Our popular series forgotten cellists from 2018 continues with several outstanding artists you may not know of.

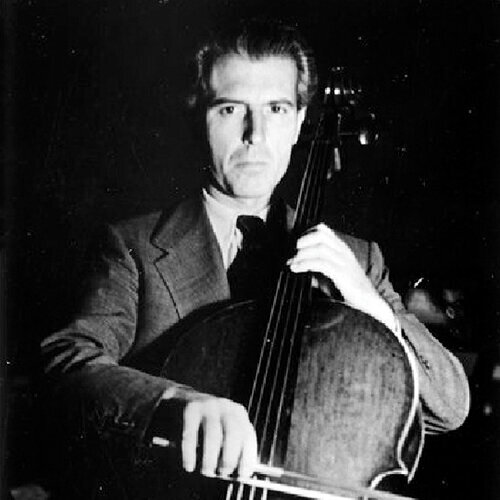

Harvey Shapiro

One-thousand students claim cellist Harvey Shapiro the “cello doctor” was the single greatest influence in their lives. The esteemed pedagogue taught at Juilliard for more than three decades. But he had an amazingly varied career before he was invited in 1970 to teach at the Juilliard School in Leonard Rose’s stead while the latter took a sabbatical to tour with the Istomin-Stern-Rose trio. Shapiro stayed on and indeed taught into his 90s. He had an uncanny ear, wonderful technique, and, as one of his famed students James Kreger said, “the unique ability and deep knowledge of human psychology amplified by…the gift of being able to get inside the psyche of the student and find a way to ignite the spark that lights the path to improvement and mastery.”

Robert Schumann: Fantasiestücke, Op. 73 (version for cello and piano) (Harvey Shapiro, cello; Hiroko Komoriya, piano)

Word got around. Other instrumentalists took advantage to listen in on lessons and reveled in Shapiro’s wisdoms.

Born in New York in 1922 of Russian parentage, he demonstrated his affinity for the cello very early. At age eight he was invited to study with the esteemed pedagogue Julius Klengel in Leipzig, but the family couldn’t afford to send Harvey to Germany. After living on the west coast, they moved back to New York. Barely able to make ends meet, the family had to live in frigid flats, so Harvey would be able to study with Dutch cellist Willem Willeke—known as the “Dutch Casals” at the Institute of Musical Art (which became the Juilliard School). Imagine. Willeke had played for and with Brahms.

Born in New York in 1922 of Russian parentage, he demonstrated his affinity for the cello very early. At age eight he was invited to study with the esteemed pedagogue Julius Klengel in Leipzig, but the family couldn’t afford to send Harvey to Germany. After living on the west coast, they moved back to New York. Barely able to make ends meet, the family had to live in frigid flats, so Harvey would be able to study with Dutch cellist Willem Willeke—known as the “Dutch Casals” at the Institute of Musical Art (which became the Juilliard School). Imagine. Willeke had played for and with Brahms.

After Shapiro won the Naumberg competition and the Morris Loeb prize in 1937, maestro Arturo Toscanini invited Shapiro to join the NBC orchestra. It was fortuitous. There he met several outstanding artists. Partnering with violinist Joseph Gingold, and pianist Earl Wild, they formed the NBC Trio. Shapiro also became a member of the Primrose String Quartet, one of the leading chamber ensembles of the 20th century, with Gingold, violist William Primrose, and violinist Oscar Shumsky. Their rehearsals were made easy considering Shapiro, Gingold, and Primrose lived in the same building in New York. NBC radio broadcast the quartet’s live performances each week, and their fame spread. Sadly, due to the intervention of World War II, the group parted ways before they were able to complete the project of recording the entire cycle of Beethoven String Quartets.

© Stewart Pollens

The war intruded in Chicago too. Principal cello Frank Miller left the Chicago Symphony to enlist. Toscanini invited Shapiro to lead the CSO cello section, which he did for three years. After the war Shapiro became an active chamber musician and studio player. Several of the prominent maestros of the day: Szell, Reiner, Beecham, Stokowski and others, invited Shapiro to play principal cello for their orchestras. In the 1950’s the Metropolitan Opera engaged Shapiro to play the exposed cello solos in their opera recordings. Shapiro also played the eloquent and heartbreakingly beautiful cello solo in the Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2 with legendary pianist Arthur Rubinstein, Josef Krips at the helm, recorded after midnight at the Manhattan Center in New York. James Kreger tells us, “When the movement concluded John Pfeiffer, one of RCA’s most highly regarded producers, called out a robust “Bravo!” over the PA system…” and everyone congratulated Shapiro for his divine playing of the melody, done in one take!

Johannes Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-Flat Major, Op. 83 – III. Andante (Arthur Rubinstein, piano; RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra; Josef Krips, cond.)

But Shapiro was no stranger to adversity. During the depression, he struggled to support his family and was very fortunate to land a job playing at Radio City. Later in life he suffered from physical ailments including severe arthritis, deteriorating eyesight, and a bout with cancer, but none of these prevented him from performing into his tenth decade.

An old-school style teacher, he could be irascible, critical, demanding, and known to spew choice profanities. The characteristic Havana cigar hanging from his lips, and a glass of fine scotch nearby, his goal was always for the student to “fully realize their potential” whatever it took. On the other hand, Shapiro was extremely generous with his time and attention, and dedicated to his students, even loaning his superb Mateo Goffriller cello when a student needed a great instrument for an important audition or performance.

Although many of his recordings are out of print, Shapiro’s deep warm sound, exquisite vibrato, and flawless technique is evident in the recordings we can still listen to including a wonderful recording of Rachmaninoff sonata with Earl Wild, pianist, and a live performance from Carnegie Hall in 1966 of Ernest Bloch Schelomo: Rhapsodie Hébraïque for Violoncello and Orchestra with Stokowski conducting.

Shapiro passed away in 2007 and in keeping with his personality he didn’t want a fuss, didn’t want a funeral or memorial, but his spirit lives on in his students and his gorgeous playing.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Wonderful article about one of our greatest and most beloved cellists. Dr david chew OBE

Did you mean to write Principal Cellist Frank Miller left the NBC Symphony to enlist? Frank Miller didn’t join the Chicago Symphony until 1959. He played for one season, and then came back from 1961-1985. He certainly didn’t leave the CSO to enlist in the military, since the war was long over by the time he joined. From what I understand, he played with the NBC Symphony from 1939-54, and was music director of the Orlando Symphony from 54-59. I know he was stationed at the Great Lakes Naval Base, sometime in the 40s I believe, but I didn’t think he was gone from the NBC Symphony for three years.

My recollection as a Shapiro alum is that Toscanini invited Shapiro to lead the NBC cello section when Miller enlisted, not Chicago.

Wouldn’t a better title for this feature be “Remembered Cellists”?

Thanks for the article Janet. Shapiro’s Nonesuch disc of Strauss and Shostakovich Sonatas is also great. He was born 1911, making him a contemporary of Andre Navarra and Tibor de Machula, whose Lalo recording Shapiro regarded highly.