Synesthesia is a fascinating neurological phenomenon in which the stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to involuntary experiences in another, unrelated pathway.

People with synesthesia are known as synesthetes. Synesthetes might perceive sensory information, such as colors, tastes, shapes, or even emotions, in response to stimuli that would normally only evoke one specific sensation.

© evolving-science.com

For example, a synesthete might see colors associated with specific letters or numbers, or experience tastes when hearing certain musical notes.

What color is Tuesday? Exploring synesthesia – Richard E. Cytowic

This blending of sensory perceptions results in a unique and often vividly interconnected sensory experience. Synesthesia offers us all a glimpse into the intricate ways in which the brain interprets the world around us.

As you can imagine, several famous composers from past and present generations have or have had synesthesia. Today we’re looking at some of the most famous examples…and what being a composer with synesthesia is really like.

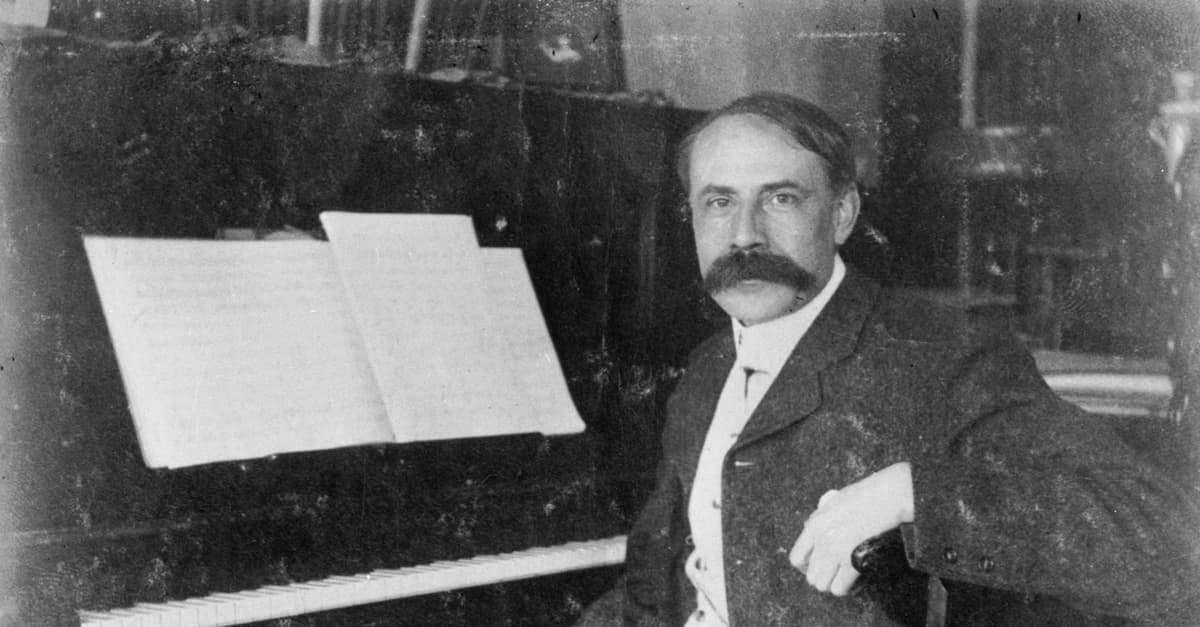

Jean Sibelius

Sibelius: Symphony No. 7

Finnish pianist Karl Ekman wrote about Jean Sibelius that he perceived “a strange, mysterious connection between sound and color, between the most secret perceptions of the eye and ear. Everything he saw produced a corresponding impression on his ear – every impression of sound was transferred and fixed as a color on the retina of his eye and thence to his memory.”

When he was young, whenever anyone would play the Sibelius family piano, Jean would associate different chords with the colors of the carpet piling.

Jean Sibelius

As an adult, he’d expand the metaphor from carpeting to mosaics: “Music for me is like a beautiful mosaic which God has put together. He takes all the pieces in his hand, throws them into the world, and we have to recreate the picture from the pieces.”

His visions had a specificity to them. He might hear a violin’s melodic line and interpret it as the color of a summer sunset.

Sibelius interpreted a C-major chord as red, a D-major chord as yellow, and an F-major chord as green.

His favorite combination? A yellowy light green. He once told his secretary, “It’s somewhere between D and E flat.”

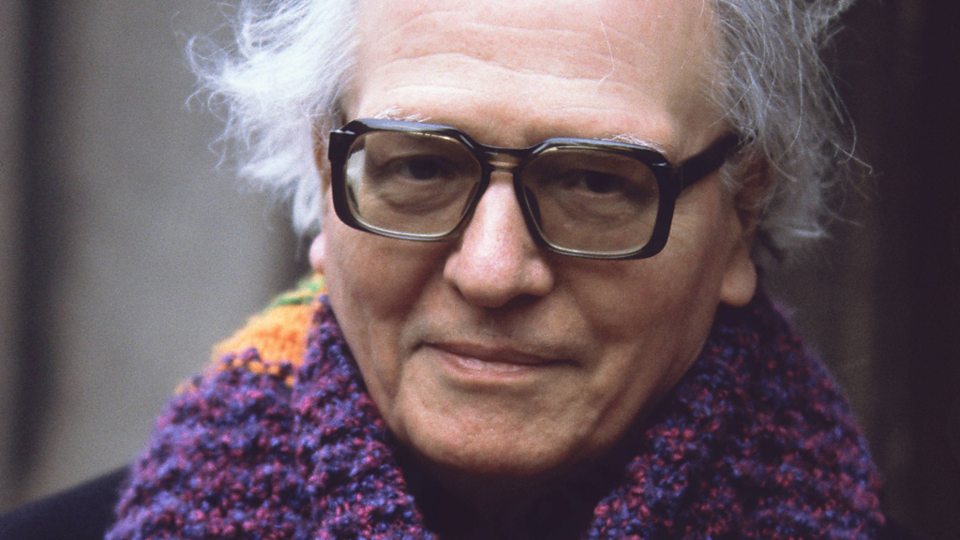

Olivier Messiaen

Messiaen: Couleurs de la Cité céleste

French composer Olivier Messiaen described his experience with synesthesia like this:

“I see colors when I hear sounds but I don’t see colors with my eyes. I see colors intellectually, in my head.”

Olivier Messiaen

Like Sibelius, Messiaen also had early experiences as a child that cemented the relationship between color and sound in his mind. When he was ten years old, he was dazzled by the stained glass at the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.

“What does a rose-window in a cathedral do?” he wrote of his 1963 work Couleurs de la cité céleste (“Colors of the Celestial City”) for piano, wind, and percussion. “It teaches through imagery, through symbolism, through all the characters that inhabit it – but what most catches the eye are its thousand spots of colour which ultimately dissolve into a single, very pure shade, so that someone looking on says only, ‘That window is blue’, or ‘That window is violet.’ I had nothing more than this in mind.”

What’s the Colour of Music? Messiaen and Colour

In the sheet music to Couleurs, certain chords are marked as “yellow topaz” and “bright green.” In his Quartet for the End of Time, he asked performers to create “blue-orange chords.”

One interesting quirk of Messiaen’s synesthesia was that if a chord was played an octave higher, he perceived it as paler, and if it was played an octave lower, he perceived it as darker.

Franz Liszt

Khatia Buniatishvili Plays Liebestraum No. 3 from Franz Liszt

There isn’t a huge amount of scholarship on Liszt’s synesthesia, but there is one famous anecdote that’s worth retelling.

When Liszt was serving as Kapellmeister in Weimar, while conducting his orchestra, he told the players, “Please, gentlemen, a little bluer! This tone type requires it!”

The players thought it was some kind of joke but after he kept saying it, they realized he was being serious.

Duke Ellington

Duke Ellington: Mood Indigo

Duke Ellington loved visual art and color so much that he almost became a painter. In his mid-teens, he received a scholarship to go to college to become an artist, but then he turned to pursuing music.

That shift in focus didn’t mean that visual art became less important to him. On the contrary, it became more important. His nephew wrote, “Given his synesthesia, it is not surprising that Duke referred to his band as his palette. He likened his stage performances to creating a new painting every night.”

JAZZIZ Essentials: Duke Ellington and Synesthesia

Interestingly, Ellington’s synesthesia was not necessarily connected to pitch, but rather character or texture of a pitch.

In 1958, he said in an interview: “I hear a note by one of the fellows in the band, and it’s one color. I hear the same note played by someone else and it’s a different color. When I hear sustained musical tones, I see colors in textures. If Harry Carney is playing, D is dark blue burlap. If Johnny Hodges is playing, G becomes light blue satin.”

This fascination with individual performers, as well as his synesthesia, played into Ellington’s prioritization of showcasing the individual talents of his colleagues.

Ramin Djawadi

‘Game of Thrones’ composer hears in colors

Ramin Djawadi is a composer of Iranian and German descent who was born in Germany in 1974. He is best known for his film scores. His most famous project to-date has been HBO’s Game of Thrones.

Ramin Djawadi

Djawadi’s wife, a television executive named Jennifer Hawks, once asked him how he wrote his music.

In an interview, he explained, “I said, well, I look at the pictures and I see blue and red and start painting, basically, adding notes and instrumentation. She looked it up and found out it was called synesthesia but I wasn’t aware until then that it was an actual thing. I always thought it was just normal.”

In another interview he said, “When I hear or write music, I just see colours which jump out at me. It’s not just a pure blue or pure red; it’s a combination of these and I layer them like a painting.”

Hans Zimmer

Hans Zimmer: Interstellar

Another film composer who has synesthesia is Hans Zimmer, famous for his soundtracks for The Lion King, the Pirates of the Caribbean movies, Inception, and others.

The Thin Red Line, a 1998 movie by filmmaker Terrence Malick, was a particularly unique experience. Malick asked Zimmer to write a soundtrack without having shot the film.

Hans Zimmer: The Thin Red Line (Journey to the line)

Zimmer recounted that experience in a later interview:

“I kept saying, ‘I need to see how you light this scene. I need to see how green the grass is in the valley you’re asking me to write about. On ‘The Lion King’, I had black-and-white drawings to work with, and I’m still kicking myself about one scene because I got the colour in the music wrong. I didn’t get the emotion right because the colours were clashing.”

Amy Beach

Amy Beach: Hermit Thrush at Morn, Op. 92

Composer Amy Beach, born in 1867 in New England, was one of the great American musical prodigies. She started composing waltzes at the age of four…in her head, without needing a piano!

Her mother used music as a disciplinary tactic: for example, if Amy misbehaved, her mother would play the piano in a minor key. This was deeply upsetting to her daughter.

Later, Beach once described what color came to mind when thinking about nine different keys. Seven were major keys; two were minor.

C Major White

E Major Yellow

G Major Red

A Major Green

A-flat Major Blue

D-flat Major Violet

E-flat Major Pink

G-sharp minor Black

F-sharp minor Black

Notice how the only two minor keys in that list are both black.

This intense relationship between color and key continued into adulthood. If a singer changed a Beach song to better suit their voice, it was intensely upsetting for Beach. She felt that to do so changed the intention and color of the song entirely.

What About Alexander Scriabin?

Nick Kanozik’s Light Organ (Clavière a lumiére) – Scriabin op 65 no 2

Scriabin is often cited as a composer who had synesthesia, but it’s uncertain that he really did, strictly speaking.

The reason? He didn’t actually perceive a color for a key when he heard it; rather, he preemptively assigned a color to each key based on the circle of fifths.

Scriabin came up with a whole theory about what color should be linked to what key. However, in contrast to Beach, he did not assign different colors to the major and minor modes of the same scale.

Alexander Scriabin

Even given all that, he’s still worth mentioning here just because of how important color was to his musical output. There are many examples of this, but the most relevant is probably his “Clavier à lumières”, a keyboard that he invented for use when performing his work Prometheus: The Poem of Fire. It cast colored lights into the space where an orchestra was playing, creating a kind of visual synesthesia for the audience.

Conclusion

For generations, composers with synesthesia have experienced intertwined relationships between chords, scales, and colors. And yet every human brain is different, and everyone with synesthesia “hears” different colors.

This phenomenon is truly fascinating – and also a very useful lens to use when studying and playing these composers’ works.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter