fascinated by the music of Palestrina and the cultural legacy of Rome. He also crossed paths with Fanny Mendelssohn, and spent the remainder of his government stipend in Austria and Germany. After meeting with Felix Mendelssohn in Leipzig, Gounod returned to Paris and became music director of the Missions Etrangères church in 1843. He stayed in this position for the better part of four years until he formally enrolled at the seminary of St. Sulpice to begin studies for ordination into the priesthood. In the end, he rather abruptly abandoned his pursuit of the cloth and began to cast his eyes towards the glitzy world of opera.

Charles Gounod: Messe solennelle de Sainte Cécile

Gounod was not a household name on the Parisian musical scene, but all that changed when he started to orbit around the mezzo-soprano Pauline Viardot. It was her influence that secured him an unexpected commission at the Opéra for Sapho, with a libretto by Emile Augier. In the event, Sapho was an unmitigated failure at the box office, but the work did receive some critical approval from Hector Berlioz. As such, the Opéra offered him another contract in 1852 to set Eugène Scribe’s libretto La nonne sanglante.

Gounod was not a household name on the Parisian musical scene, but all that changed when he started to orbit around the mezzo-soprano Pauline Viardot. It was her influence that secured him an unexpected commission at the Opéra for Sapho, with a libretto by Emile Augier. In the event, Sapho was an unmitigated failure at the box office, but the work did receive some critical approval from Hector Berlioz. As such, the Opéra offered him another contract in 1852 to set Eugène Scribe’s libretto La nonne sanglante.

Additional projects soon followed but Gounod had no great theatrical success until he hit the jackpot with Faust derived from Goethe. Première on 19 March 1859, the opera was once more praised by Berlioz, but casting problems and a hostile press raised doubt whether Faust would be able to survive. Thanks to the efforts of the publisher Antoine de Choudens, who bought the rights and aggressively promoted the work, Faust exploded onto the European opera stages. Richard Wagner called it a “feeble French travesty of a German monument,” but he could not prevent Gounod’s Faust to become the most frequently staged operas of all time.

Charles Gounod: Faust

In the wake of his Faust success, Gounod composed five more operatic works over the next eight years. Mireille, based on a recent epic poem in the Provençal language by Frédéric Mistral of 1864, and the Shakespearean Roméo et Juliette completed in 1867 achieved some level of success, while the other Gounod operas have fallen into oblivion. However, Gounod was sufficiently famous that his name was mentioned in the same breath as Verdi and Wagner. With the declaration of hostilities on 19 July 1870, Gounod moved his family to England to wait for the fall of Paris and the restoration of order. In February 1871 Gounod made the acquaintance of the amateur singer Georgina Weldon, and once his wife Anna had returned to France in a jealous rage, he scandalously took up residence with the Weldons for the next three years. His England interlude was a period of enormous productivity that saw the creation of operatic, religious, and incidental music, as well as over 60 additional songs, duets, and piano pieces. Growing animosity, however, facilitated Gounod’s return to France and a renewed interest in operatic composition. It is fitting however, that Gounod’s greatest public successes in his later career were religious works as the Catholic faith provided Gounod a “stable anchor through the violent emotional swings that beset him throughout his whole life.”

Charles Gounod: Requiem

Gounod died on 18 October 1893, and although Ravel considered him the “real founder of the mélodie in France,” his music fell rapidly out of fashion. Gounod steadfastly believed in a universal dramatic and spiritual truth, and his refusal to pursue the implications of Wagner’s musical style placed him at odds with writers and critics alike. Debussy quipped, “Gounod, for all his weaknesses, was necessary as his art represents a moment in French sensibility.”