One of the great things to do in an art museum is to go through the collection to see what’s being pictured. This may sound a bit obvious, but for those with a musical bent, it’s an interesting exercise to see all the places that evidence of music turns up. It’s also interesting to think about why music was chosen to be shown in a painting.

In a collection as expansive as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, looking for music can take you everywhere around the world.

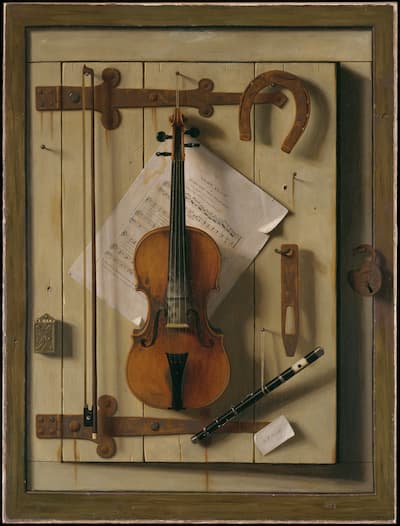

In William Michael Harnett’s Still Life–Violin and Music, we have a trompe l’oeil painting of a slightly open door that is hung with musical instruments. In the center, we have a well-used violin, with evidence of rosin at the bottom of the fingerboard and a bit of dirt where the instrument rarely gets touched. The bow to the left is well used as well, with yellowed horsehair, rather than the brilliant white you see everywhere today. The little piccolo, made of ebony and ivory, with silver fittings hangs at an angle below. The torn music sheet, a page from Moore’s Irish Melodies called “Saint Kevin or “By That Lake Whose Gloomy Shore” shows us that this was the fiddle of an Irish musician. Harnett has signed the painting in the bottom right corner on a name card stuck into the door joint. This two-dimensional picture is given life through the shadows and the utter reality in the painting.

Harnett: Still Life–Violin and Music, 1888 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Benjamin Britten: Folk Song Arrangements, Vol. 3, “British Isles” – No. 5. The Foggy, Foggy Dew (Peter Pears, tenor; Benjamin Britten, piano)

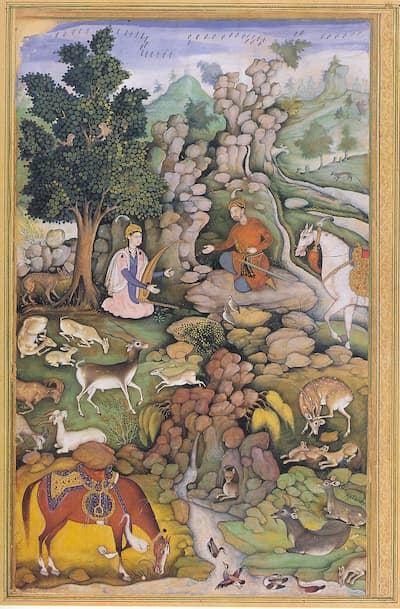

The Persian poet Nizami wrote his Khamsa in the late 15th century and it was answered a century later by the Indian poet Amir Khusrau Dihlavi. A copy of Dihlavi’s poems owned by the Mughal Emperor Akbar was illustrated, it is thought, by the artist Miskin. Here, the king, Brahram Gur, is shown with his slave Dilaram, whose music could make animals sleep or awaken. Around here, a herd of deer has succumbed to her song played on a harp-like instrument.

Miskin: Bahram Gur Sees a Herd of Deer Mesmerized by Dilaram’ s Music, from Dihlavi: Khamsa, 1597-98 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Marcel Tournier: Vers la source dans le bois (Towards the Fountain in the Wood) (Judy Lowman, harp)

Nicola da Urbino’s armorial plate tells the story of the contest between Apollo, on the left with his viola da braccio, and Pan, on the right with his pan pipes. This plate from ca. 1525 was commissioned by Eleonora Gonzaga, the Duchess of Urbino, as a gift for her mother, Isabella d’Este, the Marchioness of Mantua. The coats of arms are those of Isabella and her husband, Gianfrancesco Gonzaga. The imagery comes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, book 11. Midas was wandering his kingdom and came upon Pan, who he followed to Mount Tmolus. There, Pan was boasting about his musical prowess to his nymphs and decides to challenge Apollo to a contest, with the earth-god Tmolus as judge. Tmolus decides for Apollo. King Midas protests and Tmolus transforms his ears into donkey’s ears, shaming him forevermore. Here, Midas points to his favourite, Pan, while Tmolus is on Apollo’s side. Below the coast of arms in the centre, musical symbols have been used for decoration: the five-lined staff has symmetrical rest signs in the centre, a clef on the left and a double bar for ending on the right.

Nicola da Urbino: Armorial Plate with the Story of King Midas, ca. 1520-25

(Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Kamran Ince: Judgement of Midas – Act II Scene 4, “The Judgment” – Midas has the ears of an ass! (Matthew DiBattista, Midas; Philip Mark Horst, Apolla; Jennifer Goltz, Pan; Mikhail Svetlov, Tmolus; Abigail Fischer, Franny; Gregory Gerbrandt, Theo; Milwaukee Opera Theatre Chorus; Present Music Ensemble; Kamran Ince, cond.)

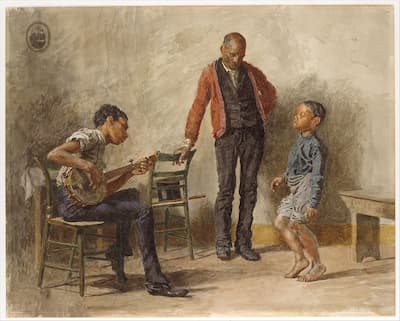

Thomas Eakins’ 1878 watercolour shows music being transmitted through the generations of the American black community. The father watches his grandson while an older child plays the banjo. On the wall behind the group is a very famous photograph taken by the Matthew Brady of Lincoln reading to his son Tad, taken in 1864. On the chair are a top hat and cane, emphasizing the casualness of the image we see. The banjo shows the typical 5-string design, with the outermost string held on a separate tuning knob on the side of the neck and the other four strings going to the top of the instrument.

Matthew Brady, Lincoln Reading to his Son Tad, 1864

Eakins: The Dancing Lesson, 1878 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

J.S. Bach: Violin Partita No. 3 in E Major, BWV 1006 – I. Prelude (Bela Fleck, banjo)

The French artists Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres rarely did group portraits, but in this 1818 drawing, he captured the 3 Kaunitz sisters, Leopoldine, Caroline, and Ferdinandine, daughters of the Austrian ambassador to Rome, Prince Wenzel von Kaunitz-Rietberg. The sisters, dressed in the height of early 19th century fashion, stand ready to perform. One, perhaps to sing, another to turn the pages, and the third at a square piano, with music ready. The sisters, age 13 to 17 in the picture, are emblematic of the cultured world that readily adopted women’s skills at music.

Ingres: The Kaunitz Sisters (Leopoldine, Caroline, and Ferdinandine), 1818

(Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Joseph Haydn: 6 Original Canzonettas – No. 1. The Mermaid’s Song, Hob.XXVIa:25 (Yukari Nonoshita, soprano; Kukuko Ogura, square piano)

The commedia dell’arte character Mezzetin, whose name means ‘half-measure’ in medieval Italian, is adept at scheming and making trouble. He’s musically talented and can sing and dance. He’s generally dressed in stripes and his colour is red or burgundy, where his brother Brighella’s colour is green. He always wears a tabaro, a short cape. In this painting by Antoine Watteau, the love-lorn Mezzetin sings and plays guitar to an unknown audience. It’s a measure of his lack of desirability that even the statue in the misty green garden behind him has turned her back on him. The guitar is thin-bodied in the 17th-century style, with the rosette filled with an internal design, as on this late 17th-century model.

Voboan (attributed to): Guitar, 1697 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Watteau: Mezzetin, ca. 1718-20 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Robert de Visée: Guitar Suite No. 9 in D minor – I. Prelude (Taro Takeuchi, guitar)

Starting in 1478, the designer Francesco di Giorgio Martini designed a study room, a studiolo, for the Ducal Palace in Gubbio. The walls are made of a variety of woods, chosen for the colours, and include walnut, beech, rosewood, oak, and fruitwoods. All the design is done in intaglio, with the different wood colours used to create the feeling of depth. The room is shown with the trompe l’oeil doors open, inviting the audience to explore what each space holds. Next to the front doorway, Panel 5 holds two stringed instruments and a portative organ. The lute, on top, also has two pipes lying on the shelf with it.

Panel 5 with 2 stringed instruments, 2 pipes, and a portative organ, ca. 1478-1482

(Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Panel 5, Detail, ca. 1478-1482 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In panel 8, there’s a harp and a tambourine.

Panel 8: cupboard with books, harp and tuning key, wooden ring with two rows of jingles, and brass candlestick, ca. 1478-1482 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In panel 9, there’s a mix of musical and measuring instruments: an upside-down cittern, dividers, an hourglass, a plumb bob and a set square.

Panel 9, Detail 2: upper section of cupboard, with dividers, cittern, sandglass, plumb bob and set square, ca. 1478-1482 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In the lower section of panel 10 are a pipe and tabor, which could be played by one performer. The box that looks like a tambourine is actually filled with candied fruits.

Panel 10: upper section, cupboard with tabor, pipe, box filled with candied fruits, dagger and book, ca. 1478-1482 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Panel 10, Detail, ca. 1478-1482 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The room is a tease for the eyes, urging the onlooker to reach out and use the tools presented so invitingly. Every possible field of study is here – from music to architecture, to dancing and fighting. And everywhere there are books. As a room to study in, it was probably an enormous distraction. As a room to appreciate the arts, it’s unmatched, except for the other one Martini created in the Ducal Palace in Urbino, now part of the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche.

Francesco Landini: Codex Faenza: Non avra ma’pieta questa mia donna (Ensemble Unicorn, Michael Posch, cond.)

There’s music everywhere in the museum – look for it as you walk through any museum and you’ll see how music can be used as indicative of culture and refinement, or, in the hands of Pan, as indicative of a less decorous life. It can show a depth to a person that a mere drawing can’t convey alone.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter