The National Portrait Gallery in London holds images of important and famous British people as drawings, painting, and photographs. We will be ignoring the single portraits of musicians, conductors, composers, and others with a life in music and will examine, instead, those portraits where music or musical instruments have a role.

We’ll open with The Music Party, a 1733 group portrait by Philip Mercier of the children of the royal family. Three of the four people are making music: Frederick Lewis, Prince of Wales (1707-1751) is playing the cello, the other three people in the picture are his older sisters, but their identities cannot be absolutely verified. It is thought, however, that the harpsichord player is the Princess Royal, Anne, age 24; Princess Caroline, age 20, is playing the mandolino; and Princes Amelia, age 22, is reading from Milton. The house in the background is in Kew. It is the Dutch House where the Princess Royal lived before her marriage to Prince William of Orange in 1734.

Philip Mercier: The Music Party, 1733 (National Portrait Gallery, London)

Princess Anne was noted for her prowess on the harpsichord, but the others’ musical skills are not really known. We can read some potential disagreements in this image: the Prince and the Princess Royal did not get along and, because of the problems of identifying the women, it may be that the woman reading Milton isn’t Amelia supporting her head on her hand, but rather Anne, covering up her ear from the sound of the others’ playing.

The Prince learned the bass viol in 1732-33 and that instrument may be what the painter wanted to show, rather than the cello shown here. A bass viol would have had C-holes, rather than the F-holes on this instrument. The lack of an endpin, as on a cello, and the support of the instrument on the lower leg, shows its viol connections. The cello has 4 strings, as shown here, where a viol would have five to seven strings. The Prince grips the bow as one would for a cello, rather than with the more common underhand grip. In an ensemble such as this, he would probably be playing the bass line of the harpsichord part, rather like a basso continuo player, and rather than an independent part.

Domenico Scarlatti: Mandolin Sonata in D Minor, K.90/L.106/P.9 – I. Grave (Ugo Orlandi, mandolin; Sergio Vartolo, harpsichord)

At first view, you might think that this family portrait is of the father playing on the harpsichord while the mother sings from a song sheet. However, this is a portrait of the Burkat Shudi family and we have to read this in a different way. If you look at the hands of the man at the harpsichord, you’ll note that only one hand is on the keys and the other hand is holding a tool. Burkat Shudi (1702-1773) was a harpsichord maker and the painter, Marcus Tuscher, has chosen to show him tuning an instrument, which is said to have been made for Frederick the Great of Prussia. Catherine Shudi is shown, not with a piece of sheet music, but rather with a copy of her father’s will. The family portrait was painted around 1742, shortly after the family inherited money from Catherine’s father. His two sons are shown in clothes reflecting their ages, six-year-old Joshua is in a blue dress coat and five-year-old Burkat is shown in red baby-clothes. The cat, under the table, keeps an eye on the food in baby Burka’s hand. The whole picture is one of taste and prosperity, from the elegant carved chairs, the elaborate lock on the door, the hint of family and landscape portraits on the wall, the fine quality of their clothing, and the silver dishes on the elegant side-table.

Marcus Tuscher: The Shudi Family Group, ca. 1742 (National Portrait Gallery, London)

Shudi settled in London in 1718 and made harpsichords. As the harpsichord declined in popularity and the piano grew, the company shifted instruments. The last harpsichord was made in 1793. After Shudi’s death, the firm was taken over by his son-in-aw, John Broadwood, and did business as John Broadwood and Sons. Haydn played a Broadwood when he visited London in 1781, Beethoven received a Broadwood in 1818, and Chopin played Broadwood pianos when he toured Britain. Broadwood pianos are still made today.

George Frideric Handel: Keyboard Suite No. 5 in E Major, HWV 430 – IV. Air and Variations, “Harmonious Blacksmith” (Alan Cuckston, harpsichord)

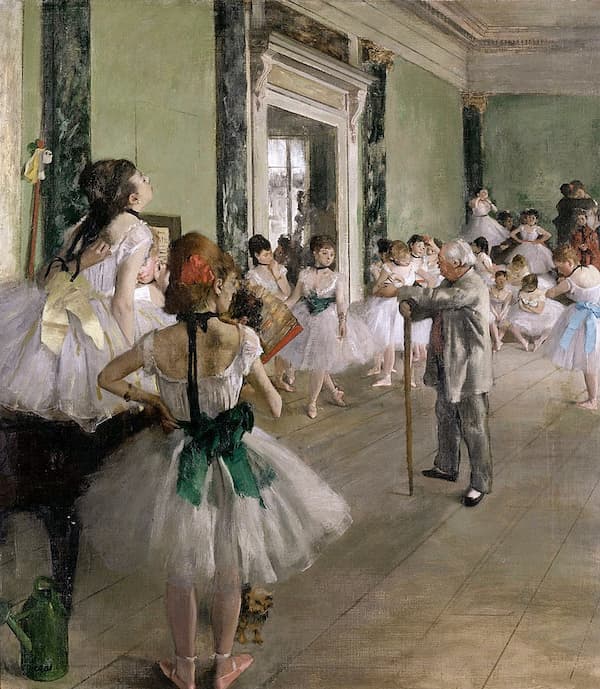

This 1779 group portrait shows an assemblage of 9 of Britain’s leading artistic and intellectual women, here shown in the guise of the 9 Muses. As the Muses were associated with Apollo, so these women are shown gathered around a statue of Apollo, shown holding his lyre.

Richard Samuel: Portraits in the Characters of the Muses in the Temple of Apollo, 1778

(National Portrait Gallery, London)

On the left we have the scholar and writer Elizabeth Carter (1717-1806) next to the poet and writer Anna Letitia Barbauld (1743-1825). In front of them, at her easel, is the painter Angelica Kauffmann (1741-1807). In the center is the singer and writer Elizabeth Ann Sheridan (1754-1792), shown holding a lyre. On the right, in front are the historian Catharine Macaulay (1731-1791), the writer and society leader Elizabeth Montagu (1718-1800), and the playwright and novelist Elizabeth Griffith (1727-1793). Behind the right group are the religious writer Hannah More (1745-1833) and the writer Charlotte Lennox (1720-1804).

The artists, Richard Samuel, constructed this group portrait as a speculation. The individual women did not sit for him, but rather he painted them from his own memory. The metaphor of the Muses was a powerful symbol at the time and by painting these professional women, all of whom except Elizabeth Montagu earned their livings through their work, Samuel was attempting to extend the metaphor of the arts.

Camille Saint-Saëns: Ascanio, Act III: Ballet: Divertissement No. 5: Apparition Phœbus, d’Apollon et les neuf Muses (Malmö Symphony Orchestra; Jun Märkl, cond.)

Charles Loraine Smith (of Enderby) made an etching of A Sunday Concert in 1782. Far from being a miscellaneous gathering, this was a very special gathering. Front and center, talking to the seated woman, we have the music historian Charles Burney (1726-1814), he was an organist in London and the first volume of his History of Music appeared in 1776, the next in 1782, and the final two volumes in 1789. Around the harpsichord we have, from the left, the musician Cariboldi on bass, the musician Hayford on an oboe, the composer and cellist James Cervetto, and, at the keyboard, the composer Ferdinando Bertoni. The singer Gaspare Pacchierotti holds a musical score in his hand, and next to him, is the musician Salpietro, At the end of the harpsichord are the composer Johann Christian Fischer on another double reed instrument and the musician Langani on a violin. The horn-player is unknown as is the man standing next to him.

Charles Loraine Smith (of Enderby): A Sunday Concert, 1782

(National Portrait Gallery, London)

The woman on the left is Lady Mary Duncan, married to Sir William Duncan, physician to King George III. She was noted for her very high wigs and for her infatuation for the singer Gaspare Pacchierotti, a mezz-soprano castrato and one of the most famous singers of his time. In this caricature, she seems not to be able to take her eyes off him. The woman Charles Burney is with is Polly Wilkes, about whom almost nothing is known.

Carlo Pallavicino: Vespasiano: Aria: È pur caro il poter dire (Filippo Mineccia, counter-tenor; Nereydas; Javier Ulises Illán, cond.)

In another royal portrait, we have a photograph of two sisters. Queen Alexandra (1844-1925), married to Edward VII, at the keyboard and her sister, the former Princess Dagmar of Denmark (1847-1928), known as Maris Feodorovna, Empress of Russia, married to Emperor Alexander III.

Southwell Brothers: Maria Feodorovna, Empress of Russia (Princess Dagmar); Queen Alexandra, 1863 (National Portrait Gallery, London)

This picture is a hand-coloured carte-de-visite (visiting card), which would have been given out to one’s friends and to visitors. They became popular in the 1860s and were eagerly collected. They went out of fashion with the availability of home photography in the early 20th century.

Queen Alexandra is shown at a small upright piano. However, this picture was taken in the photographers’ studio on Baker Street, Portman Square, so would have been a standard photographic background. It did give the sitters a way of showing their friendliness, though, as the younger sister turns the pages for her older sister.

The photographers, William and Edwin Southwell, set up their carte-de-visite business in 1862 and had a royal clientele. They went out of business in 1878 and their successor announced that all their negatives were going to be destroyed. The brothers’ work only survives in their extant carte-de-visites.

Edward Elgar: Queen Alexandra Memorial Ode, “So many true princesses who have gone” (arr. for chorus and orchestra) (Adrian Partington Singers; BBC National Orchestra of Wales; Richard Hickox, cond.)

In this political portrait of the first Labor Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, a family group is shown. The painting is of the Prime Minister’s estate at Chequers and shows the Prime Minister reading a newspaper, his son Malcolm leaning against a table, and his daughter Ishbel doing handwork. Playing on the floor are the older son Alister MacDonald’s children Jean and Bridget. At the back of the picture are the painter, Peggy Angus, with the family’s housekeeper at the piano.

Peggy Angus: Ramsay MacDonald with members of his family, 1930s

(National Portrait Gallery, London)

In this picture, we are shown the normalcy of life in the MacDonald household at the country house of the Prime Minister. The house was used to entertain foreign dignitaries or used as a country retreat for the prime minister from 1921 onward. In the post–WWI world, prime ministers were no longer guaranteed to be from a class that would have a country house, and so Chequers became a government property.

What we see is not the family making music but a member of the older generation, the housekeeper, as the pianist. In the 1930s, when this picture was painted, the drawing room piano was largely supplanted by the radio or the record player and so private music making left the home.

Albert William Ketèlbey: A Song of Summer (Rosemary Tuck, piano)

Musical instruments are used in these images to show culture (The Shudi family), the skills that royalty were thought to have (The Music Party and the carte-de-visite) and how music-making left the family in the 1930s. The art of music is more than the crafting of sound, it is also indicative of society and its attainments.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter