Discovering Beethoven: A Visual Introduction

© mrtom-uk / Getty Images

Beethoven is well-known by all. However, to some this knowledge is often peripheral — just as one would not recognise an obscure Van Gogh when facing it, some average listener could struggle in identifying some of Beethoven’s works aside from Ta-Ta-Ta-Dah and Für Elise. But Beethoven is everywhere; especially in the visual world and film music. I personally made my way to classical music backwards — starting from the likes of Glass and Reich, towards Bach. As a result, it took me a little more time in my musical education to discover and get caught by Beethoven’s genius. But thanks to a couple of well-placed musical fragments, my introduction was shortcut and accelerated through my passion for the septième art.

Stanley Kubrick © i.redd.it

Starting with my first encounter: Kubrick is well-known for his strategic choice of music in his films, and one of his most famous use is of course the one of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in A Clockwork Orange. The composer’s Sturm und Drang — German for storm and drive — is here used to support the main character’s violence and irrationality. Alex, a young troubled Englishman takes pleasure in savagery and uses exhilarating music — the one of Beethoven — to support it. It is a direct denunciation of the Nazis who were misusing the composer’s music to support their propaganda and extermination of millions of people. As a piece of art, A Clockwork Orange would have not reached such heights if it was not for Beethoven’s dramatic music. That was my first conscious contact with the artist.

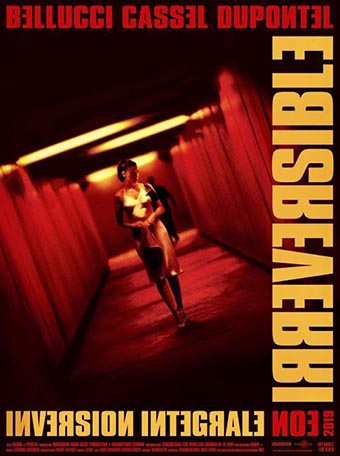

© www.kultcinema.ca

Later on, Irreversible, a fantastic yet disturbing movie by Noé — and direct reference to Kubrick’s works — employs reverse chronology to depict the revenge of a woman’s rape. If in A Clockwork Orange, the soundtrack is necessary to bring the dimension and psychology of the character to such levels, here Beethoven’s piece is used in a contrasting way, rather more discreetly and sporadically. While it is employed to emphasise violence in Kubrick’s movie, with the French filmmaker’s masterpiece this role is given to Bangalter — who is half of Daft Punk — and the Seventh Symphony here comes at the end to soothe the viewer and ease the tension of the plot, and bring peace and some sort of serenity. Now Beethoven had my attention.

© Wikimedia Commons

Van Sant’s Elephant denounces the recent shooting and massacres of America’s high schools. The film paints the portraits of several students — including the murderer — shortly before the shooting. While the psychological tension builds up as the film evolves, the music of Beethoven adds once more a daring contrast by how off it seems compared to its original context. The Moonlight Sonata and Für Elise’s delicacy and melancholy emphasise the dehumanisation and frustration of the main character — who repeatedly plays the music as he prepares his massacre —, as well as his turn to madness. To me, it felt refreshing to rediscover a music that I had heard so many times, without ever realising its actual full potential.

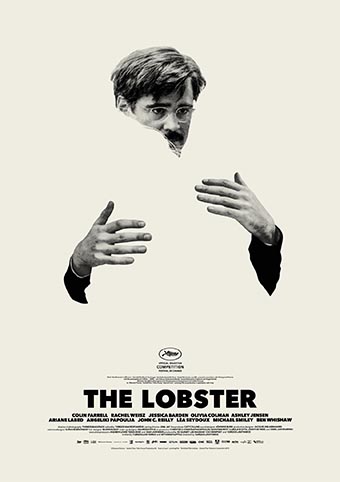

© alice.co.nz

Finally, the depiction of the Kafkaesque world of the Greek film director Lanthimos is stunningly emphasised by the choice of music for The Lobster. Described as being absurd, dystopian, black and comic — a signature trait from the director — the plot of the film gives forty-five days to its characters to find a romantic partner, before being turned into animals. Here, Beethoven’s First String Quartet adds to the absurd dimension of the film and participates in its irrationality and edginess. The pulsating opening drives the plot and hooks the listener from the first moments. In my opinion, the power of music in films resides in its capacity in transforming the images and bringing them up to another level. That is exactly what the music does in The Lobster.

Then I discovered the Grosse Fugue; and that what is. Beethoven had gotten into me. And, whether it is by emphasising, soothing, contrasting or adding absurdity, the use of Beethoven’s music in film marks the viewer; and it has been the case with me. Cinema has been my visual introduction to the German composer, and from here my Beethoven journey has grown and grown. It is a fragmented one; and I find the character of Beethoven to be marked by so much contrast and diversity that this approach makes sense to me. As a guiding principle, his Piano Sonatas act as a musical biography, depicting his evolution from a classical composer to musical genius. The German conductor Hans von Bülow even called them “The New Testament” of piano literature — Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier being “The Old Testament”.