We tend to think of the great composers as gods who created their masterpieces in some kind of temple of art.

But in reality, there was no temple, and none of the great composers lived in a vacuum.

All were surrounded by incredibly talented composer colleagues, even if those composers haven’t (yet) joined the established canon.

Johannes Brahms was no exception. He counted a variety of hugely talented composer colleagues as his friends.

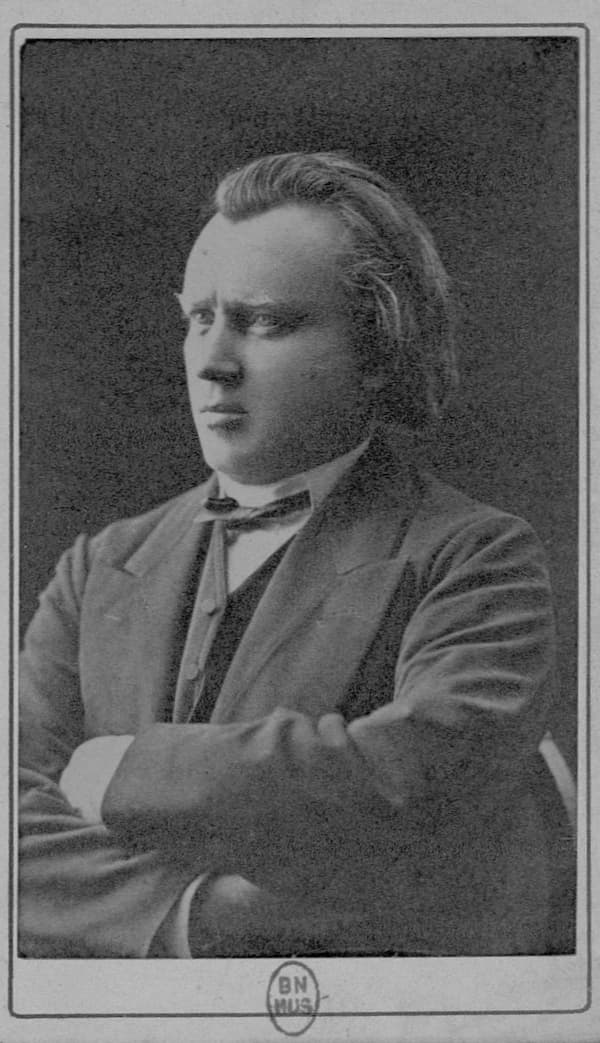

Johannes Brahms in 1872 (Gallica: ark:/12148/btv1b84160058

Today, we’re looking at the music of four of them: Clara Schumann, Joseph Joachim, Heinrich von Herzogenberg, and Elisabeth von Herzogenberg.

All four composers were very different, but their friendship, support, and even criticism all helped to shape Brahms into the towering icon he eventually became.

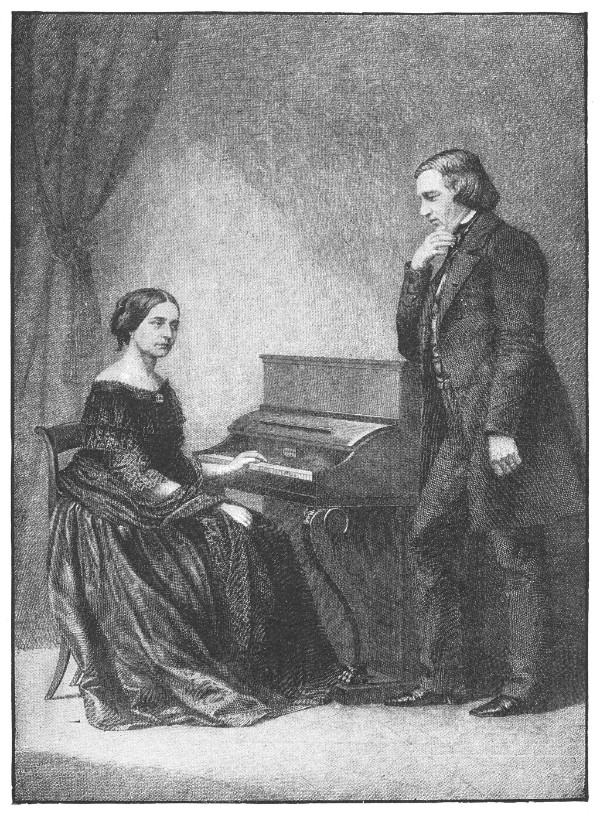

Clara Schumann

Clara Schumann’s Three Romances, written in 1853

October 1st, 1853, was the fateful date that Brahms first met Robert and Clara Schumann in their Düsseldorf home.

Johannes was just twenty years old and looking for mentors, and the Schumanns fit the bill. Robert was 43, while Clara had just turned 34.

Both Schumanns were musical celebrities who could offer Johannes a leg up in the next phase of his career, provided they liked his work. Turns out, they loved his work, and him.

The following year would prove to be a roller coaster ride.

Clara Schumann and Brahms © londonsymphonia.ca

Just weeks later, in late October, Robert published an editorial in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, claiming that Johannes’s “mastery would not gradually unfold but, like Minerva, would spring fully armed from the head of Jupiter.”

Over the winter, Robert’s mental health worsened. In February 1854, he attempted suicide. He agreed to move to an asylum to seek treatment, leaving his distraught wife and children behind.

At the same time, Johannes realised he was falling in love with Clara. He dropped everything and went to be at her side to support her and her children.

Although Clara was best known as a pianist, she was also a composer. In June, a few months before meeting Johannes, she wrote Variationen über ein Thema von Robert Schumann, or Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann.

Clara Schumann’s Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann

Now, during the purgatory of waiting for news about Robert’s health, Clara played Johannes those same variations.

To comfort her and maybe to express his complicated love for her, Brahms also wrote his own set of variations in the summer of 1854. Given all that had transpired in the previous year, and his doomed love for her, they are weightier than hers.

Brahms’s Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann

Robert died in the summer of 1856. Unfortunately for music lovers, Clara drifted away from composing after Robert’s death.

But she did become more and more involved with the creation and promulgation of Johannes’s music, becoming an invaluable inspiration, partner, ally, and sounding board.

Although this set of variations is one of her last compositions, we’re lucky to have it, as well as years’ worth of her pre-1854 compositions to enjoy.

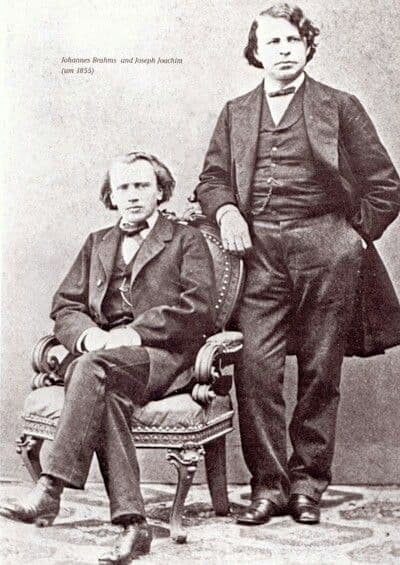

Joseph Joachim

Brahms and Joachim, ca 1855

Joseph Joachim met Johannes Brahms in 1853, when Brahms was on tour accompanying Hungarian violinist Eduard Reményi.

Joachim wrote of Brahms, “I have never before come across so great a talent.” The two would become frequent collaborators in concert.

Joachim was only two years older than Brahms, but by 1853, he had already spent well over a decade performing as a child prodigy.

Eduard Reményi

To Brahms’s delight, Joachim was happy to share his knowledge and connections with Brahms. (It was actually Joachim who provided an introduction to the Schumanns.)

Joachim was the first friend of Robert’s permitted to visit him in the asylum, which he did in December 1854, ten months after Robert’s suicide attempt.

A remarkable Bach recording of Joachim dating from 1903

Joachim composed his second violin concerto, nicknamed In The Hungarian Style, in 1857. Joachim had been born in Hungary and wanted to pay tribute to his heritage in this work.

Joseph Joachim’s second violin concerto, “In the Hungarian Style”

Brahms paid attention to the searing expressiveness and soulfulness of Joachim’s compositions.

Thanks in no small part to his friend’s influence and background, Brahms began embracing “Hungarian” traits in his own music, most famously in his Hungarian Dances.

Brahms’s Hungarian Dance No. 5

And when Brahms went to write his own violin concerto for Joachim in the 1870s, he gave the finale a Hungarian atmosphere…possibly as a winking acknowledgement of Joachim’s own youthful concerto.

Brahms’s violin concerto, third movement

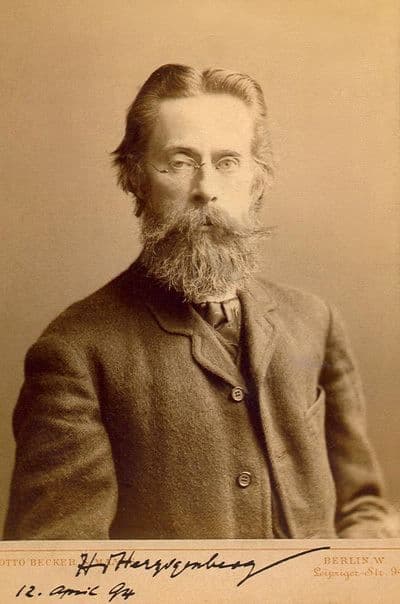

Heinrich von Herzogenberg

Heinrich von Herzogenberg

Heinrich von Herzogenberg was born in 1843, making him ten years younger than Brahms.

He was born to an aristocratic French family who lived in Graz. As a young man, he studied law, philosophy, and politics at the University of Vienna.

However, he was also very musical, and he found himself spending more and more time taking composition lessons.

He became a fan of Brahms’s music and, in 1866, married one of Brahms’s former piano students, the beautiful and talented Elisabeth.

On 1 August 1876, he and Elisabeth both sent Brahms a copy of Heinrich’s Variations on a Theme of Johannes Brahms, each with a cover letter.

Heinrich von Herzogenberg’s Variations on a Theme of Johannes Brahms

In her letter, Elisabeth wrote:

Our friend Bertha assures me that you sent us kind messages and expressed, at the same time, a wish to see Heinrich’s Variations on a Theme by Brahms. I am only too delighted to believe both her assertions.

Heinrich did not want to bother you with the variations… But your kindness in expressing the wish alters the case.

I hope you will not entirely disapprove of the piece, but if it should have the misfortune to displease you, do not hesitate to say so. For ‘as the heart panteth after the water-brooks,’ so panteth Heinrich after honest criticism, be it condemnatory or flattering.

Brahms never was completely sold by his eager acolyte’s output, and his opinion of these variations was no exception. Twenty days later, in his response, Brahms wrote:

My dear friends –

Most sincerely do I thank you for the gift, I might almost say the advertisement, of your Variations.

It is really most gratifying to find a song of one’s own absorbing another person’s thoughts so effectively.

You must have some affection for the melody you choose for a theme, I take it, and in your case, the affection was probably shared by two.

But forgive me if my thanks begin, and my critical remarks end, sooner than you would like.

Despite the awkwardness of that first exchange, it served as the starting point of a deeply rewarding friendship. The Herzogenbergs would become some of Brahms’s most treasured confidants throughout the 1870s and 1880s.

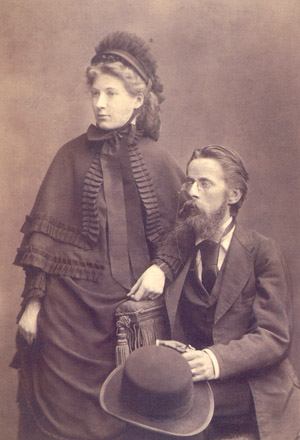

Elisabeth von Herzogenberg

Elisabeth von Herzogenberg

Elisabeth von Herzogenberg was born Elisabeth von Stockhausen in Paris in 1847 to a musical diplomat and his wife. (Her father had studied with Chopin.)

In 1853, the family moved to Vienna. Elisabeth began studying piano at the Vienna Conservatory with Julius Epstein. Epstein was well-respected as a teacher in Vienna; years later, he would teach Gustav Mahler.

After he moved to Vienna in 1862, Brahms became Elisabeth’s teacher for a brief time. He found her attractive; in addition to her astonishing musical abilities, she was also beautiful and charismatic. That attraction may have been one reason why he ultimately urged her to return to Epstein.

She married Heinrich von Herzogenberg in 1868. According to composer and memoirist Ethel Smyth, the couple was unable to have children. Perhaps as a result, they channeled their nurturing energy into their art and social circle.

Brahms’s friends the Herzogenbergs

In 1876, in her first letter reconnecting with Brahms, while sending along Heinrich’s Variations on a Theme by Brahms, she wrote:

Last of all, let me ask if the idea of visiting Leipzig again ever crosses your mind? You did not have such a bad time before, and you know how many devoted friends you have here in spite of all the philistines – bother them!

In case you do come again, I have a real favour to ask: that you should stop at the Herzogenbergs’ instead of at Hotel Hauffe.

I promise you a bed at least as good, much better coffee, no very large room but two decent-sized ones, a silken bed-cover, any number of ash-trays, and, above all, peace and quiet; while, as a set-off against the gilt and stucco and all the glories of the Hauffe establishment, we would make you real comfortable, refrain from worrying you, and only make you realize the great pleasure you were giving us. Think it over!

Such a relaxed and sincerely welcoming attitude proved to be an irresistible temptation for Brahms.

Although he never particularly warmed to Heinrich’s music, he came to value the couple’s artistic opinions deeply, and Elisabeth’s in particular…so much so that he kept her picture framed on his writing desk.

In 1880, he dedicated his passionate Two Rhapsodies, Op. 79 to her.

Johannes Brahms: 2 Rhapsodies, Op. 79

He also sought out her advice on other major works of his, such as his fourth symphony. He began relying on her opinions so extensively that Clara Schumann became jealous.

Brahms was devastated when Elisabeth, who had always struggled with heart issues, died of them in 1892.

He wrote to her widower: “You know how unutterably I myself suffer from the loss of your beloved wife, and can gauge accordingly my emotions in thinking of you, who were associated with her by the closest possible human ties.”

After her death, Heinrich submitted eight of her pieces for piano for publication. It is believed that these, along with a set of 24 folksongs for children, are her only compositions that survive today.

Elisabeth von Herzogenberg’s 8 Clavierstücke

After Elisabeth’s 1892 death, Brahms’s music became increasingly autumnal. Clara Schumann died in May of 1896, and Brahms in April of 1897.

Learn more about Brahms’s relationship with Elisabeth von Herzogenberg.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter