Charles Dickens, born on 7 February 1812 on Portsea Island (Portsmouth), Hampshire, is known for creating some of the best-known fictional characters in literature. We all are familiar with Ebenezer Scrooge, Tiny Tim, Little Nell, Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, Samuel Pickwick, and countless others. Regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian era, his works have been highly popular during his lifetime, and throughout the 20th century.

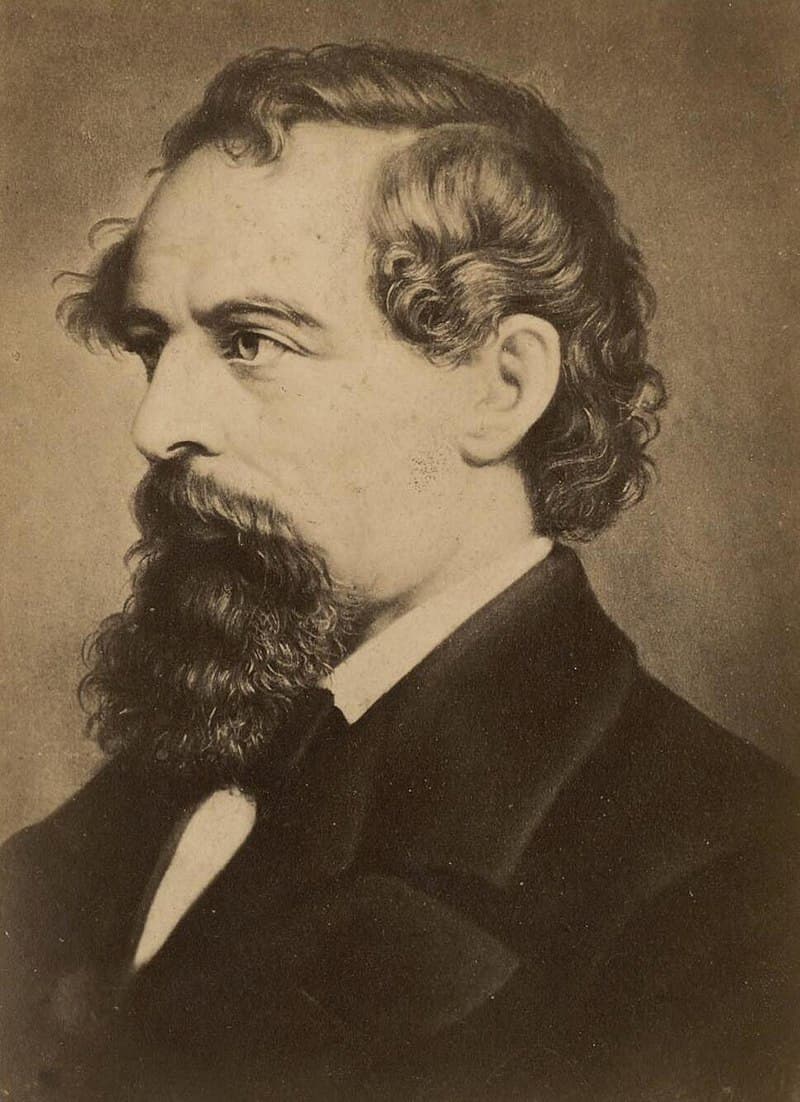

Charles Dickens, 1858

Dickens is considered a literary genius, and musical references appear plentifully throughout his novels and short stories. As his contemporary Thomas Carlyle writes, “I truly love Dickens; and discern in the inner man of him a tone of real Music which struggles to express itself, as it may in these bewildered, stupefied and, indeed, very crusty and distracted days—better or worse!” In his writings, we find the stories of music in the ordinary English home, especially “for the popular songs of period.” Yet, Dickens appears to have been a highly appreciative and critical listener, and he even wrote the libretto for an operetta.

Malcom Arnold: David Copperfield, “Main Title” (Moscow Symphony Orchestra; William Stromberg, cond.)

Charles Dickens’ Music Education

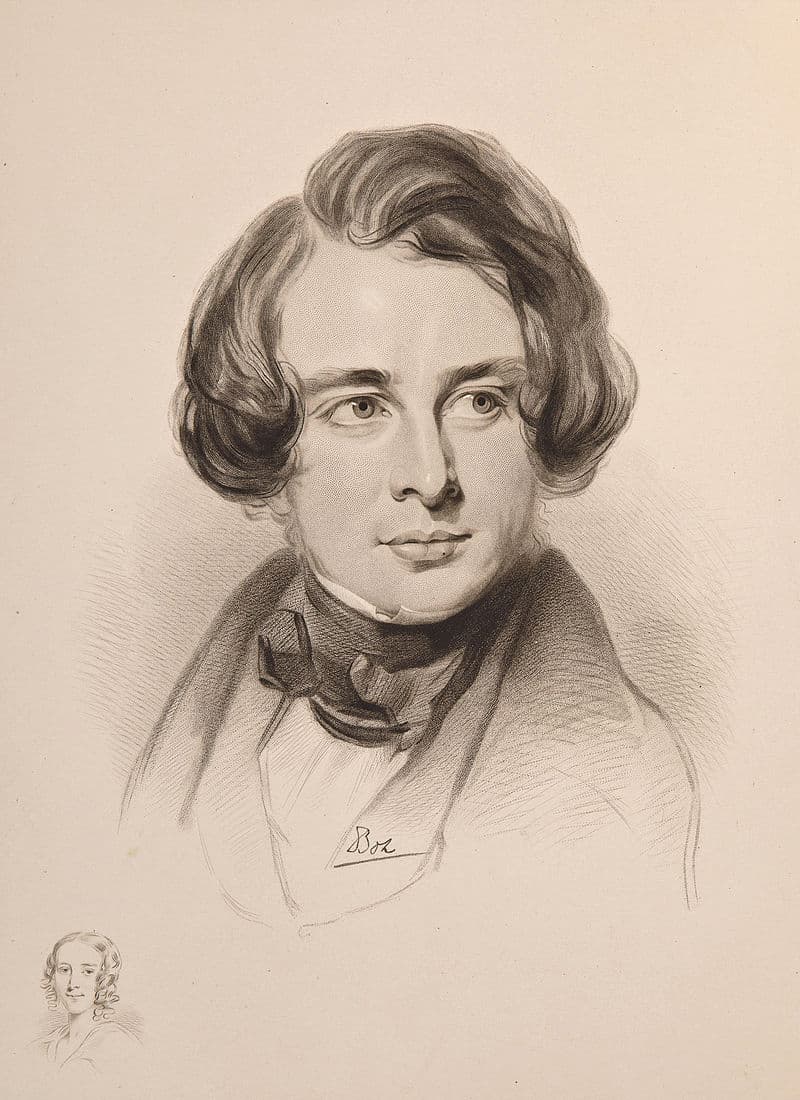

Sketch of Dickens in 1842 during American Tour. Sketch of Dickens’s sister Fanny, bottom left

During his early schooling, Dickens was not particularly interested in music. He initially took piano lessons, but we are told that his “teacher gave him up in despair.” At a slightly later stage, Dickens took violin lessons, but once again made no progress and soon put the instrument aside. At a much later stage in his life, Dickens took a third stab at becoming an instrumentalist, and he bought himself an accordion. On his first voyage to America, “he regaled the ladies’ cabin with my performance. You can’t think,” he writes, “with what feelings I play ‘Home, Sweet Home’ every night, or how pleasantly sad it makes us.” On his return journey, Dickens offers the following description of the musical talents of his fellow passengers. “One played the accordion, another the violin, and another the key bugle: the combined effect of which instruments, when they all played different tunes, in different parts of the ship, at the same time, and within hearing of each other, as they sometimes did, was sublimely hideous.”

Henry Bishop: “Home Sweet Home” (Felicity Palmer, soprano; John Constable, piano)

Favorite Composers

Giacomo Meyerbeer

Clearly, his career as an instrumentalist wasn’t going anywhere, but he did have distinct preferences when it came to music. It is told that Felix Mendelssohn was his favorite composer, closely followed by Chopin and Mozart. During a visit to Paris, he heard Gounod’s Faust, and confessed to having been “quite overcome with the beauty of the music.” In one of his letters he writes, “I just couldn’t bear it and gave in completely. Gounod must be a very remarkable man indeed.” Dickens also knew some music by Offenbach, and he was personally acquainted with Auber. He describes him as “a stolid little elderly man, rather petulant in manner.” And we learn what Dickens thought of Auber’s music in his description of a dinner. “The knives and forks form a pleasing accompaniment to Auber’s music, and Auber’s music would form a pleasing accompaniment to the dinner if you could hear anything besides the cymbals.”

Daniel-François Auber: Le Philtre, “Overture” (Cracow Philharmonic Orchestra; Luciano Acocella, cond.)

Dickens’ Encounter With Meyerbeer and Jenny Lind

Jenny Lind

Dickens met Meyerbeer, and he certainly heard Jenny Lind in concert. Dickens loved to tell an amusing anecdote about Lind. “At a certain German town last autumn there was a tremendous furor about Jenny Lind, who, after driving the whole place mad, left it, on her travels, early one morning. The moment her carriage was outside the gates, a party of rampant students who had escorted it rushed back to the Inn, demanded to be shown to her bedroom, swept like a whirlwind upstairs into the room indicated to them, tore up the sheets, and wore them in strips as decorations. An hour or two afterward a bald old gentleman of amiable appearance, an Englishman, who was staying in the hotel, came to breakfast at the table d’hôte, and was observed to be much disturbed in his mind and to show great terror whenever a student came near him. At last, he said, in a low voice, to some people who were near him at the table, ‘You are English gentlemen, I observe. Most extraordinary people, these Germans. Students, as a body, raving mad, gentlemen!’ ‘Oh, no,’ said somebody else: ‘excitable, but very good fellows, and very sensible.’ ‘By God, sir!’ returned the old gentleman, still more disturbed, ‘then there’s something political in it, and I’m a marked man. I went out for a little walk this morning after shaving, and while I was gone’—he fell into a terrible perspiration as he told it—‘they burst into my bedroom, tore up my sheets, and are now patrolling the town in all directions with bits of ‘em in their button-holes.’ I needn’t wind up by adding that they had gone to the wrong chamber.”

Giacomo Meyerbeer: Robert le diable, “Va, dit-elle, va, mon enfant” (Annalisa Raspagliosi, soprano; Orchestra Internazionale d’Italia; Renato Palumbo, cond.)

Dickens’ Views on Operas and Classical Music

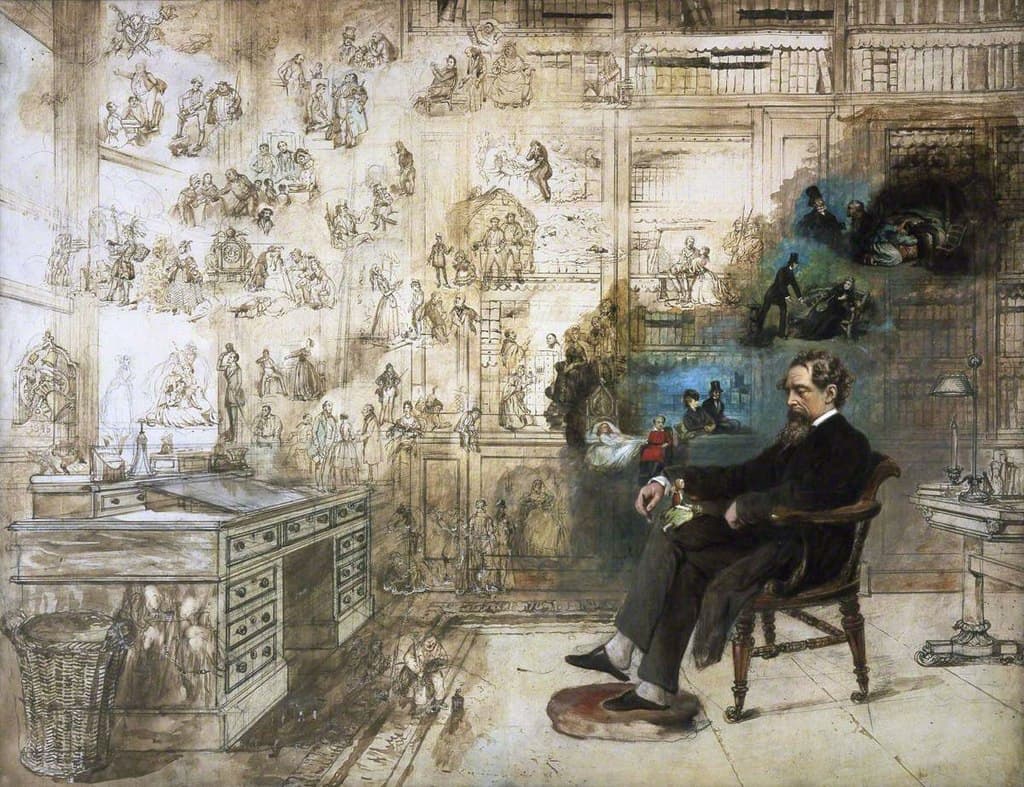

Robert William Buss: Dickens’ Dream

Whenever Dickens spent time on the Continent, he eagerly attended opera performances. As he writes from Carrara, “There is a beautiful little theatre there, built of marble, and they had it illuminated that night in my honour. There was really a very fair opera, but it is curious that the chorus has been always, time out of mind, made up of labourers in the quarries, who don’t know a note of music, and sing entirely by ear.” In his letter to friends and colleagues, Dickens frequently makes references to the music he heard in the streets and squares, including Golden Square in London. “Two or three violins and a wind instrument from the Opera band reside within its precincts. Its boarding houses are musical, and the notes of pianos and harps float in the evening time round the head of the mournful statue, the guardian genius of the little wilderness of shrubs, in the centre of the square… Sounds of gruff voices practising vocal music invade the evening’s silence, and the fumes of choice tobacco scent the air. There, snuff and cigars and German pipes and flutes, and violins and violoncellos, divide the supremacy between them.”

Prince Albert: Melody for the Violin (Iona Brown, violin; Jennifer Partridge, piano)

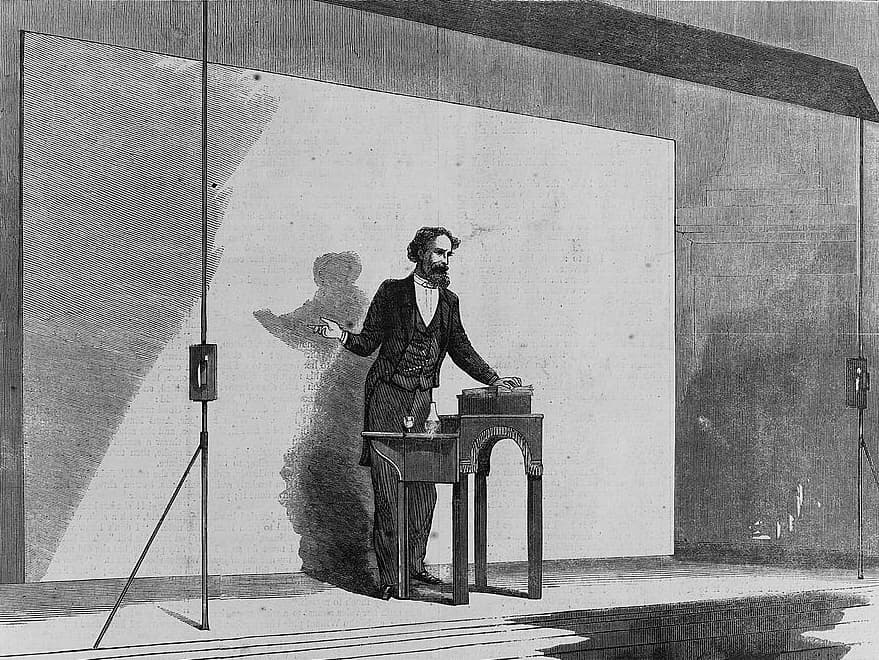

Charles Dickens during a public reading in 1867

Dickens was a keen observer of musical conventions and practices, but he had little to say about the music of his time. However, he strongly condemned the pre-Raphaelites in art, a movement founded in 1848 that sought to imitate early Italian art and was opposed to the classical compositions that made Raphael popular. A similar movement in regard to music was established by the pre-Agincourt Brotherhood, and Dickens writes, “In Music a retrogressive step in which there is much hope, has been taken. The P.A.B., or pre-Agincourt Brotherhood, has arisen, nobly devoted to consign to oblivion Mozart, Beethoven, Handel, and every other such ridiculous reputation, and to fix its Millennium (as its name implies) before the date of the first regular musical composition known to have been achieved in England. As this institution has not yet commenced active operations, it remains to be seen whether the Royal Academy of Music will be a worthy sister of the Royal Academy of Art, and admit this enterprising body to its orchestra. We have it, on the best authority, that its compositions will be quite as rough and discordant as the real old original.”

Eric Coates: The 3 Elizabeths Suite, “Youth of Britain” (New Symphony Orchestra; Eric Coates, cond.)

His Deep Love for Song and Singing

Daniel Maclise: Charles Dickens

Apparently, Dickens had a strong voice and a deep love for song and singing. Critics assume that he had a fine tenor voice, as gleamed from a humorous account of a concert on a journey to Boston. “We had speech-making and singing in the saloon of the Cuba after the last dinner of the voyage. I think I have acquired a higher reputation from drawing out the captain, and getting him to take the second in ‘All’s Well’ and likewise in ‘There’s not in the wide world’ than from anything previously known of me on these shores… We also sang (with a Chicago lady, and a strong-minded woman from I don’t know where) ‘Auld Lang Syne,’ with a tender melancholy expressive of having all four been united from our cradles. The more dismal we were, the more delighted the company was. Once (when we paddled i’ the burn) the captain took a little cruise round the compass on his own account, touching at the Canadian Boat Song, and taking in supplies at Jubilate, ‘Seas between us braid ha’ roared,’ and roared like ourselves.” As J.T. Field observed, “To hear Dickens sing an old-time stage song, such as he used to enjoy in his youth at a cheap London theatre, was to become acquainted with one of the most delightful and original companions in the world.”

Thomas Moore: Irish Melodies, “There is not in the wide world a valley so sweet (John Elwes, tenor; Yoshio Watanabe, fortepiano)

Dickens’ Views on Church Music

While Dickens had little to say about church music in general, he frequently makes reference to the dismal state of church music in England. Surprisingly, when he visited St. Peter’s in Rome, he was also quite unimpressed by the music. As he writes, “I have been more affected in many English cathedrals when the organ has been playing, and in many English country churches when the congregation has been singing.” On a feast day, he attended a service in Genoa and writes, “The organ played away lustily, and a full band did the like; while a conductor, in a little gallery opposite the band, hammered away on the desk before him, with a scroll, and a tenor, without any voice, sang. The band played one way, the organ played another, the singer went a third, and the unfortunate conductor banged and banged, and flourished his scroll on some principle of his own; apparently well satisfied with the whole performance. I never did hear such a discordant din.” Dickens’ only contribution to hymnology, with the title “hymn of the Wiltshire Labourers” appeared in the Daily News on 14 February 1846.

O God, who by Thy Prophet’s hand

Didst smite the rocky brake,

Whence water came at Thy command

Thy people’s thirst to slake,

Strike, now, upon this granite wall,

Stern, obdurate, and high;

And let some drop of pity fall

For us who starve and die!

Arthur Sullivan: “Hearken Unto me, my People” (Constanze Backes, soprano; Passion des Cuivres)

Charles Dickens as an Opera Librettist

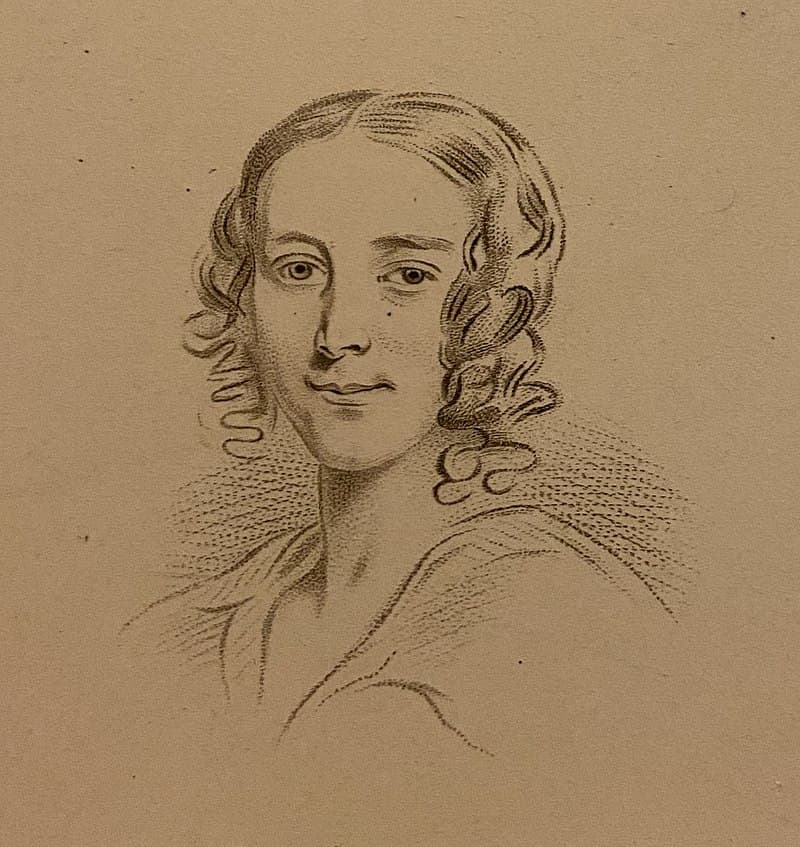

Fanny Dickens

Dickens was said to have been a great actor, a capable stage manager, and he even tried his hands at writing a libretto. His sister Fanny Dickens had been one of the first students admitted to the Royal Academy of Music, and had worked there as a piano tutor. In addition, she frequently returned to the academy to improve her singing and continued to perform at Academy concerts. Her fellow student and concert performer was the aspiring composer John Pyke Hullah. She introduced Hullah to her brother, and by late 1835 they decided to work together on a light opera. Hullah was looking for an Italian piece, but Dickens preferred “the increased ease and effect with which we could both work on an English Drama where the characters would act and talk like people we see and hear of every day. That particular drama was to become “The Village Coquettes.”

John Pyke Hullah: “Three fishers went sailing” (Phillida Bannister, contralto; Fiona Murphy, cello; John Talbot, piano)

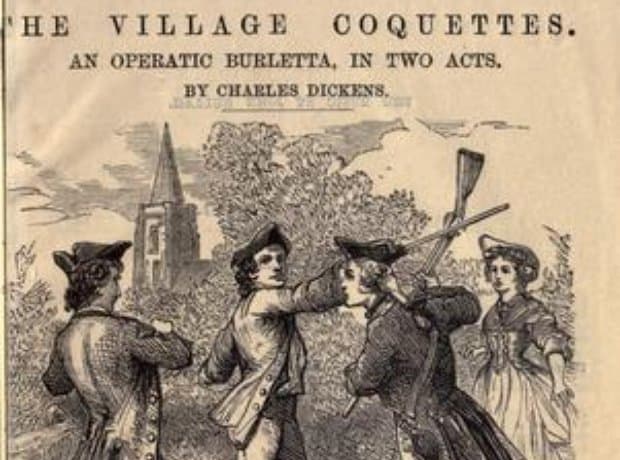

John Pyke Hullah

Much enthused, Dickens completed the libretto in fifteen days, and during a round of revisions added the character Martin Stokes, “a low comedy part without singing.” The premier took place on 6 December 1836, and this historical romance, deliberately written in the style of the minor popular plays of the time, did not catch the public’s fancy. Contemporary critic John Forster writes, “An opera, or as they call it as this house, an operatic burletta, was produced on Tuesday evening…The scene is laid in a country village in England, in the year 1729, and the costume of that day is attempted. The plot and dialogue are totally unworthy of Boz (Charles Dickens). Not to speak of the lack of originality, which this piece presents, it has also the demerit of having the incidents, such as they are, most clumsily hung together… We have now to say a word of the music, and we are compelled to state that its utter insignificance makes our task a brief one… The instrumentation throughout the opera is not appropriate; but the band of this theatre is so inefficient, that it can hardly do justice to any music.”

The Village Coquettes

The critic that night was one of Dickens’s closest friends, the executor of his estate, and his first major biographer. The music for The Village Coquettes consists of songs, duets, and concerted pieces. When the work was performed in Edinburgh in 1837, a fire broke out in the theatre, and all the instrumental scores together with the music of the concerted pieces were destroyed. No new copies were produced, but the songs and Dickens’ libretto did survive.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Arnold Bax: Oliver Twist (Trailer)