The series of short and evocative solo piano works by Alexander Scriabin titled “Poèmes” span much of his compositional career. Composed between 1903 and 1915, these pieces became vehicles for expressing discrete poetic moods. Varying in mood and complexity, the poèmes convey profound emotional or philosophical ideas within a miniature form.

Alexander Scriabin

These works remain a cornerstone of Scriabin’s piano oeuvre, celebrated for their technical demands and spiritual resonance. Essentially, they showcase the composer’s shift from Romantic lyricism to a more atonal and experimental style.

Employing rich harmonic textures and emotional depth that often evoke imagery or spiritual concepts, the poèmes for solo piano evoke a unique and otherworldly quality, bridging Romantic traditions with modernist innovation. To commemorate Scriabin’s death on 27 April 1915 at the age of 43, let us briefly explore 10 of these evocative scores.

Deux Poèmes Op. 32

Composed during a transitional period in Scriabin’s career, Op. 32 reflects his deepening interest in poetry, philosophy, and mysticism while retaining the influence of Chopin, Liszt, and Wagner. Composed in 1903, these poems move away from the conventional tonality of his earlier works and towards a more chromatic, harmonically ambiguous style.

The title immediately suggests an intimate and lyrical form, and hints at an idea behind the music. However, as an early Scriabin biographer writes, “they should not be considered programme music but rather a realisation in sound of a certain experience.”

The Deux poèmes of 1903 are counterparts, the first introverted and dreamily passionate, the second outgoing and challenging. To scholars, they reflect “Scriabin’s increasing concern with the concept of self-assertion,” as the archaic and solemn expression “I am” occurs early in a notebook.

Scriabin seemed to have had a strong attachment to Op. 32, No. 1, a piece he often played in recitals and one he also recorded on a piano roll. This poème has no accompanying poetry, but it was contemporaneous with the Fourth Sonata in the same key, and “a score to which, for the first time, Scriabin attached a literary program.”

Poème Tragique Op. 34

Around 1903, Scriabin was navigating a number of personal and professional changes. He had recently left his teaching position at the Moscow Conservatory to focus on composition and was grappling with his growing interest in philosophical and mystical ideas. And, according to Faubion Bowers, “Scriabin was also working on a philosophical opera.”

In fact, he wrote the text for the opera intermittently, using the protagonist of a philosopher-musician-poet to deliver his philosophical thoughts on the power of will, the power of one to create, and his opposition to religion. As such, the Poème, Op. 32, No. 2, and the “Poème Tragique,” Op. 34, are part of this specific operatic fabric.

Both are filled with restless energy, chromatic harmonies, and dramatic contrasts that create a vivid narrative of struggle and resolution. The work certainly strikes a heroic pose, with the middle section presenting an “angry, proud” theme that introduces an element of foreboding. Scholars have also noted that the “downward thematic contour of this section anticipates the “theme of protest” in Le poème de l’extase.

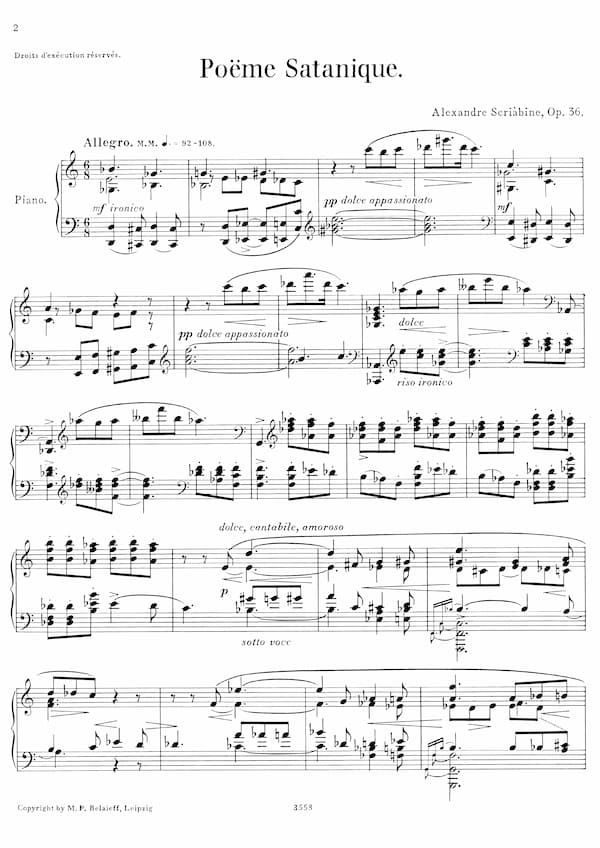

Poème Satanique Op. 36

As Ampai Buranaprapuk suggested, the “Poème Satanique” has “at least roughly, a narrative.” The title advises the devilry of Satan, recalling a poem from Baudelaire’s work Les Fleurs du mal. However, as Scriabin explained, this piece “isn’t true evil. It is an apotheosis of insincerity. Everything in it is hypocritical and false… Satan is not really himself there. He’s just a little devil…”

Scriabin’s Poème Satanique

Musically, we clearly sense the influence of Liszt, with the sensual chromaticism of the 1st “Mephisto Waltz” seemingly evoked. Scriabin assigns specific words to the score, with a “dolce appassionato” juxtaposed by a “riso ironico.”

These markings recur throughout the score in various guises, and the overall structure resembles a rondo form. As Buranaprapuk writes, “it is not a miniature, but a series of discrete episodes.” Scriabin’s harmonies are richly chromatic, with frequent use of altered chords and modulations that destabilise the tonal centre. The “Poème Satanique” concludes with a triumphant, almost mocking flourish, reinforcing its bold and provocative character.

Deux Poèmes Op. 44

Alexander Scriabin: Deux Poèmes, Op. 44 (Dmitri Alexeev, piano)

By 1905, Scriabin had relocated first to Geneve and Vésenaz, and subsequently to Bogliasco, a little south of Genoa. He had started a close relationship with Tatyana Schloezer, and gotten to know the theosophical writings of Helena Blavatsky.

As he wrote to a friend, “I am finally situated in conditions which not only do not hinder me from concentrating and working, as was the case nearly all my life, but which calm the imagination and free its wings.”

The Two Poèmes Op. 44, reflects his evolving musical language and philosophical worldview during this transitional period. The mark is a bridge between the Romantic lyricism of his youth and the post-tonal works of his maturity. Both “Poèmes” retain a tonal framework but push toward atonality through intense chromaticism and whole-tone harmonies. Situated at a crossroads in his career, “they offer a glimpse into the cosmic aspirations that defined his later works.”

Poème Languide Op. 52, No. 3

The “Poème languide” dates from the summer of 1905 and was commissioned by Gabriel Pierné for his magazine L’Illustration. The editor asked “Scriabin for a little melody to be published in autograph form. Initially, Scriabin submitted a “Romance,” which was rejected because readership was not used to songs expressing complicated emotion.”

As such, Scriabin wrote this one-page poem, which he subsequently included as the third piece of the Three Pieces Op. 52. The melody recalls that of Op. 41, “with the same three-note motif that Scriabin repeats so often in the earlier work.”

This Poème follows a loose and through-composed form, with a single melodic idea unfolding over shifting harmonies. Lacking strong cadences, Scriabin enhances a sense of suspension, as if capturing a momentary vision. Harmonic ambiguity and compact form align with mystical undertones that explore the composer’s introspective side.

Poème-Nocturne Op. 61

Alexander Scriabin

Alexander Scriabin: Poème-Nocturne, Op. 61 (Garrick Ohlsson, piano)

In the piano poems of his maturity, Scriabin abandons tonic endings and goal-directed functional harmony. The mystic or “Prometheus” chord becomes prominent, and according to Taruskin, Scriabin called this chord “the chord of the pleroma.” In essence, Scriabin uses this chord to portray something outside the human realm.

The Poème-Nocturne dates from 1912, and compared to most of the other poems, it is a large-scale work. Exploring the mystic chord and subsets of the octatonic scale, Scriabin musically encodes his belief in art’s power to evoke cosmic unity.

This poem is ethereal, introspective, and sensuous as it evokes a dreamlike atmosphere. An almost improvisatory quality conveys a sense of spiritual yearning, and the harmonic language creates a floating, ambiguous soundscape. In terms of form, Scriabin transcended sonata form as he once remarked, “I at last managed to transcend the realm of human emotion.”

Deux poèmes Op. 63

Faubion Bowers describes the Deux poèmes, Op 63, as satanic. “They invoke evil’s deceptive, illusory world,” with the subtitles as well as the expressive markings recalling “Satan’s insincerity and deceptiveness. As such, they evoke the sentiment previously explored in the Poème satanique.”

Both poems were composed immediately after the composer had finished his Sixth and Seventh Sonatas with “mystery” as the main extra-musical theme. The concept of mysteriousness appears as “Masque” in the title of Op. 61, No. 1, with his radical harmonic innovations and mystical aspirations distilled into miniature forms.

Enigmatic and playful, “Masque” offers a capricious and almost theatrical quality. Relying on the “mystic chord” and whole-tone elements, this poem unfolds as a single thematic idea via rapid changes of mood. In “Étrangeté”, the mood is restless and unsettled, with the frequent use of tritone relationships creating a sense of unease and mystery.

Deux poèmes Op. 69

Alexander Scriabin’s Two Poèmes, Op. 69, composed in 1913, are late-period piano miniatures that exemplify his mature, highly chromatic, and mystical style. These works, both untitled but marked “Andante” and “Allegretto,” reflect Scriabin’s theosophical worldview and his push toward atonality, coming just two years before he died in 1915.

Both Poèmes are exceedingly brief and showcase Scriabin’s ability to convey profound ideas in miniature form. Highly chromatic, rhythmically fluid, and technically demanding, they require nuanced control from the performer.

No. 1 is lyrical and introspective, with a serene yet elusive quality. Its flowing, almost improvisatory melody evokes a sense of longing or spiritual contemplation, “floating in a dreamlike haze.” By contrast, No. 2 is more dynamic and capricious, exuding a restless and almost playful energy. These brief poems are profound expressions of Scriabin’s vision of music as a transcendent force, making them essential to understand his late oeuvre.

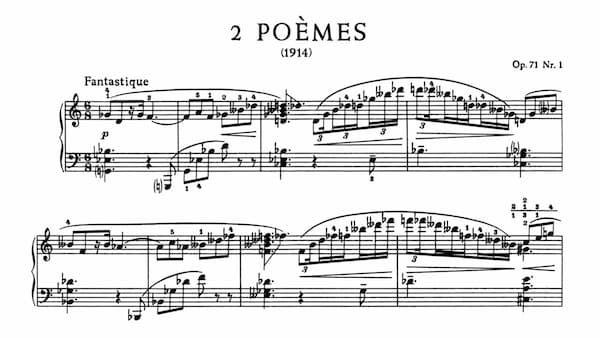

Deux poèmes Op. 71

Scriabin’s Deux poèmes Op. 71 No. 1

Alexander Scriabin: Deux poèmes, Op. 71 (Lucille Chung, piano)

In his Deux poèmes, Op. 71, composed in 1914, the mystic chord serves not only as a harmonic entity but also as a structural principle. Its permutations underpin melodic motifs, accompanimental figures, and climactic moments, creating a sense of unity despite the music’s apparent freedom.

Scriabin associated specific colours with musical keys and harmonies, believing that music could evoke visual and spiritual experiences. As scholars have written, the “lush, dissonant harmonies in Op. 71 might be seen as evoking shades of violet or indigo,” colours Scriabin linked to mystical states.

Op. 71 shares a nocturnal warmth that is not heard anywhere else, except perhaps in passages from the works of Mahler and Schoenberg. The first poem, titled “Fantastique”, is similar in musical language to that of early Alban Berg, while No. 2, entitled “En rêvant”, takes Chopin as a reference. Scholars write, “it is not confessional art, as there is no sense of offering a melodramatic glimpse into a precious, private personality. Rather, it is a fine product of a highly original, cosmopolitan composer.”

Vers la flamme “Poème” Op. 72

The young Vladimir Horowitz

Vladmir Horowitz played for Scriabin at the age of 11, and subsequently became one of the major proponents of his music. According to Horowitz, the title “Vers la flamme” (Towards the flame) related to the composer’s conviction that the world as a whole was edging “toward the flame and would gradually heat up until it erupted into a fiery cosmic conflagration.” Apparently, Horowitz added, “Scriabin was crazy, you know.”

Subtitled “Poème”, the music is limited to an obsessively repeated semitone motif announced at the opening. Interspersed with impressionistic representation of fire, represented by a unique harmonic vocabulary of altered chords and tritones, the piece communicates through a gradual increase in complexity and animation of the texture. And just listen to the final burst of bright light at the extreme end of the keyboard.

The evolution of Alexander Scriabin’s musical language in his twenty piano poems mirrors the characteristics of symbolist poetry, a trend also evident in his other genres. Composed between 1903 and 1915, the poèmes are a series of evocative miniature pieces that often carry extramusical associations inspired by his philosophical ideals. The Poèmes are celebrated for their technical demands and emotional depth, offering performers freedom for personal expression while showcasing Scriabin’s harmonic innovations.

While his music is beautiful and his influence undeniable, his work is a paradox. It is exhilaratingly original yet occasionally overwrought. After all, a harmonic revolution had already taken place in Vienna, and the stunning atmospheres he created had long been seen in Paris. A scholar writes, “Scriabin did achieve a sublime balance of intellect and emotion, but his excesses risk alienating listeners.”

Without the lofty messianic aura and the ardent support it has inspired among his disciples, where would the core and influence of his music truly stand?

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter