George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) must be one of my all-time favorite composers. But I am a little shy to tell you that I only know a very small part of his music. When I checked a musical dictionary I found that he composed “42 operas, 29 oratorios, well over 120 cantatas, trios, and duets, countless arias, chamber music, keyboard works, a substantial number of ecumenical pieces, odes and serenatas, and 16 organ concerti.” Wow, that’s a lot of music! And for 36 years of his life, Italian opera was his major preoccupation. Handel was not a revolutionary working in this genre, but what sets him apart is “the excellence of the music and its ability to express with immediate conviction the emotional states of the characters in the context of the drama.”

George Frideric Handel by Balthasar Denner

That particular assessment was enough endorsement for me, and I decided to get to know the Handel operas a little better. And what does an opera start with? An overture, of course. Overtures are instrumental pieces played before the start of the opera or one of its acts. In Handel’s time, audiences probably didn’t pay all that much attention to overtures. That’s just one more reason why we should take a closer listen to these musical gems. Here then are my 10 most exciting operatic overtures by Handel.

George Frideric Handel: Arminio, HWV 36 “Overture”

George Frideric Handel: Arminio, HWV 36 – Overture (Collegium Musicum 90; Simon Standage, cond.)

Johannes Gehrts: Arminio says goodbye to Thusnelda

Arminio first sounded at Covent Garden on 12 January 1737, and the opera is based on events of the Roman invasion of Germany in the year 9AD. In 1737, Handel’s opera company was fiercely competing against the Opera of the Nobility at the King’s Theatre in Haymarket. Both companies had insisted on performing on the same nights of the week, and that brilliant marketing strategy would soon misfire. Handel supporters liked Arminio very much, and a certain Mary Pendarves wrote, “I think it is as fine a one as any he has made.” A listener at the premiere wrote, “The overture is a very fine one, and the fugue I think as far as I can tell at once hearing not unlike to that in Admetus. The overture ends with a minuet strain.” The music journalist Charles Burney actually didn’t like the minuet in the overture very much, calling it “not very striking.” However, he found the opening “very beautiful, from the happy masterly use that is made from the contrary motion of the parts, and the fugue is written upon a curious subject in triple time, which none but a veteran in that kind of writing would have ventured to treat.” Sadly, Arminio was cancelled after six performances, and it was not heard again for another 200 years.

George Frideric Handel: Teseo, HWV 9 “Overture”

George Frideric Handel: Teseo, HWV 9 “Overture” (Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra; Nicholas McGegan, cond.)

Statue of Theseus in Athens

Teseo was first seen on stage on 10 January 1713, and the staging featured “flying dragons, transformation scenes, and apparitions.” It was a huge success with London audiences, even though the stage machinery for “the magical effects broke down, and the theatre manager ran away with the box office receipts.” The plot centers on the scheming enchantress Medea, who is haunted by her horrific actions of murdering her children and burning the city of Corinth. She longs for the salvation of love and uses her magical powers to force a union with “Teseo,” also known as Theseus. We end up with a love rectangle because King Egeo had first promised to marry Medea, but he changes his mind and plans to wed his ward, Agilea. Agilea, meanwhile, is in love with Teseo, and you can clearly see where this is heading. Handel relied on a five-act structure to musically tell the story, and the overture opens with a stately “Largo” with dotted rhythms and flourishes, characteristic of the French Overture. Instead of the expected fugal “Allegro,” Handel dives into an Italianate concerto before the “Largo” returns. “Instead of the customary minuet, Handel appends a concerto grosso movement, pitting a contrapuntal fugue for the trio of oboes and bassoon against a bustling flurry of strings.”

George Frideric Handel: Rodelinda, HWV 19 “Overture”

George Frideric Handel: Rodelinda, HWV 19 “Overture” (Welsh National Opera Orchestra; Richard Bonynge, cond.)

Francesca Cuzzoni

The plot of Rodelinda revolves around a dynastic dispute. Aripert, king of Lombardy, left his domains to his three children, Bertarido, Gundeberto and Eduige. Gundeberto sent his adviser Garibaldo to invite Grimoaldo, Duke of Benevento, to help him to get more than his share, in return for the hand of Eduige, now Queen of Pavia. In the ensuing war, Gundeberto was killed treacherously and Bertarido went missing, presumed dead, leaving behind his wife Rodelinda and their young son Flavio. Bertarido actually first appears halfway through Act I in disguise. The opera was a huge success, mainly because it starred the ideal pairing of the castrato Senesino and soprano Francesca Cuzzoni. Cuzzoni was described as “short and squat, with a doughy cross face, but fine complexion. She was not a good actress, dressed ill, and was silly and fantastical. And yet on her appearing in this opera, in a brown silk gown trimmed with silver, with the vulgarity and indecorum of which all the old ladies were much scandalised, the young adopted it as a fashion, so universally, that it seemed a national uniform for youth and beauty.” Handel provides the classic example of a Baroque overture, including the slow introduction and a fast contrapuntal allegro. Charles Burney writes that the overture in Rodelinda “long remained in favour because of the natural and pleasing minuet.”

George Frideric Handel: Serse, HWV 40 “Overture”

George Frideric Handel: Serse, HWV 40 “Overture” (Early Opera Company Orchestra; Christian Curnyn, cond.)

Serse

The opening aria about a tree “Ombra mai fù” would eventually become one of the best-loved Handel melodies. However, when Serse first sounded on 15 April 1738, it was not well received. Charles Burney wrote, “I have not been able to discover the author of the words of this drama: but it is one of the worst Handel ever set to Music: for besides feeble writing, there is a mixture of tragic-comedy and buffoonery in it, which Apostolo Zeno and Metastasio had banished from serious opera.” The semi-historical plot involves the hot-blooded Persian tyrant Xerxes. He is engaged to Amastre, who loves Romilda. Romilda loves Arsamene, Serse’s brother. Arsamene returns her love, but he is actually loved by Atalanta, Romilda’s sister. Throw in a bit of cross gendering, and the wheel of jealousy spins into comic relief. Following its disastrous premiere, the opera disappeared for almost two hundred years, with the first modern revival only taking place on 5 July 1924. Handel, it seems, had tried to be innovative in setting the drama. But his experimentation is already heard in the overture, which completely reverses the customary scheme. The fugal allegro actually sounds first and is then followed by the dotted rhythms of the French overture. And to crown it all, Handel presents a bouncing “Gigue” instead of the customary minuet.

George Frideric Handel: Orlando, HWV 31 “Overture”

George Frideric Handel: Orlando, HWV 31 “Overture” (Academy of Ancient Music; Christopher Hogwood, cond.)

Statue of Orlando in Bremen, Germany

The festive musical introduction for an opera, ballet, or suite during the Baroque is technically called a “French Overture.” It combines a slow opening in stately dotted rhythms that is commonly described as “majestic, heroic, festive and pompous.” It ends with a double bar and is repeated. The second segment is generally a lively fugal section, with entries sounding in rapid succession. With Handel, once a full texture has been reached, the music often becomes more homophonic or concertant. Once these two basic parts have been sounded, it is not unusual to find a brief return to the opening slow material giving way to an instrumental minuet. This additional music serves as a bridge between the overture proper and the first aria. Of course, things are not as rigid as they appear, as it is left to the composer’s imagination to test the boundaries of form and musical continuation. And Handel was certainly famous for his free and liberal approach to musical structure.

George Frideric Handel: Radamisto, HWV 12 “Overture”

George Frideric Handel: Radamisto, HWV 12 “Overture” (Freiburg Baroque Orchestra; Nicholas McGegan, cond.)

King George I

The Overture in Radamisto was a particular favorite of Charles Burney. He describes the first movement as “grand and Majestic” and the fugue as “superior to any that can be found in the overtures of other composers.” Later on, he hails the opera as “one of the most remarkable operas Handel ever produced.” Radamisto had been Handel’s first opera specifically written for the newly formed Royal Academy of Music. It seems that Handel held back the performance to mark an important social occasion. King George I and his son, the Prince of Wales, had not spoken for nearly three years. They reconciled on 23 April 1720, and Radamisto was put on stage four days later, with the monarchs appearing together in public. The opera was an immediate success, and Handel’s first biographer John Mainwaring noted, “Many ladies, who had forced their way into the house with an impetuosity ill-suited to their rank and sex, actually fainted through the excessive heat and closeness of it. Several gentlemen were turned back, who had offered forty shillings for a seat in the gallery, after having despaired of getting any in the pit or boxes.”

George Frideric Handel: Giulio Cesare in Egitto, HWV 17 “Overture”

George Frideric Handel: Giulio Cesare in Egitto, HWV 17 “Overture” (Bavarian State Orcehstra; Ivor Bolton, cond.)

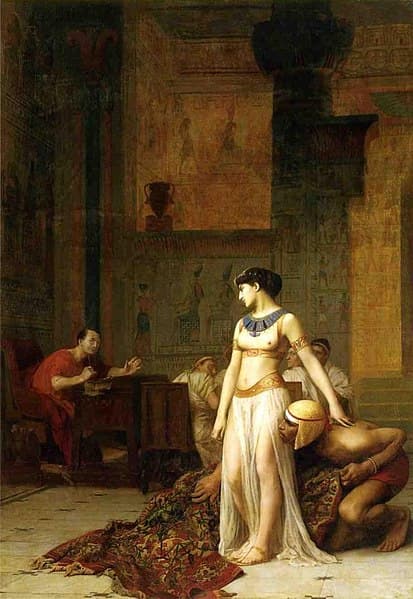

Cleopatra and Caesar by Jean-Leon-Gerome

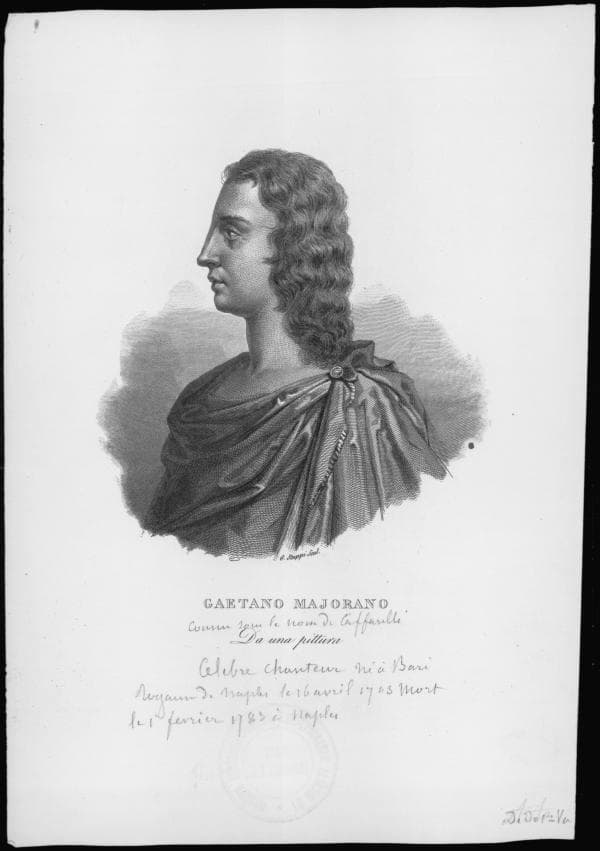

Handel decided to provide a decidedly lively overture for his opera Giulio Cesare in Egitto. Premiered in 1725 in London it was another showpiece for two of the greatest singers of the day, soprano Francesca Cuzzoni (Cleopatra), and alto castrato “Senesino” featuring as Julius Caesar. The plot, as you have guessed, comes from classical Roman history. It is a complicated version of Caesar’s conquest of Egypt and his fights with Pharaoh Tolomeo. And let’s not forget that Caesar falls in love with the Pharaoh’s daughter Cleopatra. Unlike the Shakespearean version, however, Marc Antony does not feature, and the opera comes to a happy conclusion. A critic writes, “this opera demonstrates the full flowering of Handel’s ability to blend perfectly text and music, create believable characters bodied forth in their arias, and create a fully-thought through dramatic arc.” Not everybody was hugely enthusiastic about Handel’s new aria, as the poet John Byrom wrote, “I sat in the front row of the gallery; it was the first entertainment of this nature that I ever saw, and will I hope to be the last, for of all the diversions of the town I least of all enter this one.”

George Frideric Handel: Tamerlano, HWV 18 “Overture”

George Frideric Handel: Tamerlano, HWV 18 “Overture” (Grande Écurie et la Chambre du Roy; Jean-Claude Malgoire, cond.)

Handel’s Tamerlano, title page of the libretto, London, 1724

“Timur the Lame” (Tamerlane) was a Turko-Mongol herdsman, probably a descendant of Genghis Khan. He established himself as a powerful ruler of what is now Uzbekistan, with a capital at Samarkand. His empire would eventually stretch from Delhi to Anatolia, and he defeated the Turkish sultan Bayezid I near Ankara in 1402. Contemporary chroniclers wrote accounts of the ruthless Tamerlane, who was said to have kept Bayezid in chains. It is told that Bayezid was transported in an iron cage and killed after imprisonment lasting eight months. Handel and his audience knew that story well, as Nicholas Rowe had turned it into a play in 1701. In this play, Tamerlane “represents virtue, whereas the volatile and irrational Bajazet represented vice and tyranny.” In Handel’s characterization, however, the roles are reversed on “account of the amount of sympathy one feels for the dying Bajazet after he has taken poison.” Handel also provides a glorious overture, with a minuet leading into the Sinfonia for the first Act.

George Frideric Handel: Agrippina, HWV 6 “Sinfonia”

George Frideric Handel: Agrippina, HWV 6 “Sinfonia” (Grande Écurie et la Chambre du Roy; Jean-Claude Malgoire, cond.)

Handel’s Agrippina title page

With his opera Agrippina, Handel created his first real masterpiece before moving to England. It is based on another classical Roman historical narrative, as the wife of emperor Claudius is determined to get her son Nerone on the throne, whatever the costs. The opera ran for twenty-seven performances during the carnival season in Venice, and essentially secured his international reputation. A scholar writes, “enthusiastic audiences greeted every pause in the music with cries of ‘Viva il caro Sassone’ (Long live the dear Saxon).” The music for Agrippina is a collection of pieces that Handel had written over the previous three years, and it blossoms with Handel’s famous self-borrowing. Interestingly, Handel called his overture “Sinfonia,” and for seemingly good reason. We do hear a nicely paced slow and dotted opening, but the fugal section quickly turns into a miniature concerto grosso that is frequently interrupted by highly dramatic gestures and pauses borrowed from dramatic rhetoric.

George Frideric Handel: Rinaldo, HWV 7 “Overture”

George Frideric Handel: Rinaldo, HWV 7 “Overture” (Capella Cracoviensis Orchestra; Jan Tomasz Adamus, cond.)

Rinaldo and Armida, 1629

Once in England, Handel introduced himself to London audiences with Rinaldo. In fact, it was the first original Italian opera ever to be performed on the London stage. London was eager for an “authentic Italian experience,” and the work caused a sensation with “it’s spectacular stage effects and costumes, and original music.” One scene grabbed all the headlines. As Almirena wonders in her garden towards the end of Act I, hundreds of real sparrows were released. Audiences were enchanted but one journalist wrote, “There have been so many birds let loose in this Opera, that it is feared the House will never get rid of them; and that in other Plays they may make their Entrance in very wrong and improper scenes…besides the Inconveniences which the Heads of the Audience may sometimes suffer from them.” Similar to the Sinfonia for Agrippina, the dotted opening is followed by a fugal section that transforms into a short concerto grosso in the Rinaldo overture. However, this time, the opening Largo returns and gives way to a very bouncy gigue. After listening to all of Handel’s 42 opera overtures, I can truly report that each one of them is infused with delightful musical charms, exceptional craftsmanship, and the composer’s famous idiosyncratic creativity.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter