The Geneva International Music Competition is one of the world’s leading international music competitions, alternating between several main disciplines every year. Prizewinners include some of the world’s best artists, including Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli (piano), Pamela Bowden (voice), Heinz Holliger (oboe), and Tabea Zimmermann (viola), to name only a selected few. The 1957 competition, however, was special. In the piano category the sixteen-year old Martha Argerich was crowned the winner, but you might not know that she had to share the prize with Dominique Merlet.

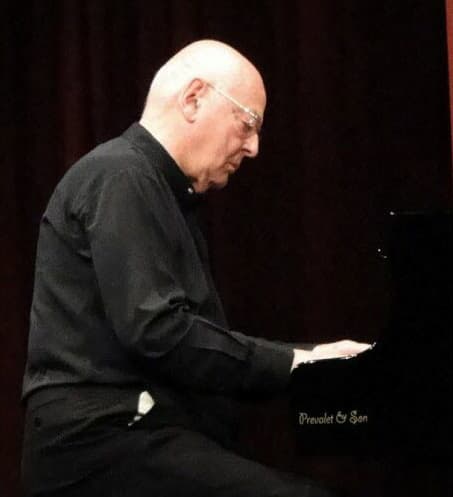

Dominique Merlet

Born on 18 February 1938 in Bordeaux, Merlet became a student of Roger-Ducasse, Louis Hiltbrand, and Nadia Boulanger. He won three first prizes at the Conservatoire de Paris before scoring his ex-aequo win in Geneva. Merlet embarked on an international career and made numerous highly acclaimed recordings. As a pedagogue Merlet worked in Paris and Geneva, and between 1956 and 1990 he was titular organist at Notre-Dame-des-Blancs-Manteaux in Paris. He is a regular member of the juries of the most prestigious international piano competitions, including the Chopin Competition in Warsaw.

Dominique Merlet Plays Chopin’s Berceuse in D-flat Major, Op. 57

Merlet’s Most Important Influences: Heinrich Neuhaus and Egon Petri

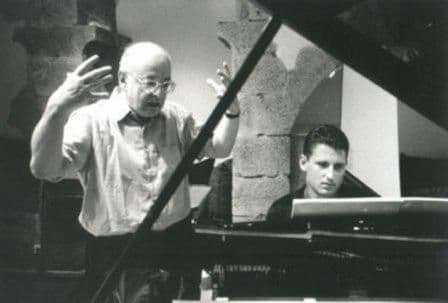

Dominique Merlet (4th from the left) at the Geneva International Music Competition, 1957

Merlet readily credits his teachers for his rapid and thorough development, and he counts the recordings of Egon Petri and Heinrich Neuhaus among the most important influences in his musical life and career. He explains, “It is obvious that when you hear Neuhaus play Chopin, you learn a lot, the color is so special. For me, Neuhaus is the greatest performer of Chopin’s music, because there is this simplicity, this great naturalness, this natural rubato; there are very few people who can play Chopin well.”

During his studies in Geneva, Merlet took lessons with Louis Hiltbrand, and he credits him with teaching a culture of touch, “in particular the qualities of legato, relaxation, and the beauty of sound.” Merlet also credits Pierre Kostanov with teaching him the technique of hand rotation. Both aspects have greatly influenced Merlet’s performances, and he has passed on his knowledge to many young artists who are now pursuing international careers, including Dana Ciocarlie, Jean-Marc Luisada, Philippe Cassard, Frédéric Aguessy, Xu Zhong, François-Frédéric Guy, Kotaro Fukuma, and Ha-Young Sul.

Jean-Pierre Leguay: Azur (Dominique Merlet, piano)

Merlet’s Thoughts on Piano Playing

For Merlet, the most important aspect of communicating music is achieved by an infinite variety of approaches to the keyboard. “Touch is the way to tame the instrument and to draw from it, if possible, a kaleidoscope of colors. I often tell my students, when they present a recital with music by three or four different composers, to give the impression that they are playing three or four different instruments.” For Merlet, touch is both a gesture and a feeling. “It all starts with a specific sonic imagination, in the head, and in the ear. There are pianists who play everything with the same gestures, the very same sounds, and it’s not very interesting.” Since pianists don’t have to be concerned with intonation, they have to be doubly vigilant when it comes to tone production. “An undemanding pianist may be satisfied with playing all the notes correctly. I currently fight with a student,” Merlet explains, “who plays with a high degree of virtuosity, but I have the impression that he doesn’t hear the sound coming out of the piano. It’s very ugly.”

Johannes Brahms: 4 Ballades, Op. 10 (Dominique Merlet, piano)

“Everything starts with the ear”

For Merlet, the link between an idiomatic touch on the piano is intimately connected to the personality of the pianist. “It is personality and imagination that leads to a sonic universe, and I think the older an artist gets the more personal their playing becomes… And hearing has to come first. Everything starts with the ear, and one cannot have a good technique if it does not start from the ear, even in scales and arpeggios. For me, the ear controls and anticipates the intentions of the pianist.” Sadly, as Merlet explains, there are also many listeners who cannot hear “all the subtleties. I don’t think the general public can say why they prefer to hear Radu Lupu rather than Kissin, and yet there is a gap between these two pianists.”

Merlet abhors the idea of motionless pianists playing the keyboard like a typewriter. As he explains, “there are pianists who are very pleasant to watch and others who are not at all. And then there are some that are not unpleasant to hear, but it is better to close your eyes.” Beautiful gestures give rise to beautiful sounds, “and such gestures are always circular, never vertical. There has to be a harmony between the gesture in relation to the keyboard, and the attitude of the body on the seat.” Merlet, for example, considers “Richter a tortured performer, always too close to the keyboard and constantly moving his back.” As he explains, “the position of the body is of utmost importance because everything works harmoniously and easily, and the impulses come naturally.”For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Watch Dominique Merlet Plays Ravel’s Miroirs, “Noctuelles” here.