© s3-eu-west-2.amazonaws.com

For any music journalist, to nail down an interview with Long Yu would be mission impossible. Not only because the man has an endless line-up of meetings, auditions to attend, rehearsals, concerts to lead who spends his day by minute, but also because he is known to shun the press. “Sometimes a journalist came and asked me to tell what I do and who I am. Do I have to explain every time how human evolved from apes?” is his signature rhetoric to any unprepared young reporter. But he too tries to evade journalists excessively prepared. It literally took me almost a year to finally secure an appointment with him.

© hkphil.org

In early May I was summoned by the unequivocal grand master to Shanghai Symphony Orchestra located in a lovely former French quarter, and offered the rare treat to listen to the first rehearsal by Charles Dutoit with the orchestra for two concerts with Martha Argerich in her Shanghai debut. Tickets to the concerts, sold out half a year ago, instantly become the most sought-after commodity in town even resold by scalpers at triple the price. As I met Long at the stage door after the first session was over, I implied that the choice of the programme by Charles Dutoit, Richard Strauss Don Juan and Otto Nicolai Overture to The Merry Wives of Windsor, is more of a biographical statement if not a blunt personal protest of the #metoo campaign’s seemingly conspiratorial consequences. “Exactly” was Long Yu’s reply in excitement. He then invited me into his mini van and off we went as scheduled.

Lin Daye

© http://www.shcmusic.edu.cn

We were on our way to the Pudong International Airport. It was a one hour ride to the airport, quiet, comfortable and undisturbed, precisely as I asked for. There Long Yu would catch his flight to Hong Kong for a meeting with Benedikt Fohr, the new chief executive of Hong Kong Philharmonic, and Jaap van Zweden, its music director shortly before the new season announcement. As HK Phil’s principal guest conductor since 2015, Long plays an instrumental role in introducing HK Phil at the Beijing Music Festival to the wider mainland audience, and getting Jaap concert engagements from Shanghai and Guangzhou, in continuing the official partnership with New York Philharmonic in Shanghai where Jaap is the music director.

Xia Xiaotang

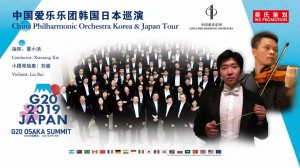

If the musicians’ world is a game subject to a set of hidden protocols governing the music industry like a Law of Nature, Long Yu must be its top predator thanks to his powerful friends. Untamed, he rules with pride his three orchestras, namely China Philharmonic, Shanghai Symphony and Guangzhou Symphony Orchestra and chairs the two festivals, namely Beijing Music Festival and Music in the Summer Air. He too looks after his pride, getting them food, finding them opportunities and trains them to be a qualified player like himself.

Jing Huan

© www.operamusica.com

At least a quintet of gifted young conductors benefit from Long’s guidance and connections in their career making. Yang Yang (楊洋), the most senior of them all, is the founding artistic director of Hangzhou Philharmonic and music director of China National Opera. Xia Xiaotang (夏小湯), probably the most loyal one, takes care of the youth orchestra and is chief conductor of China Philharmonic. Lin Daye (林大葉), an award-winning protégé, chairs both Shenzhen Symphony and the mighty conducting department of Shanghai Conservatory of Music. Huang Yi (黄屹), a Berlin trained disciple, heads the orchestras of Kunming and China National Ballet. Jing Huan (景煥), the only female of them, is the de facto chief conductor of Guangzhou Symphony. Together they have created unrivalled social bonding and an unbreakable group, dubbed as the Long Yu clique.

Huang Yi

© hkphil.org

Among the clique, the orchestras and conductors reach a delicate balance with shared interest. To any outsiders, collaborators, young artists, the clique acts as a conglomerate that offers lucrative return when it comes to visibility, concert engagement, tour opportunity, outreach programme, and career development. In any tough international negotiation, the clique forms Long’s strongest bargaining chip. Upcoming visits to Lucerne Festival and the BBC Proms of Shanghai Symphony Orchestra with Long Yu precede or succeed visits of Lucerne Festival Orchestra and BBC Symphony Orchestra to China. As the favor is reciprocated, cultural exchange is accomplished.

Ye Xiaogang: Twilight of the Himalayas, Op. 68

The Shanghai Symphony Orchestra with its conductor Long Yu at Deutsche Grammophon’s historic 120th-anniversary gala concert

© Schoierer/DG

The formation of a group of interest has brought unprecedented opportunities for composers also. Andy Akiho, John Corigliano, Chen Qigang (陳其鋼), Zhao Lin (趙麟), Ye Xiaogang (葉小綱), Zou Ye (鄒野) are among those who have received joint commissions. More living composers works are programmed, performed and featured by Long Yu in his enormous conducting engagements overseas or in his vast conducting repertoire, of which he has kept a low profile back home. Branded as COMPOSE 20:20, it is Long’s ambitious initiative to introduce 20 new works by Chinese composers to the West, and 20 new works by Western composers to China. He has already fulfilled the mission by now.

World premiere of Zhao Lin’s Duo, a SSO commission, with Yo-Yo Ma, Wu

Tong and Long Yu, November 13 2013

© Shanghai Symphony Orchestra

But the most important part of the clique is to form a collective that could potentially transform the orchestras landscape. For long Long is famed for his advocacy of professionalism in an orchestra’s infrastructure and administration, that is an orchestra run by people who understand the technical know-how, and run with disciplines that could uplift an orchestra to universally acceptable standards. In any public funded music institution, pursuing artistic value vigilantly can be sometimes translated to resistance to the party’s hardlines. In a country where cultural policy could be reinvented at any time, where black and white might be reversed overnight, having Long on the throne means consistency and sustainability. He leads to a temporary safe passageway in a galaxy of perpetual uncertain.

Conducting at MISA

© Shanghai Symphony Orchestra

In a way Shanghai Symphony is Long’s testing ground. Since he took the helm in 2008, the orchestra has undergone a series of fundamental artistic reforms, operating on the largest budget amongst its peers. From its own hall the orchestra holds annually a summer festival, an orchestra academy, a management symposium (on a rotating basis) plus a biennial violin competition giving out the highest prize money in its category. It’s the envy of the world.

Long Yu and Ye Xiaogang at the opening concert of Shanghai Spring Int’l Music Festival, April 28 2017

© Shanghai Symphony Orchestra

As we reached the airport, I finally mounted the courage to confront him on how he feels like being addressed as China’s Herbert von Karajan, a quote from a 2009 New York Times story by David Barboza who seized a Pulitzer in 2013 for reporting on the massive wealth of former Premier Wen Jiabao. “I feel embarrassed. That’s really embarrassing.” Long Yu quickly and jokingly dismissed.