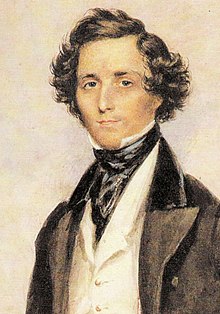

Felix Mendelssohn

How many composers can rightfully claim to have single-handedly invented a genre? Not that many, in fact, but Felix Mendelssohn would certainly be a strong candidate with his “Songs without Words.” Although Mendelssohn relied on an existing tradition of writing short lyrical pieces for the piano, the “wordless song” was entirely new. He first mentioned that term in an 1828 letter to his sister Fanny, explaining that “what the music I love expresses to me, is not thought too indefinite to put into words, but on the contrary, too definite.”

Mendelssohn’s Lieder ohne Worte

Novello in London published the first of eight volumes of “Lieder ohne Worte” in 1832, and for pianists of varying abilities and domestic music making, these publications were a bombshell. Hugely popular with a wide audience throughout Europe, the “Lieder ohne Worte” were also highly regarded by fellow composers who imitated the style and sometimes adopted his title for them as well.

Mendelssohn: Lieder ohne Worte (Songs without Words), Book 1, Op. 19b (Daniel Barenboim, piano)

Gabriel Fauré, 1864

The “Trois Romances sans paroles” by Gabriel Fauré probably date from 1863/64, but they had to wait almost twenty years before they were published in 1880 as his Opus 17. The title clearly references the “Lieder ohne Worte” by Mendelssohn, which had been translated as “Romance sans paroles” in the first French edition in the 1830s. These highly original and exquisitely crafted musical jewels seem to date from Fauré’s time at the Ecole Niedermeyer. It was Camille Saint-Saëns, who took charge of piano studies and recalled, “After allowing the lessons to run over, he would go to the piano and reveal to us those works of the masters Schumann, Mendelssohn, Liszt and Wagner from which the rigorous classical nature of our programme of study kept us at a distance.” Fauré’s gift for melody is amply apparent, while the accompaniment avoids any trace of virtuosity. Yet, these miniatures are exquisitely colored in translucent and unexpected harmonies that mimic not only Mendelssohn but also Schumann, a composer for whom

Fauré professed unswerving admiration.

Gabriel Fauré: 3 Romances sans paroles, Op. 17 (Nicolas Stavy, piano)

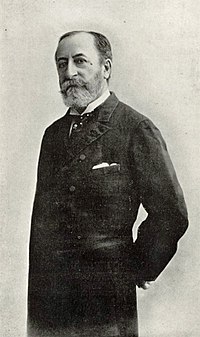

Camille Saint-Saëns

It might well have been the case of the student influencing the master, as Camille Saint-Saëns composed his single Romance sans paroles in 1871. The work was not actually published until 1903. Issued without opus number, the Lied melody appears in the middle register of the piano, accompanied by chords surrounding it in high and low registers. The gentle salon music character in this opening section is unmistakable, but Saint-Saëns clothes his sparse and lonely melody in a veil of increasing harmonic richness. In the central section, the key shifts to the major mode and Saint-Saëns ingeniously varies his musical language to produce wonderful inflections of color and sonority.

Camille Saint-Saëns: Romance sans paroles (Geoffrey Burleson, piano)

Every pianist in Paris seemed to have taken up the “Romance sans Paroles” genre. Charles Gounod published five of his transcribed mélodies and published them with this title.

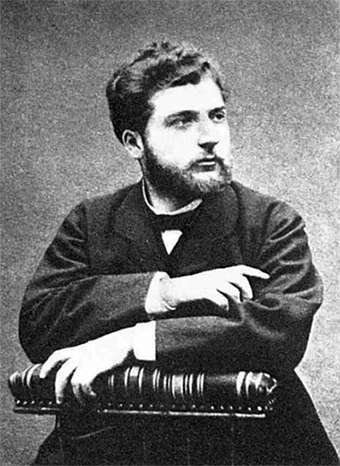

Georges Bizet

And when Tchaikovsky visited Paris, he observed, “you hear something new, sometimes very interesting, fresh, strong. Bizet is, of course, head and shoulders above them all. He is an artist who pays tribute to his century and the present, yet glows with genuine inspiration.” Bizet was an exceptional pianist, and an unbelievable sight-reader. A critic wrote in 1863, “his talents as a pianist is so great that no difficulty can stop him when sight-reading orchestral scores. After Liszt and Mendelssohn one could see few of his ability.” Bizet wrote relatively little for the piano as he enjoyed trying out a variety of different genres. The Chants du Rhin (Songs of the Rhine), subtitled “Lieder sans paroles” is a cycle of six dreamy miniatures. The set is symmetrically grouped around “La bohémienne” as the central piece, framed by two meditatively yearning pieces and two vividly exuberant ones, with “L’aurore” serving as an introduction.

Bizet: Chants du Rhin (Peter Vanhove, piano)

Great description on Bizet’s music, and other genius composers of the past.