Johannes Brahms was born in 1833 in Hamburg, Germany. He ended his life one of the undisputed giants of nineteenth century music.

Here are a few facts about his life and music:

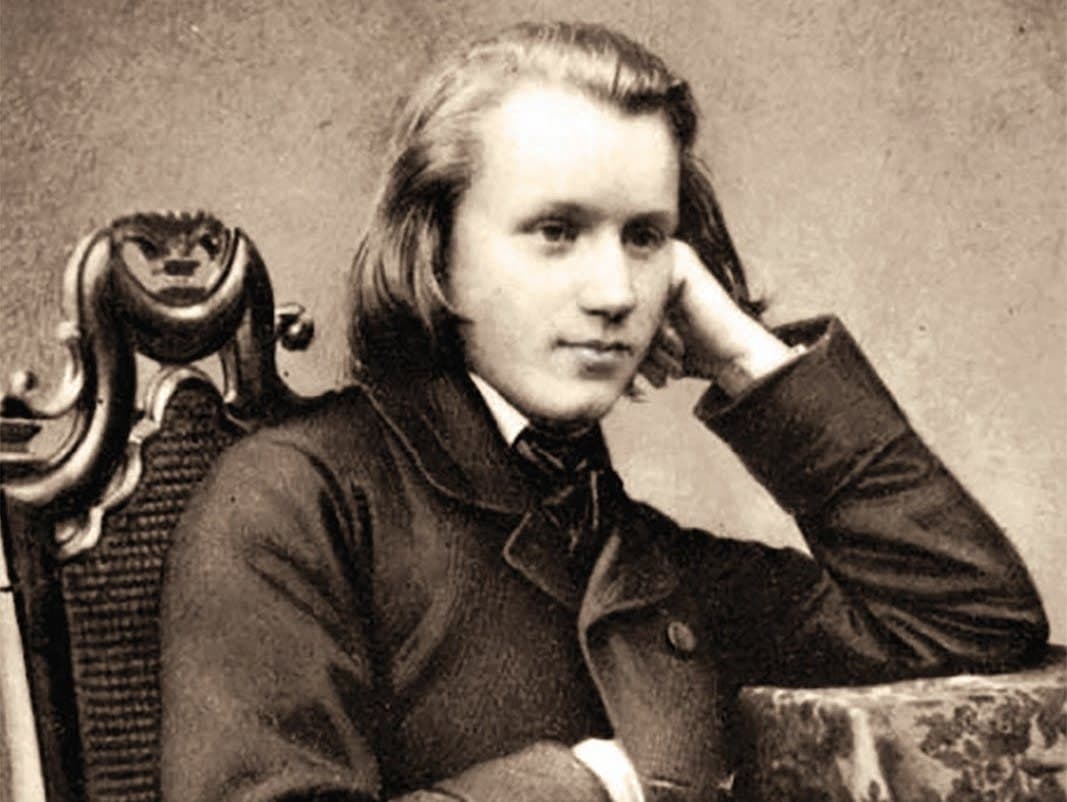

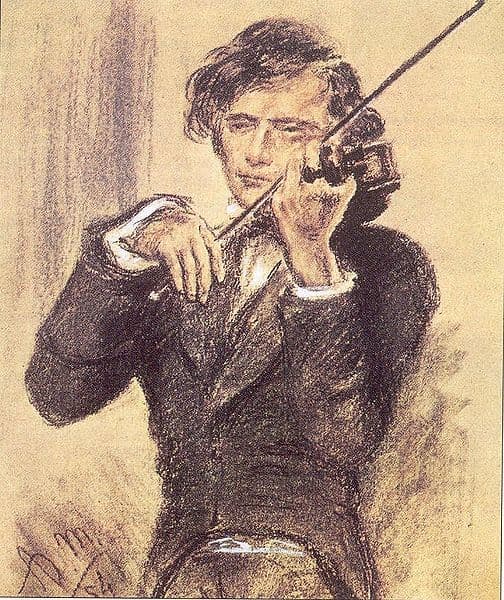

Johannes Brahms, 1853

- Brahms spent his career caught up in an important aesthetic battle known as the War of the Romantics.

One side believed that music should embrace the new, move on from the old, focus on building bridges with other art forms, and generally discard the idea of music for music’s sake.

The other – Brahms’s side – believed that new music should look to traditions of the past for inspiration and focus on music for music’s sake, without relying on extra-musical links to poetry or visual art.

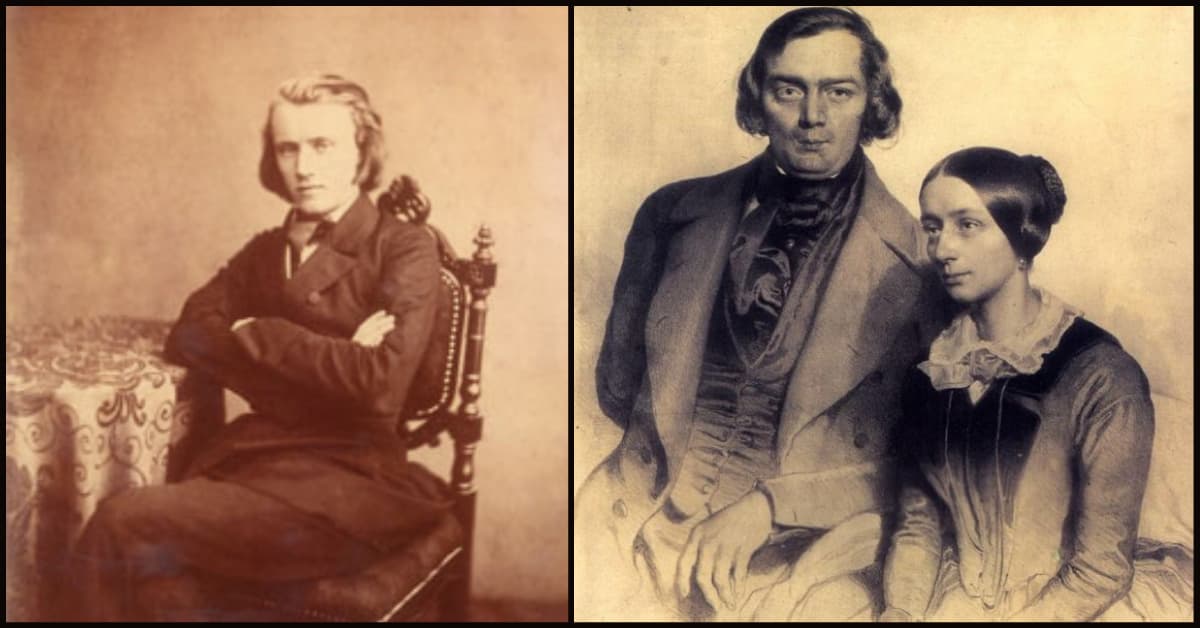

Brahms believed that a work for orchestra alone using traditional templates could be just as important and affecting as an avant-garde opera, and he was determined to prove it. - The most influential personal and professional relationship of Brahms’s life was with a pianist and composer named Clara Wieck Schumann.

They met in the 1850s when she and her husband, composer Robert Schumann, both became his mentors. Messily, he fell in love with Clara, who was widely considered to be one of the greatest pianists of her generation.

Unfortunately, Robert Schumann suffered from severe mental illness, possibly bipolar disorder. After Robert moved to an asylum and died, Brahms stayed near Clara for a while to help her and her young children.

Although Brahms and Clara Schumann never got married, for decades they worked together closely, constantly exchanging musical ideas, and loved each other dearly until the end of their lives. - Brahms also had a long-lasting friendship with a violinist named Joseph Joachim. That said, it had its rocky patches! But this relationship appears again and again in his work.

- Brahms chose to never marry or have a family, and he channeled all of his energy and emotion into his compositions. He was also a noted perfectionist who destroyed many of his earliest works and who curated his correspondence, always keeping an eye on future generations.

Many people noted his gruff exterior. But that gruff exterior hid a deeply emotional man who wrote incredibly touching, beautifully restrained, meticulously crafted music.

Intrigued? Hope so! Here are twelve pieces by Brahms to get you started:

Piano Concerto No. 1 (1854-58)

Brahms came to meet the Schumanns in 1853, when he was only twenty years old. (His friend Joseph Joachim had provided the letter of introduction.) The couple immediately took him under their wing and encouraged him to write a big work like a symphony.

The young Johannes Brahms and the Schumanns

Months after that first meeting with Brahms, Schumann had a severe mental health episode and tried to commit suicide. Schumann asked to be taken to an asylum, and he was. Tragically, he never recovered. He died in 1856, but not before he wrote an influential article claiming that Brahms was going to be the savior of music and win the War of the Romantics.

That pressure was a lot for someone barely in his twenties. But Brahms had no other choice but to try to ignore the weight of the expectations and keep composing.

The first orchestral work of Brahms’s career was not a symphony, as the Schumanns had hoped. Instead, it was his first piano concerto, which is deeply wistful and dramatic and touches on the emotions brought about by his association with the Schumanns. It also pays tribute to Beethoven in the final movement, which copies the structure of the finale of Beethoven’s third piano concerto.

Audiences were initially unconvinced by this work. It would take more music from Brahms and more championing by Clara Schumann to secure its place in the repertoire. But it was an important first step in his career.

Hungarian Dances Book 1 (1858-68)

Brahms began work on a symphony in 1854, but the continued pressure ultimately stifled his creativity.

Years before he ever came out with a symphony, he released this set of Hungarian dances for piano four-hand. They proved to be incredibly popular and earned him a lot of money: always good news for a young composer!

Ein deutsches Requiem (1865-68)

With “Ein deutsches Requiem” (“A German Requiem”), Brahms gained valuable experience writing for orchestra.

It has been theorized that Brahms was inspired to write the Requiem after the death of his mother in 1865 (although he later said that was not the case).

He also continued to draw on thoughts and feelings about Robert Schumann’s tragic death, weaving in music that he’d written around the time of Schumann’s departure for the asylum.

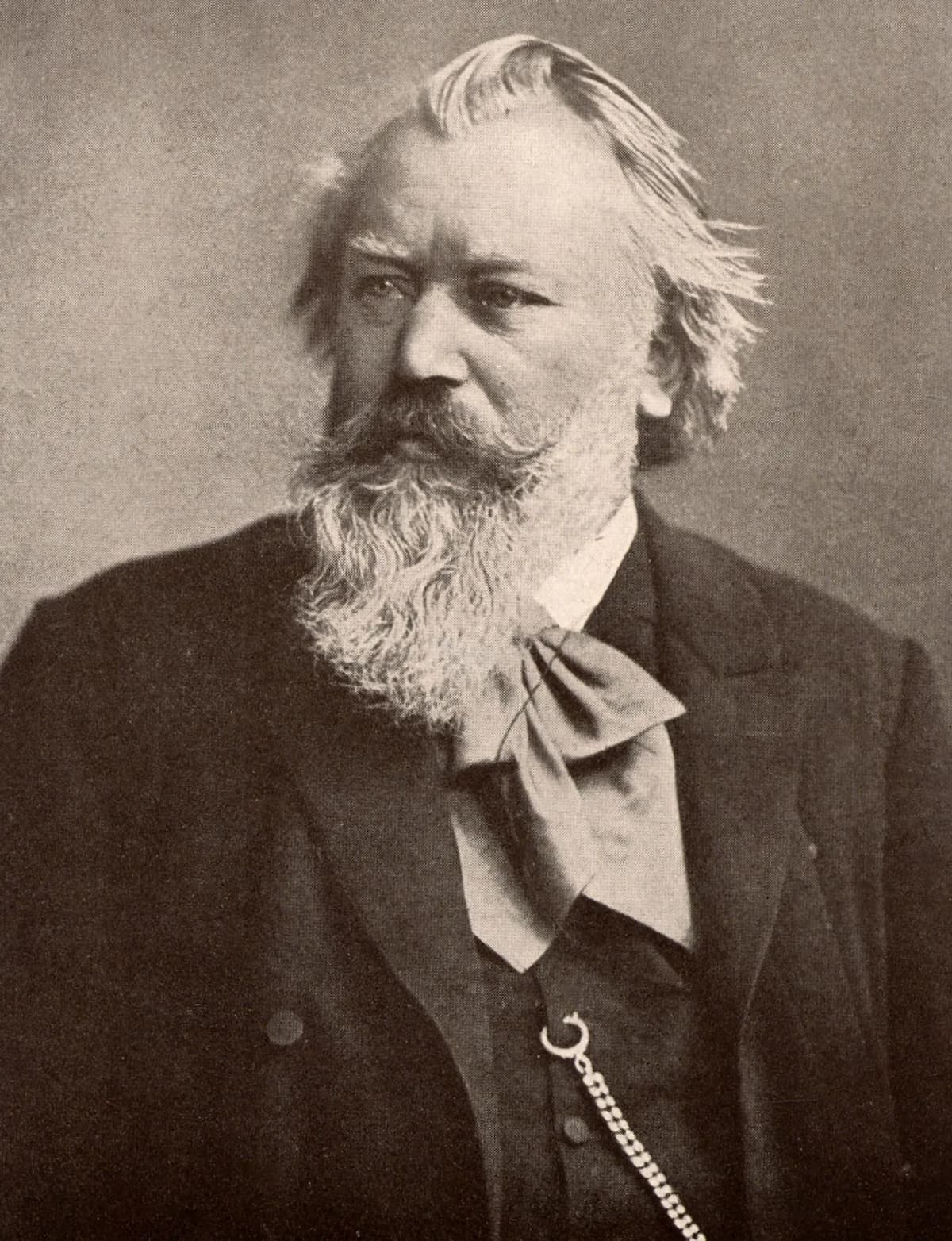

Johannes Brahms

This is a deeply personal Requiem. Staunchly German and from a working-class Lutheran background, Brahms ignored the words of the Catholic Requiem Mass, instead opting to create his own libretto (or script). Accordingly, the work steers clear of Christian dogma and is heavy on humanism. This didn’t go over well with some of his more religious friends and acquaintances.

Wiegenlied (1868)

You probably know this one! It’s commonly known as the Brahms Lullaby today.

This gentle, tender song for voice and piano was composed for a friend named Bertha Faber, whom Brahms had once been in love with.

In the score, he included a countermelody from a song she used to sing to him. This charming – if perhaps slightly odd? – gesture was indicative of Brahms’s lifelong awkwardness around women who weren’t Clara Schumann.

Variations on a Theme by Haydn (1873)

By the early 1870s, Brahms had been a professional composer for twenty years…but he still hadn’t written his long-awaited symphony!

He did, however, bury himself in composing a set of variations on a classical-era theme “by Haydn.” Later historians discovered that this theme was not actually by Haydn, but never mind: Brahms’s astonishing treatment of it makes its origins irrelevant and lifts the simple theme to rarified creative heights.

This work was originally written for two pianos, but he soon arranged it for orchestra. That orchestral arrangement is absolutely first-rate. There are so many colors and layers and subtleties to marvel over and enjoy.

In the 1860s and 1870s, his rivals in the War of the Romantics were linked to a very different style of music known as “Music of the Future,” so Brahms’s very pointed turn to the past for inspiration made quite the statement.

Piano Quartet No. 3 (1875)

By 1875, Brahms was finally close to finishing the symphony he had begun over twenty years before.

Accordingly, he was drawing from his previously written music – and his memories of the past – when writing this beautifully romantic piano quartet.

He wrote a cryptic note to his publisher about this piece. It has a sarcastic tone to it, but one can feel emotional truth resonating from it:

“On the cover, you must have a picture, namely a head with a pistol to it. Now you can form some conception of the music! I’ll send you my photograph for that purpose. You can use the blue coat, yellow breeches, and top boots since you seem to like color-printing.”

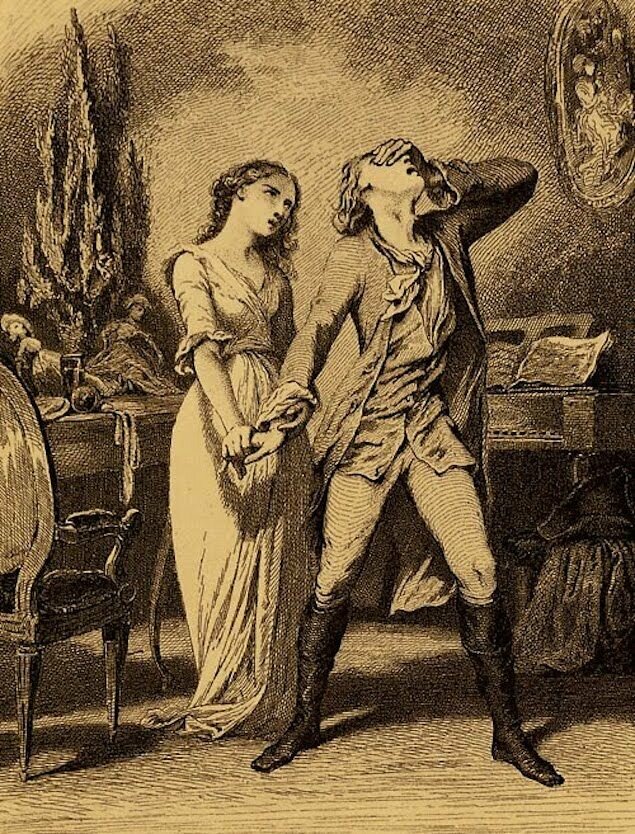

This is a reference to Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, a story in which a sensitive artist named Werther falls in love with a married woman. (Sound familiar?)

The Sorrows of Young Werther

In the novel, Werther believes that for the trio to find happiness, one of the three must die. Werther chooses to sacrifice himself, to the great grief of the married woman. Feel free to draw whatever conclusions you’d like from that!

Symphony No. 1 (1854-76)

Finally, the big day came: 4 November 1876, the day of the premiere of Brahms’s first symphony. Was it a hit or a miss?

According to influential critic Eduard von Hanslick, it was a decided hit:

“Seldom, if ever, has the entire musical world awaited a composer’s first symphony with such tense anticipation… The new symphony is so earnest and complex, so utterly unconcerned with common effects, that it hardly lends itself to quick understanding…[but] even the layman will immediately recognize it as one of the most distinctive and magnificent works of the symphonic literature.”

Indeed, the work is dense, and the emotions expressed in it can often feel repressed or understated. However, its sheer beauty is instantly recognizable, and repeated listens will help audiences hear the passionate heartbeat of this work that lies just beneath its brilliant craftsmanship.

It may have taken two decades, but with this first symphony, Brahms fulfilled the prophecy of the Schumanns.

Violin Concerto (1878)

Now that he’d written a great symphony, Brahms, ever conscious of the past and his place in history, decided that he wanted to burnish his legacy by composing a violin concerto, too. Most of the “great composers” have composed at least one.

Joseph Joachim, 1853

Brahms, however, was not a violinist; he was a pianist. So he turned to his old friend Joseph Joachim for help. With their busy schedules, the two weren’t able to work face-to-face, so they sent their notes to one another via the mail. Somehow, they were able to make the collaboration work.

The program at the premiere was pointed. Joachim insisted that the first half of the concert contain Beethoven’s violin concerto, and the second half contain the premiere of the Brahms violin concerto. It was a not-very-subtle announcement to the world that the legacy of German music was alive and well, and that Brahms was the man safeguarding its legacy.

Audiences were perplexed by the piece, and many violinists of the era actively disliked it. It actually took a new generation of champions – who, coincidentally, were mostly women soloists – to advocate for this muscled marathon of a concerto. It remains one of the most physically and emotionally demanding in the repertoire even today.

Academic Festival Overture (1880)

In 1880, the University of Breslau informed Brahms that they were awarding him an honorary doctorate. There was an insinuation attached that he’d be expected to accept in-person and compose something suitably high-brow and grand as a thank-you. Brahms, prickly with strangers, felt resentment.

The way he solved the problem was iconic. When he arrived in Breslau, he came with an ironic thank-you in hand: a distinguished concert overture…consisting of arrangements of rowdy, bawdy college drinking songs.

Symphony No. 4 (1884-85)

Luckily, Brahms’s next symphonies didn’t take twenty more years to write. He came out with his second in 1877, his third in 1883, and his fourth in 1885.

By this time, he recognized that he was likely nearing the end of his life and career. He was also increasingly aware that there was not a single standout composer to whom he could hand the baton of German music like Schumann had done to him. It was becoming possible that his beloved tradition might die out upon his death.

He had these things in mind when he wrote his fourth symphony. He worked hard to balance emotion and intellect and did so exquisitely. In the last movement, he used an old form called a passacaglia, often employed by German Baroque composers like Bach and Handel. He also leaned heavily into feelings of poignancy and tragedy. The symphony ends on a cataclysmic note.

2 Songs for an Alto Voice with Viola and Piano (1884)

These might just be two of the most beautiful works in Brahms’s entire output. They were written for Joseph Joachim and his wife, contralto Amalie Joachim, and have a deeply poignant backstory.

The second of the two songs was originally composed for the Joachims’ 1863 wedding. But Brahms, ever the perfectionist, held it back until the birth of their first son (who was named Johannes, after Brahms).

When the Joachims’ marriage began breaking down, Brahms tried to help in the best way he knew how: by creating music for the two to make together. So he resurrected this work, rewrote it, and added a second song to the set in 1884.

However, the Joachims’ marriage was broken in a way that a well-meaning friend could not fix. In the end, not even Brahms’s glorious music could save a doomed relationship. The Joachims ended up parting ways bitterly.

Intermezzo in A-major from Six Pieces for Piano, Op. 118 (1893)

Fortunately, Brahms’s musical partnership with Clara Schumann was still going strong. That said, by the 1890s, she was feeling her age. She had developed arthritis in her hands that often made playing piano difficult.

Clara Schumann

Brahms, however, could not fathom a life not writing music for her, and so he wrote a series of shorter, introspective piano pieces and dedicated them to her.

The set ended up being one of the last piano works that Brahms ever wrote.

In 1894, the two legendary musicians met briefly in Frankfurt, and she played selections for him that, according to her daughter, moved them both to tears. “Your mother has been playing most beautifully for me,” he said. After one last shared joke, they parted. They’d never see each other again.

Conclusion

Clara Schumann died in the spring of 1896.

Within the year, Brahms was diagnosed with terminal cancer. He went to his last concert – a performance of his fourth symphony – on 7 March 1897. Brahms died on April 3rd.

The great composers are often put on pedestals or, alternately, viewed as stiff stodgy old men. But even as he has been by turns idolized or dismissed, the undeniable fact remains that, as much as he might have hated it, Brahms was an especially human composer.

He was full of deep hidden emotions, prickly sarcastic humor, intense passion for his art, and loyalty to the talented friends who stayed by his side.

Because of the many layers to his personality and his work, there is always more to learn about when it comes to Brahms’s music and his world.

If you’re intrigued, check out our Brahms tag.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter