Franz Joseph Haydn is considered the father of the symphony, and John Field (1782-1837), the father of the Nocturne. Although Field was born somewhere between Beethoven and Schubert, his music seems much closer to Chopin, who appeared thirty years later. As Majella Boland writes, “Field is credited for being the originator of the Nocturne and for the style of pianism regarded as Chopinesque. Although Field was not unique in composing in this style, his nocturnes secured a place in piano literature.”

John Field

The Field nocturnes are a window into the salons of 19th-century Europe. They define the personality of the composer and the environment of his time. As a Parisian critic writes, “Field follows no recognised system, he is of no school but a natural and original talent who sits quite simply at the piano, as if at his own fireside.”

Chopin heard Field play, and he taught the Second Concerto to his students. Field was a new pianist for a new era. As an artist he emerged from the spirit of Dussek and Clementi, but he pioneered the Romantic character piece. Glinka saw Field’s fingers falling on the keys like raindrops, “gliding like pearls on velvet,” into a world of dreams and allusions. Why don’t you join us for a sonic excursion into the 10 most beautiful nocturnes by John Field.

John Field: Nocturne No. 9 in E Minor, H. 46

In the Beginning

Born in Dublin in July 1782, John Field moved to London at an early age and was placed under the musical care of Muzio Clementi. The 12-year-old boy was an instant sensation, and Clementi took him on an extended tour of the continent. After performing in Paris and Vienna, teacher and student went on an excursion to Russia.

Louis Spohr met Field in St. Petersburg and spoke of “an awkward boy who knew no language except English and wore a single ill-fitting suit.” However, his playing enchanted Russian aristocracy, and “not to have heard Field play was a sin against art and good taste.” Field travelled between St. Petersburg and Moscow and acquired a number of wealthy students. And he composed what Robert Schumann called “divinely beautiful music.”

John Field: Nocturne No. 2 in C minor (Tyler Hay, piano)

St Petersburg Salon

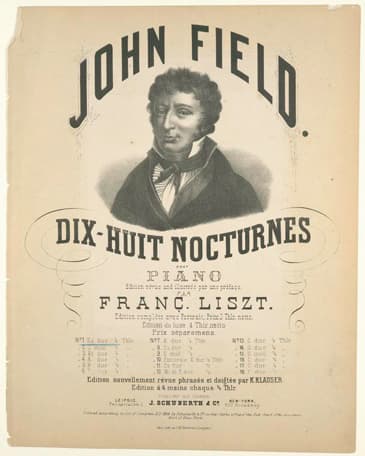

John Field’s Nocturnes, edited by Franz Liszt

The city of St Petersburg, also known as Petrograd, Petersburg and Leningrad, stood at the forefront of Russian musical culture. Established in 1703, the city flourished under Peter the Great, and the role of art and music assumed national significance. Not to be outdone, Catherine II made it compulsory for the aristocracy to attend musical and theatrical entertainments, and court musicians were required to compose operas, oratorios or concertos for state occasions.

The St Petersburg Philharmonic Society was founded in 1802, and it welcomed Franz Liszt, Clara and Robert Schumann, Hector Berlioz, Richard Wagner and Pauline Viardot. Wealthy patrons of the arts established their own instrumental ensembles, and the salon culture flourished. And the biggest name on the salon circuit was John Field, who mesmerised audiences with performances of his music. Field also set up a highly successful private piano studio, giving lessons to affluent and well-educated members of society.

John Field: Nocturne No. 11 in E-flat Major

Regional Song

Apparently, Field had a profound liking for regional song and dance, primarily of northern and western Russia. Katelyn Clark writes, “Field’s Russian empathy led him down sundry paths of lyric sentiment, ornament, rhythm, harmony and figuration.” The principal origin of the nocturne genre, to some scholars, is found in lengthy and swaying carriage journeys. After all, the 500-mile trip between St Petersburg and Moscow averaged more than a fortnight.

A contemporary writer relates, “The horses hurry me along. My coachman has launched into song, a mournful one, as usual. Anyone who knows the melodies of Russian folk songs will admit that they contain something that expresses spiritual anguish of the soul. Practically all the melodies of songs of this kind have a soft tone.” As Clark writes, “Field’s use of left hand ostinato emphasises a lack of fast harmonic progression… pervasively repeating, rolling broken chords against a loose, expressive melody. This might well evoke the perpetual movement of the carriage in counterpoint with the song of the coachman.”

John Field: Nocturne No. 7 in C Major (Roberte Mamou, piano)

The Pianist

John Field’s Nocturnes, Liszt’s edition

John Field was a special virtuoso, with contemporaries telling of his delicacy of touch and the refinement of his sonority. Powerful chords and blazing velocity were simply not part of his style. Instead, particularly in his character pieces, he focused entirely on tone colour and shading. As a pianist writes, “Field composed for his fingers…He preferred simpler forms which gave the impression of a free musical speech prompted by thought and emotion.”

In his short twilight meditations, namely the Nocturnes, words have faded away in favour of pure emotion. The melodic line is increasingly enriched with variations and ornaments, “which reflect the most imperceptible nuances of the soul.” However, the Nocturnes remain eminently pianistic. Field made great use of the technical improvements of the instrument, using a more sustained legato, greater variety of touch, subtler range of dynamics and a more efficient use of the sustaining pedal.

John Field: Nocturne No. 1 in E-flat Major

Nocturne

So, what is actually a Nocturne? Originally, the Italian term Notturno was frequently used in 18th-century music. It generally suggested a quiet and meditative piece associated with the night. The French form of the word “Nocturne” was not used until John Field applied it to some lyrical piano pieces written between 1812 and 1835. The first three were published in Leipzig in 1815, with two of them published earlier under the title “Romances.” This new genre now transferred the cantilena of Italian opera to the keyboard.

The Field scholar Christine Stevenson writes, “Nocturne, what a perfect name for a piece, coined in a language which was not his own by an Irishman transported from his native Dublin, catapulted into the French-speaking Russian aristocracy. Is there another musical title in the Romantic period which is so concisely evocative? A fancifully dark hue … A dream, which celebrates its round dances with longing, a longing which chose pain on its own, because it could not find again the joy that it loves.”

John Field: Nocturne No. 6 in F Major (Elizabeth Joy Roe, piano)

The Liszt Edition

In 1859, Franz Liszt published the first collected edition of Field Nocturnes. In all, he included 18 pieces; 16 Nocturnes thus titled by Field and 2 works associated with the same style but entitled “Romance,” and “Serenade.” As Liszt writes in the preface, “The charm which I have always found in these pieces, with their wealth of melody and refinement of harmony, goes back to the years of my earliest childhood.”

“Long before I ever dreamed of ever meeting their author, I was lapped, for hours, in dreams populated with forms that rose before my imagination while the music soothed me into a soft apathy like that caused by the fragrant fumes of rose tobacco full of jasmine perfume; hallucinations without fever, or rather floating evanescent images whose ravishing beauty, in a moment of delightful illusion, heightens emotion into passion.”

John Field: Nocturne No. 13 in D minor (Bart van Oort, piano)

Deep-seated Emotions

For Liszt, Field broke free of established species and introduced works in which “feeling and melody reigned alone, liberated from the fetters and encumbrances of a coercive form. To Field, we may trace the origin of those pieces, which were designed to paint individual and deep-seated emotions.” Some Field nocturnes are songlike in structure, with imagined vocal verses introduced and separated by accompaniment interludes.

Full of rubato, the Field nocturnes freely flow without a hint of thematic development. There is no actual narrative, but the implication of different moods, “allegories in sound touching on the dreamlike and indefinable, on fragilities of the self.” Liszt called them “genuine masterpieces of refined emotion, caressing as a moist and tender gaze… smoothly placid oscillations, half-sighs of the breezes, plaintive ailing, ecstatic moaning…”

John Field: Nocturne No. 18 in E Major, “Le Midi”

Impact

For Franz Liszt, the Field Nocturnes “opened the way for all the productions which have since appeared under the various titles of Songs without Words, Impromptus, Ballades, etc., and to him, we may trace the origin of pieces designed to portray subjective and profound emotion.”

Maurice Brown writes in the Groves Dictionary of Music, “Although the emotional range of most of Field’s nocturnes is not wide, and the phrase structure sometimes tediously predictable, the restrained elegance of his musical language and imaginative keyboard figuration made a great impression on subsequent Romantic composers, especially Chopin.” To be sure, the Nocturne became one of the most popular expressions for most pianist-composers of the time.

John Field: Nocturne No. 9 in E-flat Major (Gunther Hauer, piano)

Legacy

Contemporary listeners, familiar with the Nocturnes of both Field and Chopin, found Field’s subtler works superior. As one critic put it, “when Field smiles, Chopin makes a grinning grimace; where Field sighs, Chopin groans; where Field shrugs his shoulders, Chopin twists his whole body; where Field puts some seasoning into the food, Chopin empties a handful of cayenne pepper. In short, if one holds Field’s charming romances before a distorting, concave mirror so that every delicate impression becomes a coarse one, one gets Chopin’s work. We implore Mr Chopin to return to nature.”

The Field Nocturnes are a testament to his originality and vision. As a pianist writes, “Somehow these pieces give sonic shape to the nocturnal experience with its subconscious yearnings, amorphous fantasies, and primaeval remembrances. Here is a sort of universal music transcending the bounds of geography and time.”

One thing for sure, Field remains one of the most original figures in the development of Romantic piano music. I trust you enjoyed our musical excursion into the evocative world of the 10 most beautiful Nocturnes by John Field. Before we explore the Chopin Nocturnes in more detail, let us stay in Russia for a while. Please look out for a blog on the Nocturnes of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter