It was just Orthodox Easter Eve and all over Greece, the church bells rang out at midnight. We were thinking about music with bells and all the different ways that they are used.

They’re used in a couple of different ways. One is for celebration, another is to show the time, and others are to symbolize church ceremonies. Let’s take a look at this!

One of the most memorable uses of bells for celebration is the wild ringing of bell at the end of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture where the bells of Moscow ring out celebrating the defeat of Napoleon’s army.

Adolph Northen: Napoleon’s Retreat from Moscow, 1851

In this recording by the Philadelphia Orchestra, this happens at (14:45).

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: 1812 Overture, Op. 49 (Mormon Tabernacle Choir; Valley Forge Military Academy Band; Philadelphia Orchestra; Eugene Ormandy, cond.)

But, when we think of what resources are available to a symphony orchestra, a full set of church bells is rarely included. For their 1958 stereo recording, the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra under Anatol Doráti, made a separate recording of the bells at Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial Carillon, at Riverside Church, in New York. The cannon, by the way, were recorded at West Point using a French Napoleonic-era single muzzle-loading cannon. The bells enter at 12:45 and what a difference in sound, given that this carillon, with 72 bells is the second largest int the world.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: 1812 Overture, Op. 49 (Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra; University of Minnesota Brass Band; Antal Doráti, cond.)

At the end of Mussorgsky’s grand procession around his friend Victor Hartmann’s art show in Pictures at an Exhibition, the Great Gate of Kiev, the bells of the tower enter at the end.

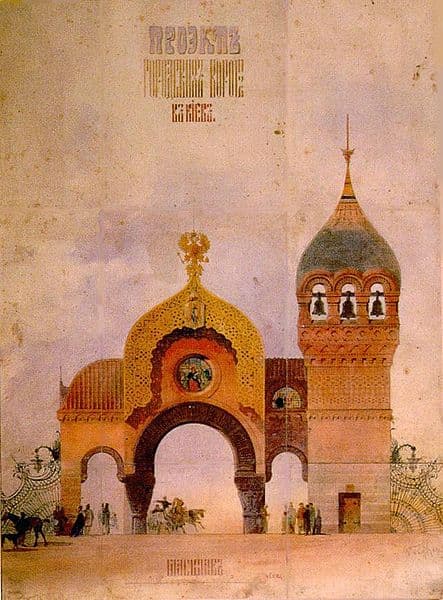

Victor Hartmann: Plan for a City Gate in Kiev, 1869

(Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkin House))

Modest Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition (arr. P. Breiner for orchestra) – X. La grande porte de Kiev (The Great Gate of Kiev) (New Zealand Symphony Orchestra; Peter Breiner, cond.)

As played out in the village square on Easter morning, the opera Cavalleria Rusticana takes place with the church as the backdrop. After the mid-opera Interlude, the next scene begins with church bells, as the villagers leave church to go home for Easter dinner.

Pietro Mascagni: Cavalleria Rusticana – Scene – Chorus: A casa, a casa, amici (Giacomo Aragall, Turiddu; Anna di Mauro, Lola; Slovak Philharmonic Chorus; Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra; Alexande Rahbari, cond.)

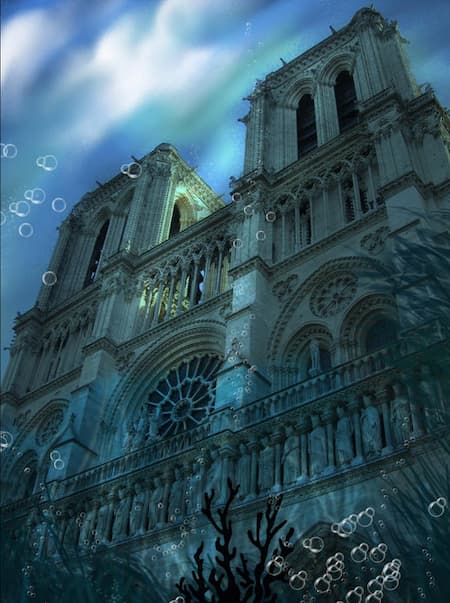

In Debussy’s Préludes, Book 1, the tenth work, La cathédrale engloutie, is about the fabled sunken city of Ys that rises up from the waters on clear mornings when the water is transparent. The opening, with stark open chords, invokes the sound of the church bells as the cathedral remerges out of the water.

Kuru-da-Bunbun: Cathedrale Engloutie, 2007 (Deviantart.com)

Claude Debussy: Préludes, Book 1 – No. 10. La cathedrale engloutie (Carol Rosenberger, piano)

In its orchestral arrangement, here done by Leopold Stokowski, the bell sounds are crystallized.

Claude Debussy: Préludes, Book 1 – No. 10. La cathédrale engloutie (arr. L. Stokowski for orchestra) (Philharmonia Orchestra; Geoffrey Simon, cond.)

Estonian composer Arvo Pärt created his work Darf ich… as a piece for violin, bells and strings. Originally written in 1995 and then revised in 1999, the work has a curiously church-like feel from the use of the bell in a work that would not normally have percussion. The bell, pitched in C sharp, is to be played ad libitum, that is, at the player’s will.

Arvo Pärt: Darf ich … (Gidon Kremer, violin; Kremerata Baltica; Gidon Kremer, cond.)

And as you can hear, these two performances use the bell in different ways.

Arvo Pärt: Darf ich … (Renaud Capuçon, violin; Lausanne Chamber Orchestra; Renaud Capuçon, cond.

Sleigh bells can only signal snow, and horses, and holiday time, as Leroy Anderson’s Sleigh Ride tells us. Note the bells around the waists of Currier and Ives’ horse.

Currier and Ives: The Road – Winter, 1853

Leroy Anderson: Sleigh Ride (BBC Concert Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond.)

The use of the bell to show time can be heard in the final movement of Hector Berlioz’ Symphonie fantastique, where, part-way through the wild witches’ sabbath (05:23), the bell to mark the hour starts to ring – and if you count them…you’ll realize it’s 11 pm. Berlioz, ever the pragmatic orchestrator, said that if it were not possible to get enough low bells (he’s scored it for 3 Cs and 3 Gs, played in octaves), one could double the low notes with a piano or two. The bells are to be placed off stage, so that the audience cannot see them being played.

Francesco Goya: Witches’ Sabbath, 1797-98 (Madrid, Museo Lázaro Galdiano)

Hector Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14 – V. Songe d’une nuit de Sabbat: Largo – Allegro – Dies Irae – Ronde du Sabbat – Dies Irae and Ronde du Sabbat together (Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra; Roger Norrington, cond.)

The bells, bells, bells, bells, as Edgar Allan Poe says in his poem The Bells. In his poem, the bells signify sledges in the snow, with the bells on the horses, the mellow wedding bells, the loud brazen alarm bells, and the tolling of bells at night. In music it can mean all that and more – setting scenes, telling us the time, and signaling celebrations.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter