George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) composed some of the most memorable and famous melodies on this planet. He had an incredible gift for writing gorgeous melodies that “perhaps so strongly and clearly imply the harmony that it almost does not need to be realized.” In his operas, the human voice is the most important element, and Handel primarily relies on the A-B-A structure of the “da capo aria” in his operas and oratorios.

Georg Frideric Handel

In the reprise of the A section, the singer presents an improvised ornamented version of the melodic line specifically designed to show off the performer’s strengths. With the voice considered the most nuanced instrument, the “meaning of the text and the musical expression are closely aligned, with poetic language and musical dramatization accentuating each other.” It’s not surprising that the operas of Handel dominated the stages well into the 18th century, and they have certainly defined the “opera seria” genre. In a previous blog we listened to the wonderful music Handel composed for his operatic overtures, and today we will listen to 10 exciting operatic arias by Handel, in no particular order.

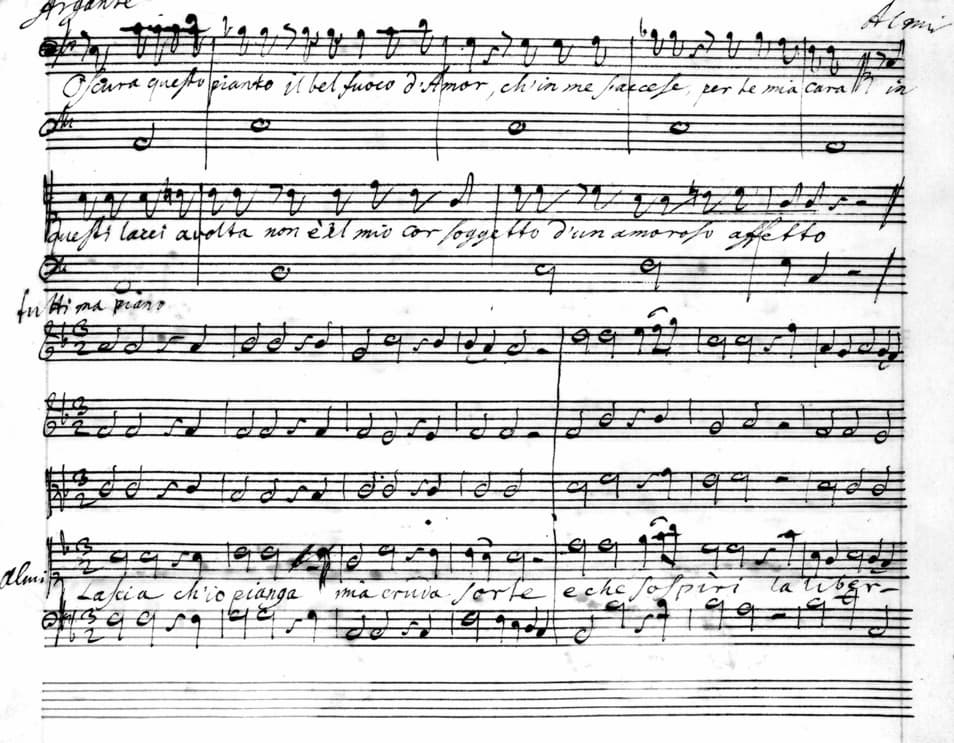

George Frideric Handel: Rinaldo “Lascia ch’io pianga”

At the top of my list, certainly in terms of popularity, we find the aria “Lascia ch’io pianga” (Let me weep) from the 1711 opera Rinaldo. The action takes place during the First Crusade, and Christian forces under Goffredo are laying siege to the city of Jerusalem. His brother Eustazio and his daughter Almirena, who loves the knight Rinaldo, accompany him. King Argante and his lover, the powerful sorceress Armida, Queen of Damascus, meanwhile defend the city of Jerusalem. As it happens, Almirena is captured by Argante, who is holding her prisoner. To make things even more complicated, Argante has just disclosed his passion for her, having fallen in love at first sight. “Lascia ch’io pianga” is a heartfelt plea for her liberty addressed to her abductor Argante.

George Frideric Handel: Rinaldo “Lascia ch’io pianga”

Let me weep over

my cruel fate,

and let me sigh

for liberty.

May sorrow shatter

these chains,

of my torments

out of pity alone.

The aria expresses the deeply sorrowful emotions of the heroine, and the simple and subdued accompaniment allows for exclusive focus on the vocal line. From a visual perspective, I very much like the featured Joyce DiDonato version, but the speed of the performance seems so very slow.

George Frideric Handel: Alcina, “Verdi prati”

“Verdi prati,” (Green meadows) from the opera Alcina is of central importance in the opera as the character Ruggerio is predicting of what is to come for Alcina and her magical island. The sorceress Alcina is a powerful character, and everything on the magical island is either an illusion or a former lover transformed into a tree, a rock, or something else. She is certainly fierce and shares the stage mainly with Ruggiero, who under her magic spell is her mortal husband and passionate lover. In his aria, Ruggerio is predicting her coming defeat and the ultimate vengeance.

George Frideric Handel: Alcina, “Verdi prati”

Green meadows, pleasant woods,

You will lose your beauty,

Pretty flowers, flowing waters,

your beauty will quickly change.

Green meadows, pleasant woods,

You will lose your beauty.

And when the beloved vision will fade,

everything will change

into the former horrible appearance.

As we can hear in Handel’s gorgeous music, Ruggerio has already figured out Alcina’s major weakness. She has in fact fallen in love with Ruggerio, and he is determined to eventually break her spirit and her heart in order to return to his wife and duties.

George Frideric Handel: Serse, “Ombra mai fù”

Initially, Serse was a complete failure but it has since become one of the most popular Handel operas, “as the lightly ironic and occasionally farcical tone readily resonates with stage directors and audiences alike.” The opera proper opens with a very short and strange love song sung by Xerxes to a tree. However, it inspired Handel to compose one of his best-loved melodies. In fact, “Ombra mai fù” has been arranged for all voice types, instruments, and ensembles under the title “Largo from Xerxes.”

Serse

Tender and beautiful fronds

of my beloved plane tree,

let Fate smile upon you.

May thunder, lightning, and storms

never disturb your dear peace,

nor may you by blowing winds be profaned.

Never was a shade

of any plant

dearer and more lovely,

or more sweet.

Serse abounds with mismatched lovers, plenty of quarreling, jealousy, and plenty of cross-dressing, and as the operatic narrative unfolds we quickly realize that Xerxes should have stuck with loving that tree.

George Frideric Handel: Agrippina, “Voi che udite il mio lamento”

George Frideric Handel: Agrippina, “Voi che udite il mio lamento” (Thierry Gregoire, counter-tenor; Grande Écurie et la Chambre du Roy; Jean-Claude Malgoire, cond.)

George Frideric Handel: Agrippina title page

In the aria “Voi che udite il mio lamento” (You who hear my lament) from Handel’s 1709 opera Agrippina we are gripped by a melody of “minor-key chromaticism and plentiful suspensions in a heartfelt plea.” According to scholars, “this is one particularly vivid example of the annexation of the tragic mode of expression by a male character.” In the opening recitative, Ottone is insecure and unhappy, and he expresses his misery. To heighten the drama, Handel added orchestral accompaniment, and time slows down in the famous aria. Handel also expands the first two lines of the text so that they fill the entire first section of the aria. On the surface it seems that the emotional volatility has passed, but “the aria instead pulls us further into Ottone’s psyche, expanding and defining his misery.”

You who hear my lament,

take pity on my suffering.

I lose a throne, which I despise,

but my treasure, whom I prize so greatly,

ah! to lose her is a cruel torture,

which discourages my heart.

George Frideric Handel: Giulio Cesare, “Va tacito e nascosto”

The da capo aria “Va tacito e nascosto” (Silently and stealthily) comes from the opera Giulio Cesare, and is sung by the title character. It was written for the alto castrato voice of the celebrated Senesino, and is scored for strings and natural horn. The use of the horn as a solo instrument is frequently cited, as it represents the dramatic themes of hunting and nobility. Essentially, Caesar compares himself to a stealthy hunter carefully tracking his prey.

George Frideric Handel: Giulio Cesare

How silently, how slyly,

When once the scent is taken,

the huntsman tracks the spoor.

The traitor shrewd and wily,

ne’er lets his prey awaken

unless the snare be sure.

During a 1784 performance, the music historian Charles Burney was in the audience and he writes, “Whoever is able to read a score, and knows the difficulty of writing in five real parts, must admire the resources which Handel has manifested in this. The horn part, which is almost a perpetual echo to the voice, has never been equaled in any air, so accompanied, that I remember.”

George Frideric Handel: Giulio Cesare, “Son nata a lagrimar”

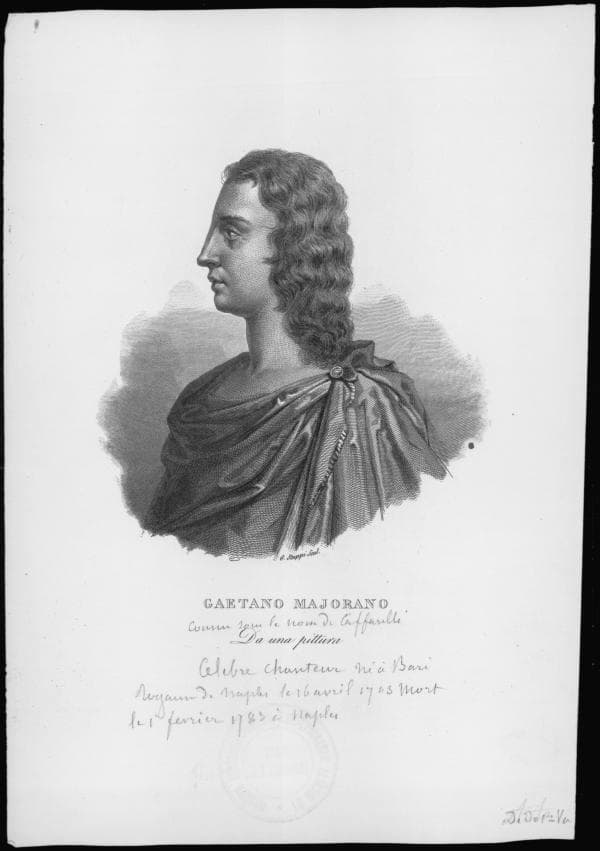

Shall we briefly talk about the undisputed rulers of the 18th century opera stage? I am talking about surgically altered boys, better known as castrati. As my colleague has written, “the taste for castrato voices arose mainly because in large parts of Italy, including the Vatican, women’s voices were not allowed in church.” About 4,000 boys a year were mutilated, and most of them never achieved fame. However, the few that did make it brought unknown riches to their impoverished parents, and thus the vicious cycle continued. The highest fees were paid in London, with Handel supremely reigning over the castrato craze in Italian opera.

Senesino

It was Handel who brought Francesco Bernardi aka Senesino to London, and he was a superstar with superb musical qualifications. He was renowned for “brilliant and taxing coloratura in heroic arias and expressive mezza voce in slow pieces.” Apparently, he had no equal in the pronunciation of recitative, and he “was unsurpassed in accompanied recitatives.” In all, Handel composed seventeen leading roles for Senesino, and the castrato sang in all 32 operas produced during this period. Since the castrato in opera is clearly a thing of the past, we will most likely hear their roles taken up by countertenors today, as in the featured duet from Giulio Cesare.

George Frideric Handel: Acis and Galathea, “O ruddier than the cherry”

Technically speaking, Acis and Galathea of 1718 is considered the pinnacle of pastoral opera in England. The English libretto was fashioned by John Gay of Beggar’s Opera fame, and it first sounded at the stately home of the Duke of Chandos, at Cannons. The story is derived from Roman mythology and the shepherd Acis is gently pursuing the nymph Galatea. The giant Polyphemus quickly puts an end to this idyllic setting of rural happiness. He is burning in his love of Galatea, and burning in his hate for Acis. When he sees the lovers pledging eternal faith to one another, he hurtles a rock at Acis, killing him instantly. Galatea mourns the loss of Acis, but she decides to use her divine power to make him immortal and transforms him into a fountain. “I rage, I melt, I burn,” Polyphemus sings in the recitative, and the charming aria “Ruddier than the cherry” is adorned with a happily tweeting piccolo line, that nevertheless, is unable to detract from his fundamental malevolence.

Atis and Galathea (Pompeo Batoni)

O ruddier than the cherry,

O sweeter than the berry,

O nymph more bright

Than moonshine night,

Like kidlings blithe and merry.

Ripe as the melting cluster,

No lily has such lustre;

Yet hard to tame

As raging flame,

And fierce as storms that bluster!

George Frideric Handel: Orlando, “Sorge infausta una procella”

Let’s stay for a moment with the bass voice, and Handel’s exceptional aria “Sorge infausta una procella” (Rough tempests arise) from Orlando. It is widely considered one of Handel’s greatest arias for the bass voice, and Charles Burney called it “Handel’s grandest style of writing for a bass voice.” It was written for the Italian bass Antonio Montagnana, brought to London by Handel. Montagnana would eventually jump ship and desert Handel for the rival Opera of the Nobility, but he was a widely acclaimed and remarkable singer. Apparently, he had a sizable voice that projected well into the opera house. According to one eyewitness who saw a performance of Orlando, Montagnana “sung…with the noise like a canon.” He is said to have had commanding power in the low tessitura and a vocal range of more than 2 octaves. And he was certainly praised for his “depth, power, mellowness and peculiar accuracy of intonation in hitting distant intervals.” “Sorge infausto” contains an abundance of coloratura passages, as the character Zoroastro rebukes Orlando for devoting himself to love instead of to glory.

George Frideric Handel: Orlando

Rough tempests arise

which obscure heaven and seas.

A brighter star does then impart its rays

and gladdens every heart.

The strong may often err,

but when they see their error,

What was once a source of woe,

then turns to joy.

George Frideric Handel: Teseo, “Morirò, ma vendicata”

George Frideric Handel: Teseo, “Morirò, ma vendicata” (Dominique Labelle, soprano; Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra; Nicholas McGegan, cond.)

The central character in Handel’s Teseo is the temperamental sorceress “Medea,” and Handel’s music shows him at his best, varying from lovelorn beauty “Dolce riposo” to venomous fury “Morirò, ma vendicata.”

Teseo: Soldier’s dance (The New York Baroque Dance Co.)

I shall die, but avenged,

avenged shall I die.

Before my death I shall see my rival cut down

and slain,

alongside the faithless man

who has cruelly insulted me.

In a number of Handel opera arias, the opening section of the da capo frequently contrasts overwhelming despair with a feisty display of resolve in part two. In “Morirò,” however,

Medea presents both despair and vengeance within the first line of the text. Controlled by her passions, the sorceress can’t even wait for the orchestra but immediately starts spouting her threats. Without doubt, this is one of my favorite Handel arias.

George Frideric Handel: Rodelinda, “Dove sei, amato bene”

When I first started to write this blog on Handel’s operatic arias, I was simply overwhelmed by the boundless riches offered by the composer. How would I finish this blog of 10 exciting operatic arias when I had literally hundreds to choose from? And then I read in a journal that Rodelinda is considered one of Handel’s greatest works.

Renée Fleming in Rodelinda

Charles Burney wrote, “it contains such a number of capital and pleasing airs, as entitles it to one of the first places among Handel’s dramatic productions.” And he particularly notes the aria for Bertarido in Act 1, “Dove sei, amato bene,” (Where are you, my dear-beloved) calling it “one of the finest pathetic airs that can be found in all his works… This air is rendered affecting by new and curious modulation, as well as by the general cast of the melody.” No matter if Handel is composing a soulful lament or a rage aria, he always captures the emotional essence of a particular character in music. I would say, he is one of the greatest opera composers of all time.

Where are you, my dear-beloved!

Come and console my soul!

I am overcome with torments

and my painful laments

I can release with you only.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

That Handel is not recognized as one of the great composers of opera is puzzling. Perhaps his Messiah led people to regard him as just another Bach, writing for the church. But Handel, though by birth German, became an Italian composer after his studies in Rome, where he worked alongside Corelli and Vivaldi. Thank you for these selections. As for my favorite operas, I would definitely list Agrippina, and also Theodora, a concert on stage, which apparently Handel considered his greatest work. Today we have these truly astounding singers…Jaroussky, di Donato, Bartoli (fingers crossed she will be around for a long time), and two fine French singers, Stutzmann and Labelle. And let’s always thank the ancient music groups and musicians in Great Britain as well as William Christie for reviving Handel and his contemporaries. (PS: another great American singer of baroque music are Amanda Forsyth and Danielle di Niece).