Victor Hugo published his Les chants du crépuscule on 25 October 1835, as the second of four volumes commonly referred to as the July Monarchy collections. “Twilight Songs” includes a short preface, a prelude poem, and thirty-nine additional pieces. “If the title suggests doubt, anxiety, and misgivings on the personal, religious, and political levels, the series of poems dedicated to Juliette Drouet suggest a hope found in a new day.” While the preface is filled with perplexity and doubt, the collection itself explores a substantial number of themes. Thematically it contains “political poems, rhymes on the Napoleonic cult, patriotism, the rich and the poor, materialism, poetry and art, nature, God and the religious questions, Juliette Drouet, and Madame Hugo.”

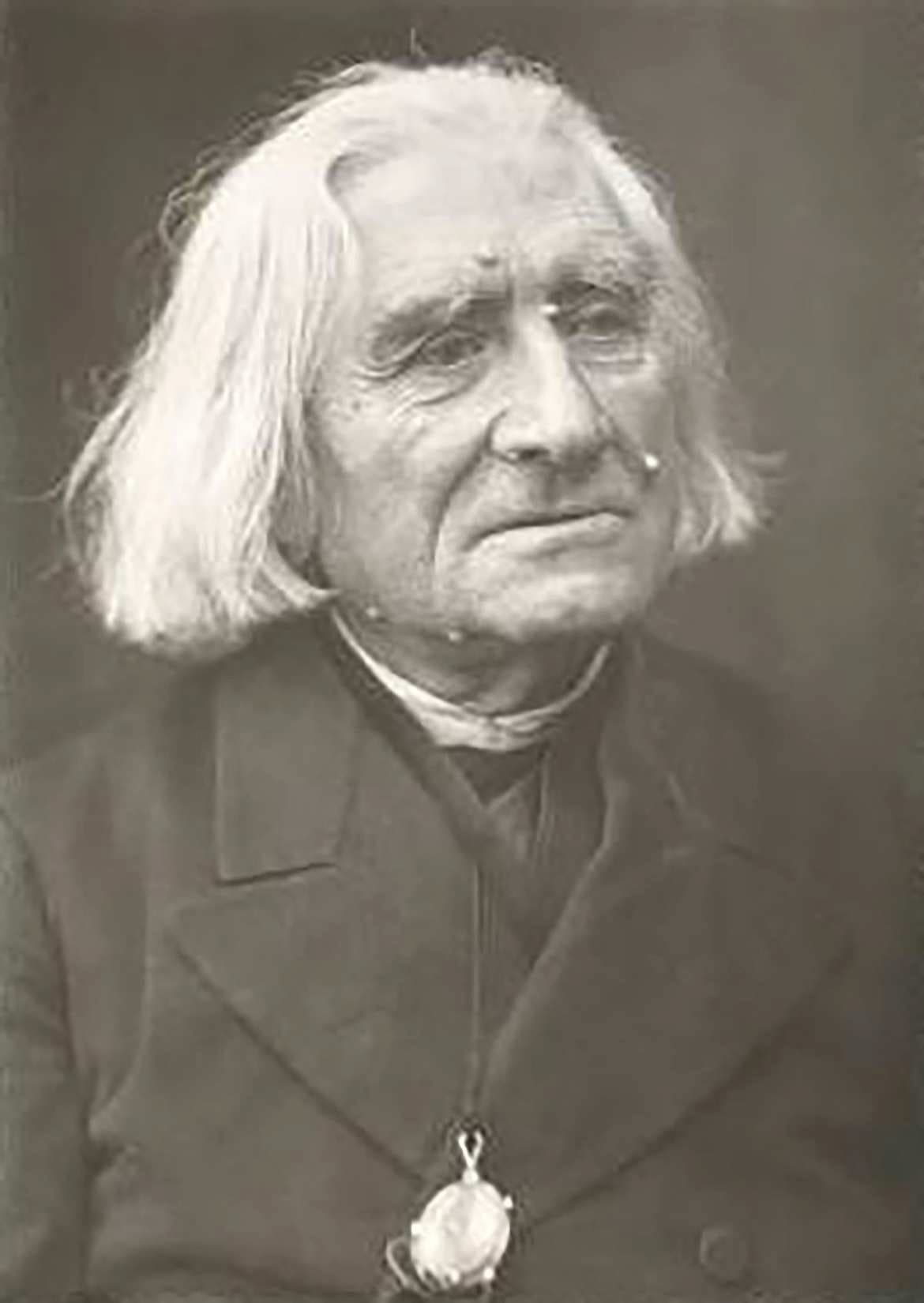

Franz Liszt at the age of 12

The twenty-second poem in the collection was originally titled “S’il est un charmant gazon,” put in the published version that appears under the title “Nouvelle chanson sur un vieil air.” Literary scholars have suggested that the poet might simply have “fitted new words to a tune he already knew.” In the event, the poem was most decidedly written for his mistress Juliette Drouet.

S’il est un charmant gazon

Que le ciel arrose,

Où brille en toute saison

Quelque fleur éclose,

Où l’on cueille à pleine main

Lys, chèvre-feuille et jasmin,

J’en veux faire le chemin

Où ton pied se pose!

S’il est un rêve d’amour,

Parfumé de rose,

Où l’on trouve chaque jour

Quelque douce chose,

Un rêve que Dieu bénit,

Où l’âme à l’âme s’unit,

Oh! J’en veux faire le nid

Où ton cœur se pose!

If there is a charming grassy knoll

Watered by the sky

Where in every season

Some flower blossoms,

Where one can freely gather

Lily, honeysuckle, and jasmine,

I want to make it the path

On which you place your feet.

If there is a dream of love,

Scented with roses,

Where one finds every day

Something gentle and sweet,

A dream blessed by God

A dream that God blesses,

Where soul to soul unites,

Oh! I want to make it the nest

In which you rest your heart.

Franz Liszt: “S’il est un charmant gazon” (1st version) (Nicolai Gedda, tenor; Lars Roos, piano)

In his initial setting of 1844, Franz Liszt only sets the first and last verses from this poem, omitting the following second stanza.

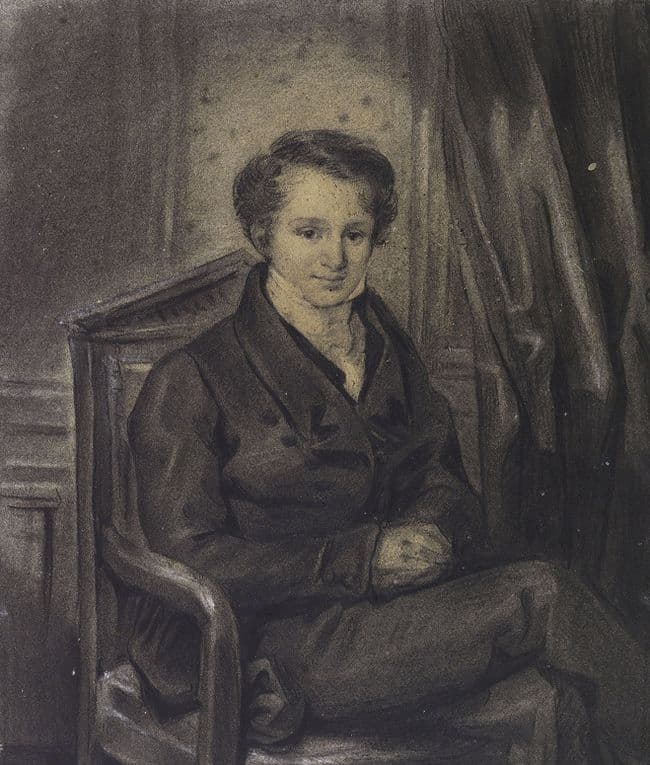

Victor Hugo

S’il est un sein bien aimant

Dont l’honneur dispose,

Dont le ferme dévouement

N’ait rien de morose,

Si toujours ce noble sein

Bat pour un digne dessein,

J’en veux faire le coussin

Où ton front se pose!

If there is a loving breast

Where honor rules,

Where tender devotion

Is free from all gloominess,

If this noble breast always

Beats for a worthy aim…

I want to make it the pillow

On which you lay your head.

A number of composers, among them Gabriel Fauré, had been attracted to the passionate verses of Hugo’s love poem. Liszt, in turn, initially produced a setting, which he revised roughly 20 years later. In a letter to the Austrian composer Josef Dessauer, Liszt stated, “my earlier songs are mostly too ultra sentimental, and frequently too full in the accompaniment.” As his musical conception and stylistic taste changed over time, he revised them two or sometimes even three times. The Liszt student Felix Mottl asked advice from his teacher about writing his own songs, and Liszt “suggested simplifying them, particularly with regard to accompaniments and modulations.” Liszt retains the 6/8-meter in both versions, however, the initial setting is rhythmically much more complicated. According to a scholar, Liszt “creates an odd rhythmic feel by placing the tonic A-flat not on the usual strong beat but on the second or the fourth sixteenth note, causing frequent confusion for singers and pianists.” In the second version, the sixteenth notes in the piano accompaniment are completely removed, and Liszt also simplifies the vocal line, making corrections to the prosody. Both versions are harmonically similar, and the postlude only sounds with slight variations in harmony and melody.

Franz Liszt: “S’il est un charmant gazon” (2nd version) (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Daniel Barenboim, piano)

Caricature of Victor Hugo, Cover of La Lune 19 May 1867

In “Gastibelza” Victor Hugo “created one of the most magical ballads in the world. The eleven stanza poem is found in Hugo’s 1837 collection Les Rayons et les ombres under the title “A Guitare.” A good many critics consider this last volume of the July Monarchy Hugo’s best lyrical work before the exile. In all, it contains forty-four entries, and the preface is “within the tradition of Hugo’s dialectical argumentation. Among its many themes is the role of the poet as the defender of liberty, and the political role of the engaged poet. It also contains an argument on the nature of theatre, the novel, and poetry.” The spirit of man is essentially reduced to three elements, to know, to think, and to dream; everything is found therein. The poem “Gastibelza” was inspired by the poet’s stay in Guipuzcoa, in the Basque region of Spain. Supposedly, it is based on the soldier José Miguel Sagastibelza, a native of Navarre. In translation, the original name in the Basque language means, “black earth orchard.”

Gastibelza, l’homme à la carabine,

Chantait ainsi:

Quelqu’un a-t-il connu Doña Sabine?

Quelqu’un d’ici?

Dansez, chantez, villageois! La nuit gagne

Le mont Falou.

Le vent qui vient à travers la montagne

Me rendra fou!

Quelqu’un de vous a-t-il connu Sabine,

Ma señora?

Sa mère était la vieille Maugrabine

D’Antequera,

Qui chaque nuit criait dans la Tour Magne

Comme un hibou.

Le vent qui vient à travers la montagne

Me rendra fou!

Dansez! chantez! Des biens que l’heure envoie

Il faut user.

Elle était jeune et son œil plein de joie

Faisait penser.

À ce vieillard qu’un enfant accompagne

Jetez un sou.

Le vent qui vient à travers la montagne

Me rendra fou!

Dansez, chantez, villageois! La nuit gagne

Le mont Falou.

Sabine, un jour,

A tout vendu, sa beauté de colombe,

Et son amour!

Pour l’anneau d’or du comte de Saldagne,

Pour un bijou.

Le vent qui vient à travers la montagne

Me rendra fou!

Sur ce vieux banc souffrez que je m’appuie,

Car je suis las!

Avec ce comte elle s’est donc enfuie,

Enfuie, hélas!

Par le chemin qui va à travers la Serdagne,

Je ne sais où.

Le vent qui vient à travers la montagne

Me rendra fou!

Je la voyais passer de ma demeure,

Et c’était tout.

Mais à présent je m’ennuie à toute heure,

Plein de dégoût.

Rêveur oisif, l’âme dans la campagne,

La dague au clou.

Le vent qui vient à travers la montagne

Me rendra fou!

Gastibelza, the man with the carbine,

Sang:

Did anybody know Donna Sabine?

Anyone here?

Dance, sing, villagers! Night is falling

On Mount Falou.

And the wind coming down from the mountain

Is driving me mad!

Did anyone Sabine,

My mistress?

Her mother was old Maugrabine

From Antequerra,

Who’ screech every night

Like an owl.

And the wind coming down from the mountain

Is driving me mad!

Dance! Sing! Make the most

Of what the hours bring.

She was young and her eye, full of joy,

Made me think of these things.

Throw the old man with a child

A penny.

And the wind coming down from the mountain

Is driving me mad!

Dance, sing, villagers! Night is falling

On Mount Falou.

Sabine, one day,

Sold everything, her dove-like beauty,

And her love!

For the ring of gold of the Count of Saldagne,

For a piece of jewelry.

And the wind coming down from the mountain

Is driving me mad!

Here on this old bench allow me to rest,

Because I am tired!

With this Count she ran away!

Ran away, alas!

She took the road to the Serdagne,

I don’t know where.

And the wind coming down from the mountain

Is driving me mad!

I saw her pass by my place,

And that was all.

But now I worry all the time,

Full of disgust.

An idle dreamer, my spirit at war,

And my dagger beyond use.

And the wind coming down from the mountain

Is driving me mad!

Franz Liszt: “Gastibelza” (Matthew Rose, baritone; Iain Burnside, piano)

Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt selected the first three and three last stanzas from Hugo’s poem and assigned the song for bass voice. The music is full of rich evocations of Spain and its culture, and Liszt’s subtitle “Bolero,” assigns the bolero rhythm as the basis for the piano introduction and interludes. Communicating a sense of romantic disappointment, Liszt begins his setting with a long rhapsodic piano solo, and piano and voice parts are closely aligned throughout. It is, without doubt, one of the most demanding songs in the Liszt oeuvre. As a consequence, it is rarely performed in concert. According to a scholar, “the many octave tremolos and leaps in this extended song can be exhausting for the pianist. In addition, the tessitura is so wide that the vocalist also tires quickly, and the wildly jumping notes in the voice part seem almost impossible to sing.” Liszt might have had similar thoughts, as he reworked his setting for solo piano in October 1847. As we know, Liszt is perhaps one of the most prolific transcribers with more than half of his piano output consisting of transcriptions of works other than his own. Liszt produced two collections of “Books of Songs for Piano alone.” While the first book contains six piano solo pieces based on texts by Heinrich Heine, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Marchese Césare Boccella, Liszt turns his attention to his own settings of Victor Hugo in the second volume. The second book closes with Gastibelza, “perhaps the most pianistic and technically demanding piece of this set.” Scholars have conjectured that the piano transcriptions were composed right on the heels of the original art songs, “if not actually simultaneously.” Some of the piano pieces in his “Book of Songs” might well be transcriptions, “but Gastibelza may cause one to cast doubts whether or not this piece is in fact a transcription of the art song, especially since this piece resembles the style of his rhapsodies.” As such, it might be prudent to consider this work not merely a transcription, but a different version altogether.

Franz Liszt: “Gastibelza” (Version for solo piano) (Alexandre Dossin, piano)

Liszt’s setting of “Quand tu chantes, bercée” was essentially unknown until it was published as part of an article by István Kecskeméti in Magyar Zene (Hungarian music) and The Musical Times in 1974. The song was discovered in a used bookstore in London, and that score had “belonged to an amateur musician named Matilde Juva Brance.” It contains a dedication written and signed in Liszt’s own hand, “F. Liszt/Paris/28 Mai 1849.” However, upon further investigation it turned out that Liszt wasn’t even in Paris in 1849, and that the setting probably dates from 1842, the same year Liszt composed his other Hugo songs. The poem originates in Hugo’s play Marie Tudor from 1833. Set in London in 1553, it is essentially a work of fiction that focuses on Queen Mary I of England and her hot-headed Italian lover Fabiano Fabiani. Fabiani is scheming to discredit the orphaned Jane Talbot in order to prevent her from reclaiming the Talbot estate. However, once he seduces Jane, her commoner guarding and fiancé Gilbert, assists Fabiani’s enemies at court to discredit him with the Queen. Predictably, the Queen is not overjoyed that her lover has been caught dallying with another girl, a commoner no less, and she throws both Gilbert and Fabiani in the Tower of London. Having second thoughts, the Queen is trying to save Fabiani and Jane is trying to save Gilbert. In the end, Jane arranges for Fabiani to be executed and Gilbert to be spared. Liszt only set the first stanza of this sweetly erotic poem spoken by Fabiani. Imitating the cradling motion of a lullaby, the music gradually ascends to Love’s true and ultimate heavenly paradise. It is still unknown why Liszt never published this version, but as a scholar states, “Liszt’s songs to French texts are more valuable than his German settings, perhaps because the novelty of character in his music arose from the outset from fundamentally non-German roots.”

Quand tu chantes, bercée

Le soir entre mes bras,

Entends-tu ma pensée

Qui te répond tout bas?

Ton doux chant me rappelle

Les plus beaux de mes jours.

Chantez, ma belle,

Chantez toujours!

When you sing in the evening

Cradled in my arms,

Can you hear my thoughts

Softly answering you?

Your sweet song recalls to me

The happiest day I’ve known.

Sing, my beautiful one,

Sing forever!

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Liszt: “Quand tu chantes, bercée”