Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Because of its brevity and seeming simplicity, the “Lied ohne Worte” became a musical and technical test bed for a good many aspiring composers. In addition, it could deliberately, or as was the case with Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, inadvertently express and communicate a level of intimacy that was never intended. The composer set out with his brother Anatoly on a long awaited holiday to Finland in 1867. But since they ran out of money, they called on their sister Sasha’s mother in law at Hapsal on the Estonian coast. And it was there, possibly encouraged by some unwilling flirtation, that Vera Davidova—the sister of Tchaikovsky’s brother in law—fell head over heals in love with the composer. The family feared the worst and was eager for him to depart, but Tchaikovsky attempted to reassure them. “It seems to me that if what you assume does in fact exist, then my absence is probably more harmful to her than my presence… when a woman who loves me confronts daily my far from poetic qualities, my untidiness, irritability, cowardice, pettiness, vanity, secretiveness, then the halo surround me when I am far distant vanishes very quickly.” Vera’s feelings, however, would only be strengthened by the dedication of three piano pieces Souvenir de Hapsal, with the set ending in the well-known “Chant sans paroles.”

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Souvenir de Hapsal, Op. 2 – No. 3 Chant sans paroles (Mami Shikimori, piano)

Louis Durey, 1930

Louis Durey (1888-1979) is certainly not a household name. But he briefly jumped into the limelight when his friendship with Francis Poulenc secured his part in a circle of young French composers known as “Les Six.” They briefly worked together under the auspices of their self-appointed spokesman Jean Cocteau to rebel against the excesses of late Romanticism in the works of Mahler and Schoenberg. The movement didn’t last very long, and since Durey absolutely hated the publicity hype, he quietly moved to the south of France in 1921. Durey had always been a rebel, creating the first piece of French twelve-tone music in 1914, and when he found the experience of serving in the army dehumanizing, he composed an opera based on a German play in protest. As he grew older, his political statements became more pronounced, and voicing his disgust with French involvement in Vietnam he set poems by Ho Chi Minh and Mao Zedong. And he brought the French “Romance sans paroles” into the 20th century.

Louis Durey: Romance sans paroles, Op. 21 (Francoise Petit, piano)

Louis Lefébure-Wély

Louis Lefébure-Wély (1817-1869) was a child prodigy who began his studies of music at the age of 4. Admitted to the Paris Conservatoire in 1832, he studied organ and piano and in due course became titular organist at the church of Saint-Sulpice in 1863—arguably the most coveted organist position in all of Europe. In addition, by joining forces with the famed organ builder Cavaillé-Coll, he also played a substantial role in the development of French symphonic organ music. Given such pedigree and curiosity it might not come as a surprise that Lefébure-Wély freed the “Lied ohne Worte” from its habitual piano medium and led it into the world of the symphonic organ. His Romance sans paroles is subtitled “Le chant de cygne.” It references a metaphorical proverb from ancient Greek mythology that the swan, having been silent for most of its life, sings a beautiful song just before death.

Louis Lefébure-Wély: Romance sans paroles, Op. 190 “Le chant de cygne” (Christian Ott, organ)

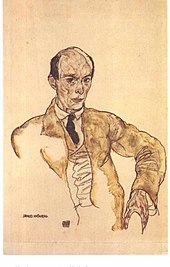

Portrait of Arnold Schoenberg by Egon Schiele, 1917

Scored for clarinet, bass clarinet, mandolin, guitar, violin, viola, violoncello, and low voice, the Serenade Op. 24 by Arnold Schoenberg is one of the most historically significant musical works of the early 1920s. It was written during a time when the composer, after years of experimentation, attempted to bring a sense of order to a bewildering proliferation of stylistic innovations. That sense of order became known as “twelve-tone” music, and the earliest clear examples of this technique appear in works composed around the time of the Serenade. Schoenberg was acutely in tune with the legacy of his musical inheritance, but he accorded music a level of expressive freedom that it would never again relinquish. The “Song without Words” is the shortest and simplest movement in the Serenade. It is scored as a customary three-part adagio song with simple and intimate cantabile qualities.

Arnold Schoenberg: Serenade, Op. 24 – VI. Song Without Words (Guy Deplus, clarinet; Louis Montaigne, bass clarinet; Luben Yordanoff, violin; Serge Collot, viola; Jean Huchot, cello; Paul Stingl, guitar; Paul Grund, mandolin; Louis Jacques Rondeleux, bass; Pierre Boulez, cond.)