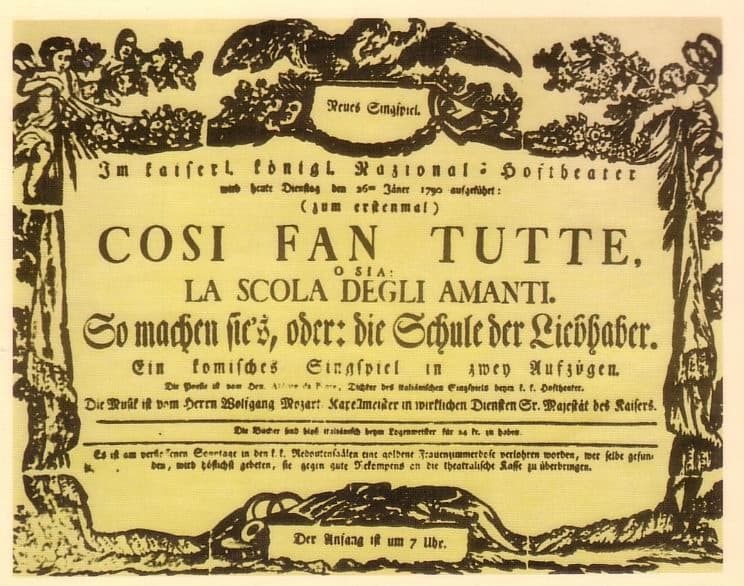

Ever since Mozart’s Così fan tutte: La scuola degli amanti premiered on 26 January 1790 at the Burgtheater in Vienna, Austria, its critical reception has been marked by ambivalence. For one, it opened during the Austro-Turkish War of 1787-91, playing on political tensions and with a plot that focused on military service.

Public Reception

Portrait of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart by Johann Georg Edlinger

As a scholar writes, “Perhaps it was simply, in all respects, too current and too real for the first audiences to recognize its deeper insights. And a contemporary opera that played on these fears, during a war that seemed a repudiation of Enlightenment political reforms, was not likely to win a wide following in that environment.” In addition, the opera was given only five times, before all entertainment was stopped by the death of Emperor Joseph II, and Così was not again performed in Vienna during Mozart’s lifetime. Much of the criticism focused on the libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte, and even Constanze Mozart suggested, “that the libretto was not up to her husband’s high standards.”

Mozart: Così fan tutte, “Sento, oh Dio, che questo piede”

Criticisms

A production of Mozart’s Così fan tutte by Glyndebourne

Even Antonio Salieri, for whom the libretto was originally intended, rejected the script. Mind you, he was still angered that Mozart was eventually given the commission. Widely considered inferior in quality to Mozart’s music, Johann Wolfgang Goethe became one of its most outspoken critics. He writes, “To be sure the over-simplicity of its subject, the weak delineation of the characters on the part of the poet, the situations lack of truth, the feebleness of the denouement, and above all the pitiful translations have contributed much to this judgment. All the greater than were the difficulties with which the composer had to battle.”

First performance of Così fan tutte

For Goethe, it was the quality of Mozart’s music, the glorious ensembles and heartfelt arias that saved the entire opera, but only barely. Goethe explains, “First one is struck by how delicately this opera is scored; how Mozart refrained from the sort of overburdening for which he has otherwise been criticized; how appropriately he has used the wind instruments. Add to that the harmony of the whole and the grace in the individual paintings, with what tenderness every emotion is handled; the truth of expression!”

Mozart: Così fan tutte, “Donne mie, la fate a tanti”

Synopsis

A production of Mozart’s Così fan tutte by the MET

To be sure, the plot is a philosophical fable about love, and bittersweet meditation on women’s faithfulness against a backdrop of disguises, false goodbyes, and deceptions. The story takes place in the Bay of Naples in the 18th century and the cynical bachelor Don Alfonso provokes his young friends Ferrando and Guglielmo by impugning the constancy of their fiancées, sisters Dorabella and Fiordiligi. Don Alfonso proposes that they tell their fiancées that they are leaving for war, and then return dressed as Albanian soldiers ready to seduce them. Initially, Fiordiligi and Dorabella are outraged when their servant Despina introduces the two Albanians. The two sisters at first reject them virtuously but soon allow themselves to be seduced by these new suitors who, under a false identity, gradually become disillusioned as they see their mistresses betraying them. Don Alfonso is delighted that his theory has been proven, and when the deception is revealed, the two couples reunite despite it all, with no great illusion about their happiness. Beethoven thought the story immoral, and Richard Wagner believed that Mozart had wasted his talent on this flimsy and inconsequential opera plot.

Mozart: Così fan tutte, “Una donna a quindici anni”

The Opera Music Composition

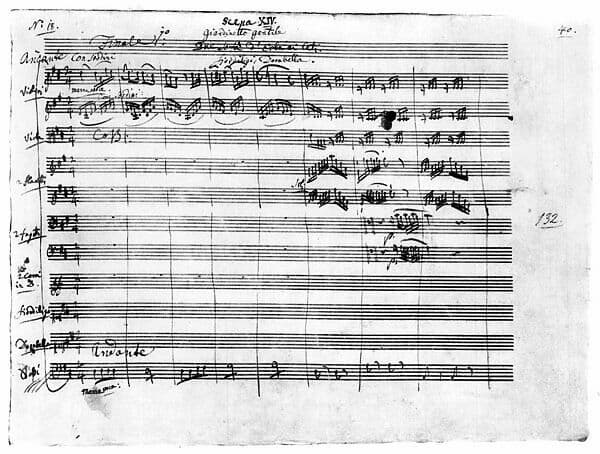

Manuscript of Mozart’s Così fan tutte

It has been suggested that in his music, Mozart “chooses to portray an extended and psychologically complicated interaction. This is not the way to show us that human nature is a mechanically predictable affair, a moral that, at first blush, seems to be central to the story of this opera. Instead, Mozart presents an intensely human dramatic situation, in which depth of character is pitted against a strong emotional force, namely love.” Generations of critics have seen Mozart’s Così as a transgression, a fall from the heights established by Le nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni. Yet, as Scott Burnham writes, “The music of Così is the sad ironic smile of one who has lost the Garden of Eden but learns the garden of beautiful apparition, one whom both participates and observes, believes and doubts, sympathizes and mocks. It is, I like to think, Mozart’s smile.” Mozart’s smile is actually confirmed by a funny anecdote. Mozart apparently severely disliked the prima donna Adriana Ferrarese del Ben, da Ponte’s arrogant mistress for whom the role of “Fiordiligi” had been created. “Knowing her idiosyncratic tendency to drop her chin on low notes and throw back her head on high ones, Mozart filled her showpiece aria “Come scoglio” with constant leaps from low to high and high to low in order to make Ferrarese’s head “bob like a chicken.” Now that is musical insight and funny to boot!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Mozart: Così fan tutte, “Come Scoglio”

The plot summary forgot to mention that when both couples are made up again between the two sisters and the “Albanians” each of the men takes the former fiancee of the other one… Still, it would be a mistake to judge at “level one” that is, all women are b…, but rather, that in those times women HAD to be in a relationship with a man – they couldn’t be bachelors like Don Alfonso – therefote the two sisters, fearing that their Italian fiances may be dead, prefer to “opt for safety” and be engaged to the Albanians… This said, the music is a masterpiece.

For Mozart, considering his Marianismo (for deep Catholics, the Virgin Mary is more important, more central, more beloved than the male with the two sides —the bad cop the Father & the good cop the Son—)* this opera is unique. Women are like the rest of the world: weak, fragile, prompt to fall into unfaithfulness, human. If you study Mozart’s Opus, females are always much better than men, from Susanna and the Contessa to Constanze and Pamina. Listen to the Ave Verum Corpus (K618) and then to the Requiem (K626). The first is assured, graceful, blessed; the second contorted, fearful, savage, anxious and…, incomplete, like the Great Mass (K427). According to Scott Burnham (Mozart’s Grace, Princeton University Press, 2013), the best Mozart Trio is from Così, ‘Soave sia il vento’. As Burnham says, the music here is so graceful and serious that we are not listening to a farewell between lovers, but to a farewell to Innocence.

* ‘Stevens defines Marianismo as “the cult of female spiritual superiority, which teaches that women are semidivine, morally superior to and spiritually stronger than men.” She explains the characteristics of machismo: “exaggerated aggressiveness in intransigence in male-to-male interpersonal relationships and arrogance and sexual aggression in male-to-female relationships.” Stevens argues that marianismo and machismo are complements, and that one cannot exist without the other.’ (Wikipedia, Marianismo.) In Mozart, Marianismo exists without machismo, let us note.