Gallica (gallica.bnf.fr), as part of its opera collection, has scenery models (volume models) from three centuries of opera stage construction. These volume models were created after the initial drawings were accepted by the Opera management. The flat drawings are converted to dimensional models at the scale of 3 cm to 1 m. Once this was approved, it was used as the final model.

We were looking at the scenery for the opera Moïse et Pharaon (Moses and Pharaoh) by Giaochino Rossini. A rewrite and reorganization of his 3-act opera Mosè in Egitto of 1818, the new 4-act Moïse et Pharaon was given its Paris premiere in 1827 and another production in 1863 both at the Peletier theatre, the home of the Paris Opéra until the Opera Garnier was built in 1875.

The reason for the biblical storyline was the time of the work’s debut: during Lent, when most secular theatres in Catholic countries were closed for 40 days. In France, which had successfully separated church and state in 1789, secular theatres were open, but the underlying religious faith was served by a new genre of religious melodrama through the early 19th century. With the restoration of the Bourbon monarchs after Napoleon’s fall at Waterloo in 1815 and the restoration of the Catholic Church into power, the Opéra was closed once again during Holy Week. During Lent, however, biblical spectacles were still in fashion and so, three weeks before Easter, on 26 March 1827, Rossini’s Moïse et Pharaon opened.

For the 1827 production, the design was by August Caron (1806–18??) and Pierre Luc Charles Cicéri (1782–1868). When we compare the stage drawings for the 1827 and 1863 productions, we can see an interesting development in stage technology and complexity. There were two different designs for Act I, one by Cicéri and the other by Caron.

Giaochino Rossini: Moïse et Pharaon (1827 Paris version) – Act I: Introduction: Ouverture (Virtuosi Brunensis; Fabrizio Maria Carminati, cond.)

Cicéri: Moïse, Act I, 1827 (Gallica ark:/12148/btv1b70011150)

Auguste Caron: Moïse, Act I, 1827 (Gallica ark:/12148/btv1b7001331s)

In 1863, the scenery was created by Hugues Martin, Charles Cambon, Joseph Thierry, and Edouard Despléchin for a production in Paris at the Académie Impériale de Musique-Le Peletier.

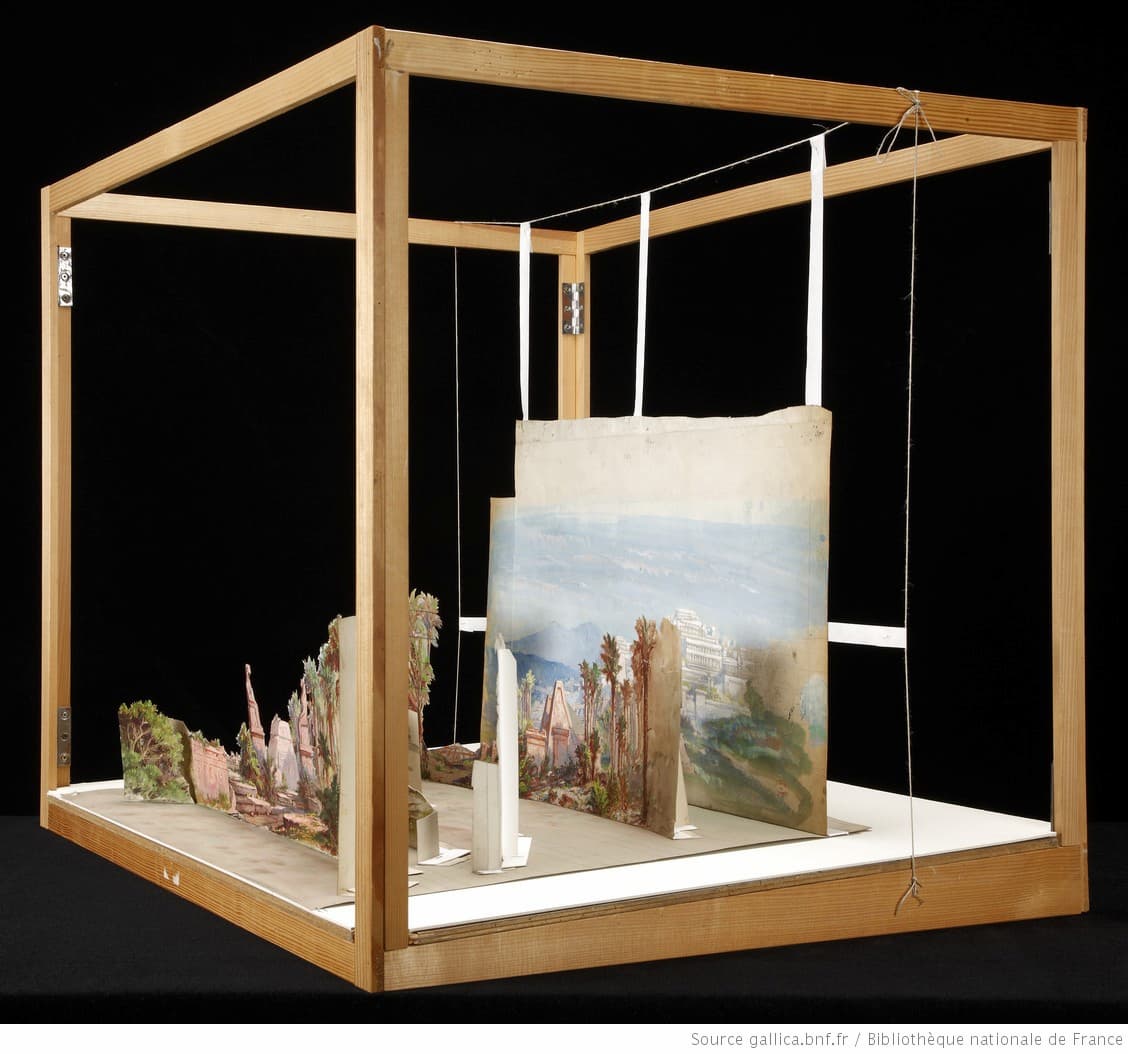

Hugues Martin: Moïse, Acte I: Camp des Madianites sous les murs de Memphis, front view, 1863 (Gallica ark:/12148/btv1b7003327h)

It’s when we see the model from an angle that we can start to appreciate the levels of detail needed for this scene.

Hugues Martin: Moïse, Acte I: Camp des Madianites sous les murs de Memphis, right view, 1863 (Gallica ark:/12148/btv1b7003327h)

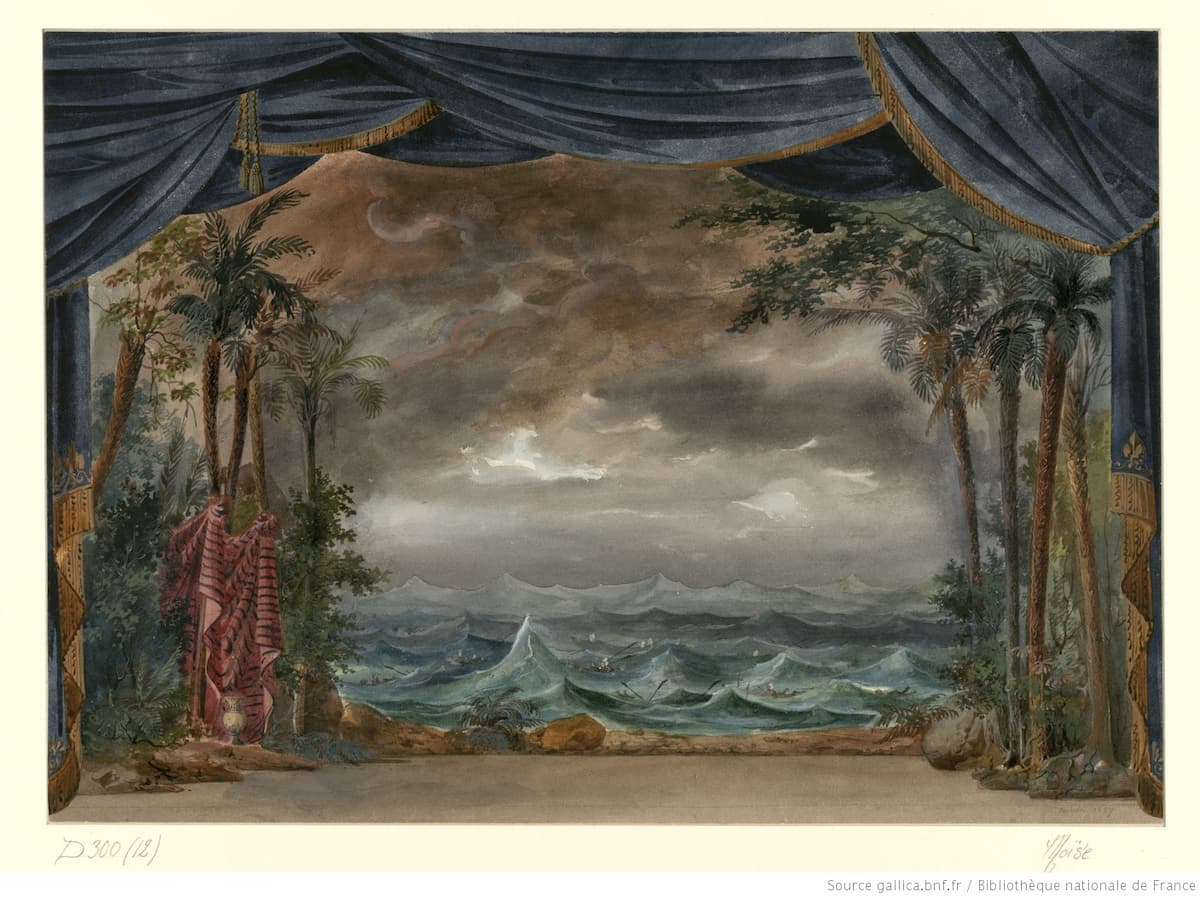

As one might expect, the climax of the opera came in the fourth act, with the Parting of the Red Sea and here we see how the designers imagined this to look. First, there’s the desert, with sand blowing in the background and red fabric tied to the trees, and then there’s the sea, under a turbulent sky. Not shown here was the ending with a vision of Heaven materializing above the Red Sea.

Auguste Caron: Moïse, Act IV, scene i, 1827 (Gallica ark:/12148/btv1b70013341)

Auguste Caron: Moïse, Act IV, scene ii, 1827 (Gallica ark:/12148/ btv1b7001335f)

In Edouard Despléchin (1802–1871), we have one of the most renowned theatre designers in France of his time. In opera, he worked with composers such as Meyerbeer, Verdi, Gounod, and Wagner. For the last, he created the sets for the Paris premiere of Tannhäuser.

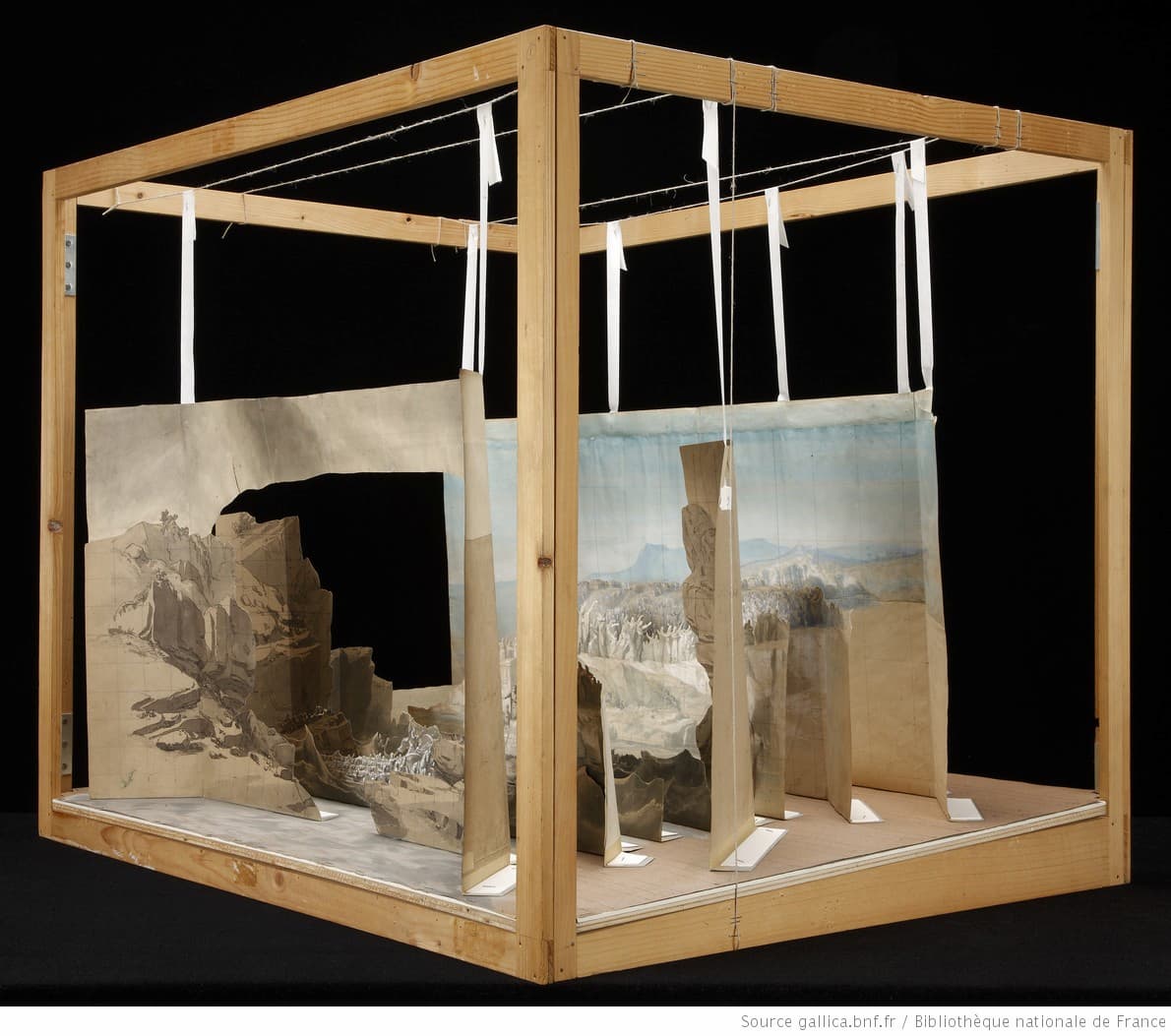

For the final act of Moïse, he sets up a much more dramatic scene. The Hebrews are fleeing, followed by the Pharoah and his troops. The Red Sea confronts them and Moses parts it with a grand gesture. As those fleeing reach high ground, the waves crash back on their pursuers.

Giaochino Rossini: Moïse et Pharaon (1827 Paris version) – Act IV: Scène et Orage: Quel bruit!… (Patrick Kabongo, Éliézer; Albane Carrère, Marie; Elisa Balbo, Anaï; Alexey Birkus, Moïse; Luca Dall’Amico, Pharaon; Randall Bills, Aménophis; Górecki Chamber Choir; Virtuosi Brunensis; Fabrizio Maria Carminati, cond.)

Edouard Despléchin: Moïse, Act IV: Passade de la Mer Rouge, front view, 1863 (Gallica ark:/12148/btv1b7003329b)

When we see this from the side angle, we can see how Despléchin uses the depth of the stage to greater effect, with people on the high ground in the back and foundering in the front.

Edouard Despléchin: Moïse, Act IV: Passade de la Mer Rouge, left view, 1863 (Gallica ark:/12148/btv1b7003329b)

When we look at who, exactly, is caught by the sea in detail, we see it’s the Pharoah’s men, their horses, and battle chariots.

Edouard Despléchin: Moïse, Act IV: Passade de la Mer Rouge, left view center detail, 1863 (Gallica ark:/12148/btv1b7003329b)

The opera ends with a song of praise.

Giaochino Rossini: Moïse et Pharaon (1827 Paris version) – Act IV: Cantique: Chantons, bénissons le Seigneur! (Albane Carrère, Marie; Elisa Balbo, Anaï; Patrick Kabongo, Éliézer; Alexey Birkus, Moïse; Górecki Chamber Choir; Virtuosi Brunensis; Fabrizio Maria Carminati, cond.)

Through these drawings and models, we see how an opera is first changed and revised for the Paris audience (the 1813 3-act becomes the 1827 4-act) and then, in the hands of the designers, the 36 years between productions gave them a chance to expand and dramatize the vision of the composer.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter